The staff of Historic Kenmore & George Washington’s Ferry Farm regularly conducts research into the enslaved communities that existed at both Kenmore and Ferry Farm during the Lewis and Washington family occupations. Most of the surviving information about the enslaved is of a statistical nature – numbers, ages, locations, and luckily, names. In comparison to the amount of documentation surviving about the Lewis family at Kenmore, however, the records pertaining to that site’s enslaved residents are scant. And yet, Kenmore’s enslaved community is remarkably well-documented in comparison to other historic sites. At Kenmore, we started our project with four known primary documents which survive in our manuscript collection:

- “The Probate” – Fielding Lewis’s probate inventory, conducted in 1781

- “The Divvy List” – a list written by Betty Lewis, outlining the division of slaves between her children as directed by Fielding Lewis’s last will and testament (list is dated 1782 and provides the age of each enslaved person listed, as well as some familial relationships)

- “The Vendu List” – a page from an account book that lists the names of enslaved people, as well as the skill or trade for some, and some familial relationships, on the Kenmore property that are to be sold at vendu (public auction or sale) following Betty Lewis’s death in 1797 (list is dated 1798, the author is unknown)

- “The Final Disposition” – a similar page from an account book that lists the names of slaves who were actually sold at the vendu in 1798, as well as the price paid for each and in some cases, the person who purchased them (the author is unknown)

Initially, these documents provided us with a timeframe for slavery at Kenmore, and a way to calculate the number of people owned by the Lewis family (in total, we believe that Fielding Lewis owned approximately 132 people in 1781, spread between his two primary plantations in Fredericksburg and in Frederick County, Virginia). But, as we began to read the documents with a more critical eye, other details began to emerge – tiny notations and symbols, words crossed out by an unseen hand 200 years before, and abbreviations with an unknown meaning. We noted every single one of these pen strokes. There was actually a great deal of information hidden in plain sight on these documents – we just had to decipher it.

Portion of The Divvy List showing Abraham with an “R.W.” after his name.

One such mysterious notation appeared on the document we refer to as the Divvy List. One name, Abraham, appeared in the column for enslaved persons going to Robert Lewis. Abraham was listed as being age 25, and the letters “R.W.” were written after his name. What did R.W. mean? No other name in the document showed the same notation, and there didn’t appear to be any other clues in the Divvy List, so the mysterious “R.W.” was simply noted in Abraham’s file (we have developed a file for each enslaved person identified in the project) and we moved on. But Abraham’s odd notation would come up again, with some interesting significance.

In the Vendu List, we were presented with unambiguous, cut and dry information. Names of the enslaved, their skills, and children identified with their mothers. It didn’t require a great deal of interpretation. However, there were three enslaved people who showed some rather unusual skillsets. Bob, George, and Randolph were all listed as being “ropemakers.” While ropemaking was certainly an important trade in the 18th century, having three people with that skill in a group of 25 adults seemed somewhat unusual. Again, the information was noted in each individual’s file and we made a mental note to come back to it at some point.

Portion of The Divvy List showing Bob #2 with “Fredbg” after his name and Bob #2 with “Ropewalk” after his name.

The enslaved individual named Bob in the Vendu List was one of three Bobs who showed up throughout the four original primary documents, but only in the Divvy List did all three Bobs show up at the same time, which afforded us the chance to distinguish between the three individuals. Bob #1 was age 27, Bob #2 was age 50 and Bob #3 was 23 years of age. Bob #2 and #3 were listed as going to Lawrence Lewis, while Bob #1 was to stay with Betty. Using a device that she employed throughout the Divvy List to differentiate between people with the same name, Betty added a word after each Bob. Bob #1 had “(long)” written after his name, probably referring to a physical characteristic as “long” often meant “tall.” Bob #2 had “Fredbg” after his name. Obviously, this is simply an abbreviation for Fredericksburg where Bob lived (as opposed to the Lewis property in Frederick County). Bob #3 had “ropewalk” written after his name. Initially, we thought it was a misprint and that Betty had intended to write “ropemaker”, since one of the ropemakers on the Vendu List was a Bob. But, what if it wasn’t a misprint? What if, like “Fredbg”, “ropewalk” indicated the place where Bob 3 lived? And if that was the case, what if the notation of “R.W.” following Abraham’s name also indicated a place? What if that place was a “ropewalk”?

