“The day being Rainy & Stormy – myself much disordered by a cold and inflammation in the left eye, I was prevented from visiting Lexington (where the first blood in the dispute with Great Britain) was drawn.” – George Washington, October 26, 1789

The sounds of sniffling, hacking, and sneezing, are everywhere, whether at a social events, shopping, or dining out. Here in the midst of our current cold and flu season, I thought readers might enjoy hearing about a historic, 1789-1790 respiratory malady that plagued many Americans and was referred to by contemporaries as “Washington’s influenza” or “the President’s Cough.[1]” So how did this widespread illness become associated with our first president? Read on!

In the fall of 1789 President Washington took advantage of a Congressional recess to embark on a tour of the nation over which he now presided. Capitalizing on his widespread popularity, Washington journeyed to diverse parts of the Atlantic states, in order to assess its industries, its potential, and to gauge the temperament of its diverse citizenry. In part an effort to validate the fragile new administration, Washington hoped the sojourn might demonstrate to Americans everywhere the promise of their new representative government: one in which all voters could participate.* The new administration was untested, and Washington realized its success could not be taken for granted. He appreciated that his own popularity would significantly contribute to its initial success and long term stability.

This particular trip focused upon the New England states. Everywhere that Washington traveled, he was greeted by throngs of enthusiastic well-wishers, and he quickly found crowds craved the opportunity to cheer their victorious general. Americans were especially exuberant when they witnessed the president, not in a suit (the attire of a politician), but rather in his splendid, buff-and-blue Revolutionary War general’s uniform. Washington exuded confidence in this familiar regalia, but his role as a political leader of a democratic republic was less familiar and did not ‘fit’ as well.

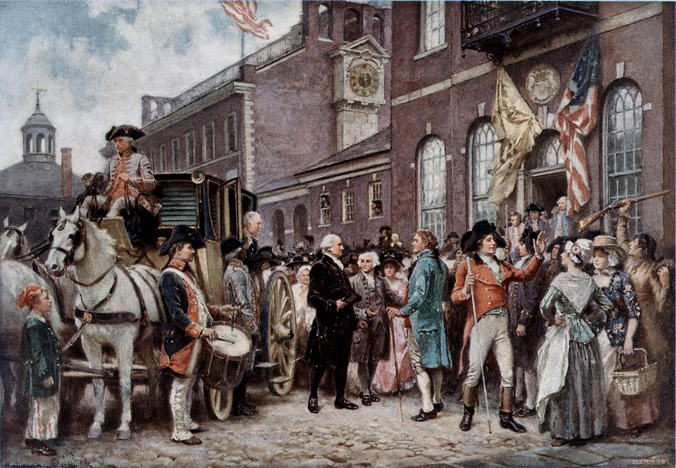

“Washington’s Inauguration at Philadelphia” by J.L.G. Ferris from a postcard published by The Foundation Press, Inc. in 1932, which itself was a reproduction of oil painting from the series: “The Pageant of a Nation.” This scene imagines George Washington arriving to be inaugurated at Congress Hall in Philadelphia on March 4, 1793. Credit: Library of Congress

From a young age, Washington was sensitive to the fact that his appropriate attire, deportment, expressions, and manners made good impressions that paved the way toward success. Elegant appearance and grace were personified by the self-conscious Washington, who first practiced these talents under his parent’s roof. Throughout this trip, if Washington was not in uniform, he often elected to wear black velvet mourning clothes, worn in honor of his late mother, who had recently passed away, losing her battle with breast cancer on August 25, 1789.

While Washington and the crowds who met him throughout his journey presented a stirring spectacle to the eye, the laudatory ceremonies were peppered by the sounds of wheezing and constant hacking from attending throngs and orators alike. The widespread disorder afflicting the new Americans originated in the southern states and Middle Atlantic region. In November, the American Mercury newspaper of Hartford, Connecticut reported that symptoms included “great languor, lowness, …anxiety, frequent sighing, sickness, and violent headache,” muscle aches and difficulty breathing (American Mercury November 9 1789:2). Children and the elderly appeared to escape the worst of the illness. The widespread illness was noted in letters and diaries across the nation. Newspapers recorded the spread of the pervasive illness.

Mere respiratory distress did not dissuade the hacking citizenry from catching a glimpse of their new president and showing their support for their republican government, however. Americans greeted Washington with pageantry and elaborate ceremonies. While well-intended, such rites made the first president – and many Americans – uncomfortable, as these formalities were too similar to the monarchical adulation from which the newly-established nation sought to distance itself. Adoring citizens cheers were interrupted by fits of coughing. Washington referred to it as an “epidemical cold.” The illness, sometimes referred to by contemporaries as an “epidemic catarrh”[2] proved fatal to a few of those so afflicted, which was especially vicious to those in the prime of life.

As he traveled, Washington maintained his correspondence. In a mid-October letter to his beloved – and only – sister Betty Lewis, George noted that he had thus far escaped falling victim to the highly contagious flu that gripped the nation. Two weeks after he wrote this letter, Washington admitted in his October 26 diary entry that he, too, suffered from the popular contagion. Despite the physical discomfort that his illness brought to him, Washington maintained his schedule, allowing each community through which his procession entered, to honor him with various events and dinners.

Despite the hardship of his illness, Washington’s exertions during his travels were an important contributor to the unification of a diverse assembly of states experimenting with democracy.

Laura Galke, Archaeologist

Small Finds Analyst

Further Reading

Breen, T. H.

2016 George Washington’s Journey: The President Forges a New Nation. Simon & Schuster, New York.

Twohig, Dorothy (editor)

1999 George Washington’s Diaries: An Abridgment. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville.

[1] Dorothy Twohig, editor, 1999 George Washington’s Diaries, An Abridgement, p. 351.

* Voting rights varied by state and were generally restricted to free men who owned land.

[2] American Mercury 9 November 1789:2, Pennsylvania Packet 18 November 1789:2