Editor’s Note: Looking back in time, people’s personal hygiene, fashion choices, medical treatments, and more sometimes look, at the very least, bizarre, if not outright disgusting. When confronted with these weird or gross practices, our first reaction can be to dismiss our ancestors as primitive, ignorant, or just silly. Before such judgments, however, we should try to understand the reasons behind these practices and recognize that our own descendants will judge some of what we do as strange or gross. Here at George Washington’s Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore, we’ve come to describe our efforts to understand the historically bizarre or disgusting as “Colonial Grossology.” The following is the first in a series of “Colonial Grossology” posts that we’re offering on Lives & Legacies.

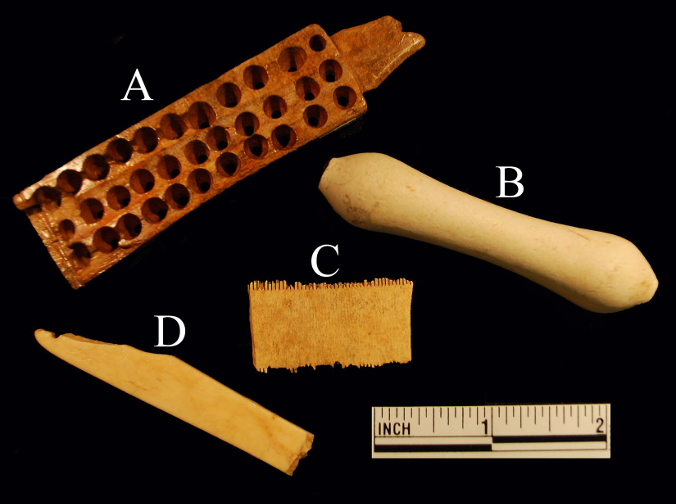

Archaeologists at George Washington’s Ferry Farm have recovered a variety of hair care artifacts, including over 200 wig hair curlers. These baked clay curlers were used exclusively to curl wig hair, and formed part of the Washington family’s regimen of wig maintenance. The regimen included several practices that might seem strange or gross to us today.

Artifacts from Ferry Farm related to eighteenth-century hair care. A) A woman’s bone hair brush, used on natural (not wig) hair. B) An earthenware wig hair curler, made c. 1740-1780. C) A bone grooming or “lice” comb. D) A bone razor guard, used by men to shave their facial hair and to shave the head to accommodate a tight-fitting wig.

Powdered wigs, or ‘perukes’, were highly fashionable among gentlemen of the 1700s, and a few affluent households even insisted that their butlers and coachmen wear them. Some gentlemen, including George Washington, opted not to wear a peruke. To remain fashionable these men often styled their own hair to resemble a wig.

![George Washington, 1796, by Gilbert Stuart [Public Domain]. His hair was pomaded and powdered by his personal valet.](https://livesandlegaciesblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/501px-gilbert_stuart_williamstown_portrait_of_george_washington.jpg?w=1040)

George Washington, 1796, by Gilbert Stuart [Public Domain]. His own hair, not a wig, was pomaded and powdered by his personal valet to look as if he were wearing a wig.

Throughout the 1700s, whether it was a person’s own hair or a peruke, pomade or pomatum was applied before wigs were powdered. The word ‘pomade’ derives from the Latin word for apple, “pomum,” – since early recipes incorporated apples. One recipe combined a pound of sheep suet (fat) with one pound of pig suet. Sixteen rosewater-boiled apples were added. Fragrance then enhanced this mixture, and might include some combination of rosewood oil, bay leaves, bergamot orange, or Macassar oil. Such fragrances helped to lengthen the interval between hairdressing sessions and counteracted any rancid odors.

Powder was typically made from wheat flour or dried white clay. Beanmeal or cornflour was also used. Powder was often enhanced by fragrances, such as those of orange flowers, rose petals, nutmeg, ambergris, jasmine, orris root, or lavender.

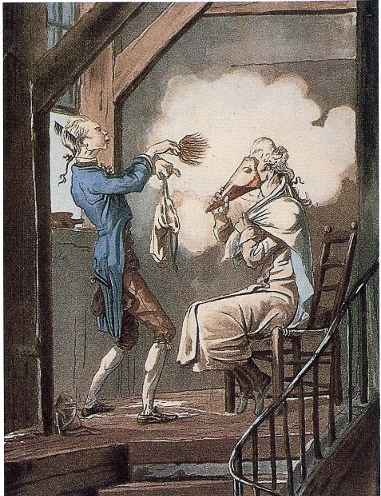

A hairdresser or personal valet added the powder, which was freshly applied every morning, or each time a wig was donned. The combination of lard and powder produced rigid curls and stiff hair styles. Powder made hairstyles heavier: as much as two pounds heavier for the large periwigs popular until the 1730s[1]. A few households featured ‘powder rooms:’ a small room set aside for the application of powder. A power bellows, a ‘carrot’[2], a swan-down puff, or comb was used to dust hair with powder. White or grey powders were especially popular, but adventurous consumers might use black, blue, lavender, pink, red, or yellow.

A gentleman being powdered by his valet. A cone protects the gentleman’s face during the process. Powder was made from starch, often wheat flour, or powdered white clay. The Toilette of the State Prosecutor’s Clerk, c. 1768 by Carle Vernet.

Hairdressers could remove wigs to apply pomade and powder in a separate space, a convenience for wig wearers that men who only wore their own hair likely envied. Men who did wear their own hair used a hairnet to preserve their pomaded locks overnight. Each morning[3], a valet combed out the previous day’s pomade and dirty powder, before applying fresh pomade and powder. This process could take an hour or more. Many hairstyles remained undisturbed for weeks. Headscratchers were kept close at hand: they allowed people to itch their scalps without disturbing their hairstyle too dramatically.

The beginnings of this fashion trend were inspired by disease and lice. Most people did not wash their hair very often. Syphilis was rampant in Europe throughout the colonial period. Symptoms such as hair loss, scabs, and rashes could be partially hidden beneath a voluminous wig. The prevalence of highly contagious head lice, and the difficulty in exterminating them, also encouraged the adoption of false hairpieces. In order to insure a good fit, gentleman shaved their heads, eliminating the hairs upon which lice thrived. While cleaning lice from one’s own hair could be time-consuming, wigs could be conveniently removed – and boiled to eliminate pests and dirt. However, if wigs were not properly maintained, they could become a haven for a variety of pests.To us today, the wearing of wigs covered in animal fat along with wheat flour or dried white clay may seem bizarre or disgusting or both. Still, to the people of the time the reasons behind the practices made perfect sense. Which of today’s perfectly sensible fashion choices might our descendants living 200 years in the future find strange or gross or both?

Laura Galke

Archaeologist, Site Director/Small Finds Analyst

[1] Periwigs took as many as ten heads of hair to produce.

[2] This was a carrot-shaped, wooden tube from which powder was blown onto the hair.

[3] Ideally fresh pomade and powder were freshened each morning. Frugal gentlemen might wait a week or more.