Prior to the invention of steam power, ropewalks were quite literally the places where rope was handmade throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. They were most often found in port cities, like Liverpool, England, Norfolk, Virginia, and Boston, Massachusetts (where the earliest colonial ropewalk is documented in 1642)[i], to serve the endless need of maritime vessels for incredible lengths of rope (the British Navy required that a single rope be no less than a 1,000 feet and the HMS Victory required 26 miles of rope).[ii] Once the American Revolution was in full swing, and the fledgling American Navy had come into existence, the colonies were on their own for producing enough cordage to supply the fleet, and smaller ropewalk operations began popping up in river towns and military supply centers.

Wright’s Rope Walk in Birmingham, England about the year 1770.

Large commercial ropewalks, like those in Boston, were comprised of low, one-story, incredibly long sheds (Gray’s Ropeworks in Boston was 934 feet long – more than 3 football fields), usually with only a roof. These structures housed a ditch in the ground, in which long hemp fibers were laid out and twisted together by “spinners” who had to walk the length of the building, backwards, while twisting and pulling hemp fibers, hence the name “walk.” A ropemaker could walk the equivalent of 20 miles in one day’s work.[iii] Spinners wore bundles of hemp fibers wrapped around their waists, which they fed into the twisting rope in front of them. Spaced at regular intervals along the ditch were wooden posts, with hooks mounted on them. The spinners would loop the freshly spun rope over the hooks as they proceeded down the ditch, to keep the tightly wound fibers from snapping backwards or coiling in on itself. Ropewalks were also known as incredibly dangerous places, as the air was filled with the fine dust of hemp fibers which easily ignited and could cause uncontrollable fire.

This back breaking work was done mostly by free tradespeople in northern cities. In fact, one of the first three men killed in the Boston Massacre was Samuel Gray, a ropemaker at Gray’s, who had been involved in several street fights with British soldiers, along with a gang of his fellow ropemakers, in the days leading up to the Massacre. Ropemakers were known agitators for the revolutionary cause and fomented sedition in the ropewalks of Boston.

In a complete contrast, in southern ports, ropemaking was performed almost entirely by enslaved labor. In Virginia, there were at least 18 ropewalks in operation by the end of the war. Three of them were government-sponsored and used public funds to purchase hemp from local farmers. The rest were private ventures, run by merchants and entrepreneurs who saw the growing need.[iv] The largest of the public operations was the Public Rope Walk in Warwick, near Richmond. It had become the primary rope producer for the Continental Navy after the British destruction of their own ropewalks at Norfolk, which had been confiscated by American forces after the war began.[v] At its height, Warwick employed 28 enslaved laborers. In 1781, Benedict Arnold led British forces against Richmond, with one of their main objectives being the destruction of the Warwick ropewalk, which they achieved. Fifteen of the enslaved workers were captured (or perhaps chose to leave with British forces). The Virginia government sold the remaining 13 ropemakers to private ropewalks around the colony.[vi] The catastrophe at Warwick was a huge blow to Virginia naval forces and for the duration of the war it was up to the smaller ropewalks to meet demand.

So, if Fielding Lewis owned enslaved persons who appeared to be living at or employed in a ropewalk, was there a ropewalk in Fredericksburg? Fredericksburg was a primary depot for supplies being shipped out to the Continental Army and to the Virginia militia. Fielding Lewis himself oversaw many supplies distributed out of Fredericksburg and, of course, he was one of the two owners of the Fredericksburg Gunnery, which manufactured and supplied weapons to the Continental Army. Additionally, Fielding owned several transatlantic trade ships, which he converted into naval patrol vessels once the war broke out. Those ships required rope before and during the war. Perhaps ropemaking was another war-time activity that Fielding participated in?

