Editor’s Note: Looking back in time, people’s personal hygiene, fashion choices, medical treatments, and more sometimes look, at the very least, bizarre, if not outright disgusting. When confronted with these weird or gross practices, our first reaction can be to dismiss our ancestors as primitive, ignorant, or just silly. Before such judgments, however, we should try to understand the reasons behind these practices and recognize that our own descendants will judge some of what we do as strange or gross. Here at George Washington’s Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore, we’ve come to describe our efforts to understand the historically bizarre or disgusting as “Colonial Grossology.” The following is the latest installment in Lives & Legacies’ “Colonial Grossology” series.

The 100th rule of the famed Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior copied by George Washington as a school boy advised people to “Cleanse not your teeth with the Table Cloth Napkin Fork or Knife but if Others do it let it be done wt. a Pick Tooth.” This advice proved necessary two centuries ago because “the most common means of cleaning teeth was by rubbing them with a cloth dipped in a little salt and water.”[1] As long as this happened away from the dinner table, all would be well regarding propriety.

Dental care has improved greatly in 200 years but the seeds of modern tooth care can certainly be seen when looking back to colonial days.

Bristle toothbrushes are an age-old invention of the Chinese. Today’s brushes are remarkably similar in shape and design to ones used in centuries past. The pig bristle is now nylon and the animal bone is now plastic. Archaeologists have found bone toothbrush heads — two of which date from the 1820s — during excavations at Ferry Farm. Even without their handles, they look quite familiar even to the modern eye.

Instead of toothpaste, early Americans brushed with tooth powders. To clean teeth, these powders contained abrasives like alum, ground seashells, bone, eggshells, brimstone, baking soda, and even gunpowder. To freshen breath, powders included cinnamon, musk, or dragon’s blood.[2] If dragon’s blood sounds strange, tobacco merchant William Hugh Grove claimed tobacco ashes were “excellent to clean teeth!” These powders were not hard to make yourself and were even available for purchase in cities.

