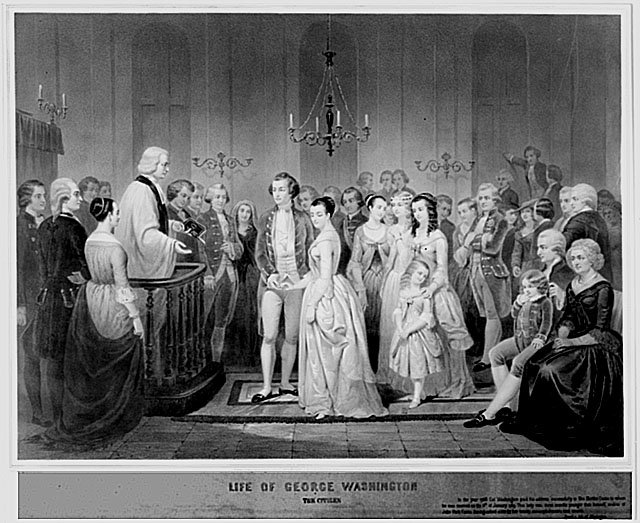

An imagining of the “Wedding of George Washington and Martha Custis.” Lithograph from Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. Paris: Lemercier, c1853.

A wedding is one of the most monumental moments in a person’s life. The celebrations that accompany the ceremony might range from simple to lavish but they are always highly anticipated and joyous. In this enthusiasm for weddings, we share much with our early American ancestors. Although there are extremely important differences between past and present, many wedding traditions of the 18th century would be quite familiar to 21st century Americans. What did a colonial-era wedding look like?

Today’s weddings can take place in any imaginable location – a church, dedicated wedding venue, cruise ship, beach resort, park, city hall, and on and on – but, in the 1700s, the large distances people often lived from an actual church building meant that the vast majority of weddings occurred at the brides’ home.[1]

In another inverse of modern preferences for spring, summer, and fall weddings, many colonial-era marriage celebrations took place in the winter months when there was less to do on the farm or plantation agriculturally.

That doesn’t mean there weren’t weddings outside the winter season. Indeed, Fielding and Betty married on May 7, 1750. We have no definitive evidence to say that their wedding occurred at the Washington family home on the land we now refer to as Ferry Farm. Since Fielding and Betty lived relatively close to St. George’s Church in Fredericksburg, it is certainly possible that the ceremony took place there, though it would have been fairly unusual.

If the ceremony did occur at the Washington home, an Anglican minister, perhaps from St. George’s, would have still read the marriage ceremony from the Book of Common Prayer. An edition published in 1750 contains language that remains immensely familiar even today.

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered together here in the sight of God, and in the face of this Congregation, to join together this Man and this Woman in holy Matrimony…”

“Wilt thou have this Man to thy wedded Husband, to live together after God’s Ordinance, in the holy Estate of Matrimony? Wilt thou obey him, serve him, love, honour and keep him in sickness and in health, and forsaking all other, keep thee only unto him, so long as ye both shall live?”

“With this Ring, I thee wed, with my body I thee worship, and with all my worldly goods I thee endow…”

Along with these familiar words came familiar acts as well. The father gave his daughter away, the couple exchanged vows, and the groom gave the bride a ring. The bride, however, did not present a ring to the groom.

Just as it does today, a party began after the ceremony. This celebration also took place at the home of the bride’s family. “The family might decorate a table with white paper chains and lay out white foods for a collation. It included two white cakes. The guests consumed the groom’s cake, and sometimes left the bride’s cake untouched for the couple to save (in a tin of alcohol) to eat on each wedding anniversary.”[2]

There was much food, drink, and toasting along with games and plenty of dancing. For Virginia’s gentry the party’s scale and length could be extremely lavish with the festivities continuing for days!

If you want to learn more about colonial-era weddings, you can witness a re-creation of the marriage ceremony of Fielding Lewis to Betty Washington on either Saturday, October 10 or Sunday, October 11 during Fielding’s Story: A Gentleman’s Sacrifice, a dramatic theater production taking place at both George Washington’s Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore. Fielding’s Story recounts important moments and milestones in Fielding’s life as a member of Virginia’s gentry, a wealthy merchant and leading citizen of Fredericksburg, the builder of Kenmore, a supporter of the American Revolution, and the husband of Betty. Reservations are required. Please call 540-340-0732 ext 24 or email hayes@gwffoundation.org.

[1] Jane Carson, Colonial Virginians at Play, Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1989: 5-9.

[2] Elizabeth Maurer, “Courtship and Marriage in the Eighteen Century,” http://www.history.org/history/teaching/enewsletter/volume7/mar09/courtship.cfm