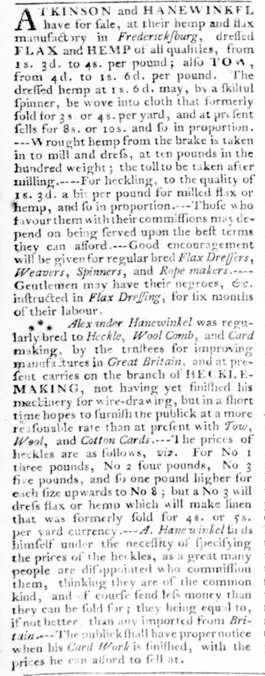

Advertisement for “dressed FLAX and HEMP” placed by John Atkinson and Alexander Hanewinkel in the September 6, 1776 edition of Purdie’s Virginia Gazette.

It turns out that there was indeed a local ropemaking industry with three separate ropewalks documented in the Fredericksburg area. According to an ad placed in the Virginia Gazette in September of 1776, Alexander Hanewinkel and John Atkinson had opened a hemp and flax factory that made textiles, sail cloth and rope, and included a school to train laborers to break and dress hemp for rope. It read, in part, “Gentlemen may have their negroes, etc. instructed in Flax Dressing, for six months of their labour.”[vii] However, it appears that Hanewinkel and Atkinson ran out of money for their venture by the end of the year and petitioned the House of Delegates to provide them funding. Hanewinkel and Atkinson specifically mentioned the high wages charged by laborers skilled in ropemaking and weaving as being among the reasons they were running short of money.[viii] Another ad in the Virginia Gazette in 1777 indicates that another ropewalk had been set up in nearby Falmouth by John Richards and James Long, who were seeking to hire a manager, but almost no record of this ropewalk exists beyond the ad.[ix] Lastly, John Frazer started the Fredericksburg Ropewalk, which appears to be the largest of all the local ventures. In fact, the Fredericksburg Ropewalk is documented as sending cordage north to supply the rope merchants in Alexandria, despite the presence of several ropewalks in that city.[x] Additionally, James Hunter (Fredericksburg merchant and business rival of Fielding Lewis) purchased 11,000 pounds of cordage from the Fredericksburg Ropewalk in 1779, indicating a rather large operation.[xi]

Likely because of the chaos of war and the ad hoc way in which the Americans were trying to supply the war effort, documentation for these ventures is hard to find, and therefore we don’t even know where in Fredericksburg the ropewalks were located. The smaller ropewalk operations begun to help the war effort were usually much less formal than their pre-war counterparts, like Gray’s Rope Works in Boston. Instead of actual sheds or roofed buildings, most were just the long, straight ditch in the ground, bordered by occasional wooden posts on either side, situated on flat stretches of land, like fields or flood plains. With so little actual structure, archaeological evidence for these sites is sparse. The Jones Point Ropewalk site in Alexandria, Virginia has been excavated, but archaeology revealed only post holes in long rows, with a stained stretch of ground between them (the stain may have been caused by the tar that was poured over the rope to make it resistant to rot).[xii] Such a site would be hard to locate without any indication of where to look.

The Fredericksburg Ropewalk probably did not have actual sheds or roofed buildings. It was most likely just a long, straight ditch in the ground, bordered by occasional wooden posts on either side, situated on a flat stretch of land similar to this Dutch ropewalk.

The likeliest candidates for the places where the Lewis family’s enslaved ropewalkers Abraham, Bob, George and Randolph were employed are either the Hanewinkel & Atkinson factory and school, where Fielding might have sent them to learn a profitable (for him) trade, or the Fredericksburg Ropewalk, which was clearly the largest operation in the area. But, the petition for funds put before the House of Delegates by Hanewinkel seems to indicate that he and his business partner were having no luck in attracting owners to provide slave labor to their ropewalk. On the other hand, would Fielding have been willing to supply labor at his own expense to business rivals like James Hunter and John Fraser?

Interestingly, it may be that a major clue about enslaved ropemakers at Kenmore was right in front of us all along. Among the “odds and ends” of assets and instructions for their disposition listed at the very end of Fielding Lewis’s will is “my share in the Chatham rope walk in Richmond” (which Fielding directs to be sold and the proceeds divided between his sons). Prior to learning that three, and possibly four, of the enslaved persons at Kenmore were ropemakers, this reference seemed to be just one of many rather insignificant business matters. But suddenly it became a more important notation. What was the Chatham ropewalk? Obviously it was in Richmond, but could we learn anything more about it? In fact, we could.