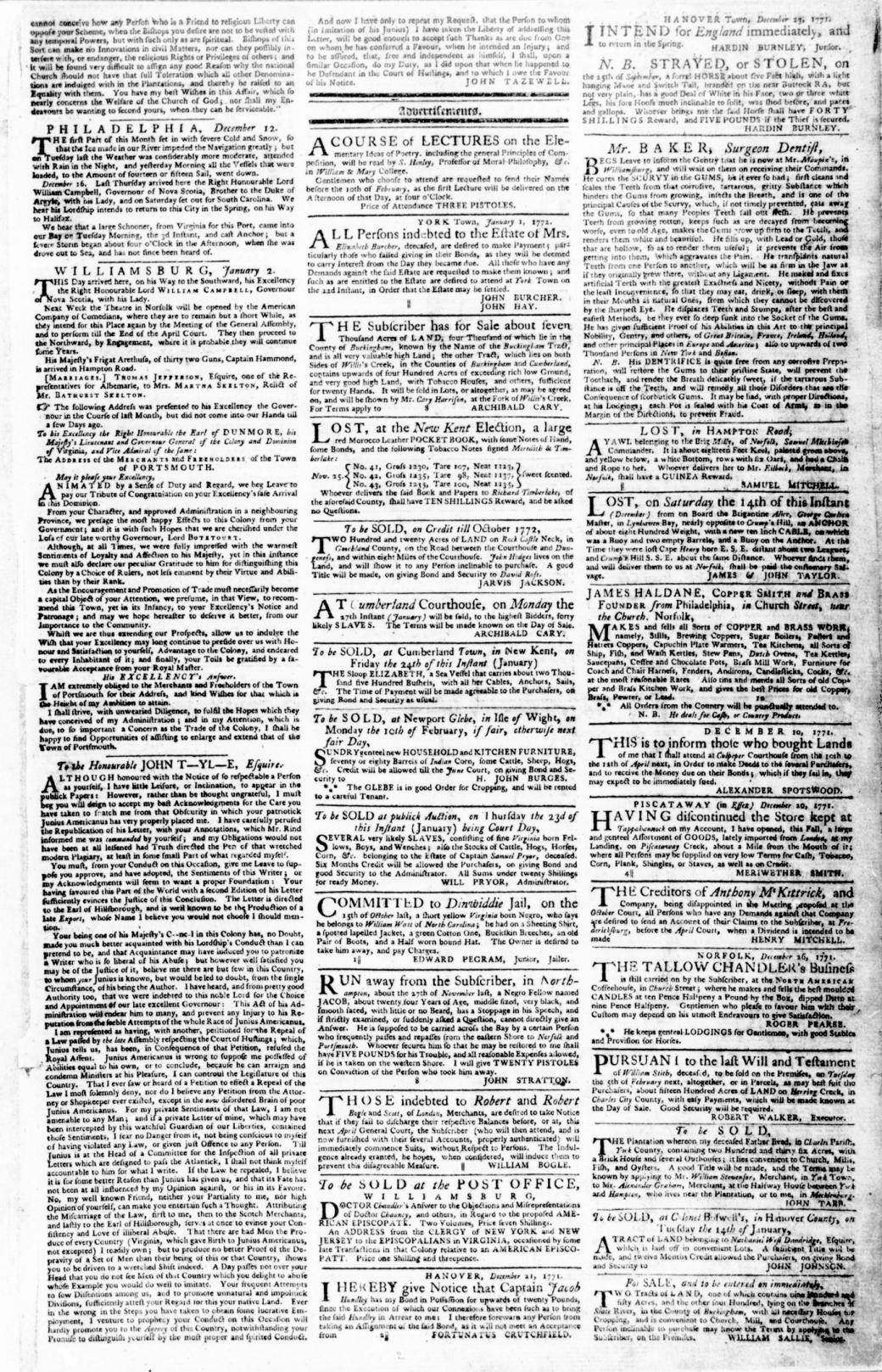

On January 2, 1772, ‘surgeon dentist’ John Baker took an ad in the Virginia Gazette “to inform the Gentry that he is now at Mr. Maupin’s, in Williamsburg, and will wait on them.” His ad is worth examining at length for its fascinating glimpse into dental procedures of the time.

Page 3 of the January 2, 1772 edition of The Virginia Gazette. Baker’s ad is near the top of the far right column.

Ostensibly, Baker could cure “the SCURVY in the GUMS, be it ever so bad.” He did so by scrapping from the teeth “that corrosive, tartarous, gritty Substance which hinders the Gums from growing, infects the Breath, and is one of the principal Causes of the Scurvy, which, if not timely prevented, eats away the Gums, so that many Peoples Teeth fall out fresh.” We each have essentially this same procedure performed every six months when we visit the dentist for a cleaning.

Furthermore, Baker said he “prevents Teeth from growing rotten, keeps such as are decayed from becoming worse, even to old Age, makes the Gums grow up firm to the Teeth, and renders them white and beautiful.”

In a passage familiar to any modern cavity suffers, the ad notes that Baker “fills up, with Lead or Gold, those that are hollow, so as to render them useful; it prevents the Air from getting into them, which aggravates the Pain.”

Baker even transplanted “natural Teeth from one Person to another.” The use of human teeth as replacements for extracted teeth as well as in dentures was quite common in the 1700s. Indeed, teeth collected from thousands of the dead after the Battle of Waterloo were used in dentures for years. Before Waterloo, “teeth were frequently acquired from executed criminals, exhumed bodies, dentists’ patients and even animals and were consequently often rotten, worn down or loaded with syphilis. The prospect of an overabundance of young, healthy teeth to be readily pillaged from the battlefield must have been a dentist’s dream.”

Surgeon Dentist Baker extracted whole or partial teeth, even if they were “ever so deep sunk into the Socket of the Gums.” Once extracted, the tooth was cleaned of infection and, if necessary, filled. Then, it might be placed back in the same person, into another person, or in a set of dentures. Some teeth even ended up in the archaeological record. An extracted human tooth was uncovered during excavations at Ferry Farm. From the upper jaw, the tooth belonged to a person of European descent and featured an incredibly large cavity. That said, the nerve was likely dead by the time this tooth was pulled. We know it was pulled because of a broken root. There is no decay from the top of the tooth and it has little wear, indicating it belonged to a younger person. The tooth was discovered in the plow zone[3], meaning that it could not be dated historically.

Using toothbrushes for preventative care, treating gum disease through cleaning, and filling cavities with lead or gold all represent some commonalities between past and present dental care. While seeds of modern dentistry can be traced to the 18th century, significant advances have been made in replacing single teeth and in using dentures. Even if past dentists had some of today’s treatments, however, it seems safe to bet that they still would have been unable to stop the terrible tooth trouble suffered by George Washington throughout his life. We now have picture of 18th century dentistry. In a future post, we’ll examine George’s famously troublesome teeth.

Zac Cunningham

Manager of Educational Programs

[1] Dorothy A. Mays, Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2004: 191.

[2] Dragon’s blood was a red powder obtain from any of several different plants and used as a folk medicine.

[3] The plow zone is the area of soil that is churned up during plowing. This churning destroys soil stratification or layering, which is the first method archaeologists use to date objects. This dating is based on the principle that the deeper an artifact is found in the soil, the older the artifact is. Plowing mixes up the artifacts and makes dating challenging.