The Chatham ropewalk (sometimes called the Chatham Rope Company, sometimes the Chatham Rope Yard, and also the Chatham Ropery) was owned by a consortium of businessmen led by Archibald Cary, who also had part ownership in one of the ropewalks destroyed by the British at Norfolk in 1776.[xiii] It didn’t take him long to regroup however, and less than a year later, in August 1777, Cary and associates were advertising in the Virginia Gazette for trained spinners to work at the Chatham site, which was located on Shockoe Hill. Fielding Lewis is not mentioned as one of the founding investors in the venture, but he certainly knew Cary, as they served in the House of Burgesses together and both were tasked with procuring military supplies in central Virginia.

Rope, or line, was an 18th century essential, rather on Atlantic sailing vessels or a Virginia farm.

There appears to be some debate about the fate of the Chatham ropewalk. In January of 1781, when Benedict Arnold and his British forces raided Richmond, many industrial buildings were intentionally destroyed, aimed at critically injuring the American war machine. Arnold identified a ropewalk as being among the facilities that he and his men destroyed in Richmond (in addition to the ropewalk at Warwick, outside of Richmond), and since most of their destruction took place in and around Shockoe Hill, some historians maintain that the Chatham ropewalk seems the likely candidate.[xiv] However, the Marquis de Lafayette apparently quartered his troops inside the ropewalk “on the east side of the city”[xv] (which would also describe the location of the Chatham ropewalk) when they marched through Richmond a few months later, which would seem to indicate that the ropewalk structure was still standing. And of course, Fielding Lewis seemed to feel that his share in the Chatham ropewalk was still worth something when he wrote his will in October of 1781. No additional family documents shed any light on whether or not the share was sold as directed.

So, the question now becomes, did Fielding Lewis send Abraham, Bob, George, and Randolph to work and possibly live at the local Fredericksburg ropewalks or did he send them all the way to Richmond to work and live at a ropewalk in which he had a financial stake? Arguments for both can be made, but at the moment we haven’t found any documentation to conclusively say which it was. One final clue, although its meaning is still unclear, was discovered in a fragmented receipt in the Kenmore archival collection. The receipt, dated 1794, shows that Betty Lewis paid off her account with the Fredericksburg general mercantile store Callender & Henderson by hiring out the labor of Bob, George, and Randolph for one year to David Henderson.[xvi] As all three were ropemakers, we have to assume that Henderson was interested in them for that skill and was aware that they had it.

As to the ultimate fates of Abraham, Bob, Randolph, and George, we know some things. Abraham was intended to go to Robert Lewis when he came of age, and so we assume that he did. However, estate records for Robert Lewis show no Abraham on his property at the time of Robert’s death. Bob was apparently intended to go to Lawrence Lewis, but instead he must have stayed with Betty Lewis, as his name and occupation of ropemaker appear on the Vendu List in 1797. However, his name does not appear on the Final Disposition, so we do not know with any certainty who purchased him at the sale. Randolph also stayed at Kenmore and is listed on the Final Disposition document as being sold to George Lewis for £121. As property of George Lewis, he would have gone to Marmion Plantation on the Northern Neck. Interestingly, George was also sold to George Lewis in the Final Disposition, for £122, meaning that Lewis had purchased two of the three ropemakers listed.

Abraham’s mysterious “R.W.” notation was initially just a fragment of information to be cataloged as part of the larger project to research the enslaved communities at both Kenmore and Ferry Farm. While we know almost nothing else of this man, that tiny two-letter notation revealed a story that he was a large part of – what trade he may have had, where he may have lived, and which members of his community he may have been closest to. We will continue to search for these larger stories in the smallest of details.

Meghan Budinger

Aldrich Director of Curatorial Operations

[i] Samuel Gray. Boston Massacre Historical Society. http://www.bostonmassacre.net

[ii] HMS Victory, The National Museum of the Royal Navy. https://web.archive.org/web/20120501012634/http://www.hms-victory.com

[iii] The Long Story of the Jones Point Ropewalk, 1833 – 1850. National Park Service Historical Marker. https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=127774

[iv] Swenson, Ben. Hemp & Flax in Colonial America. Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Winter 2015.

[v] Ward, Harry M. and Harold E. Greer, Jr. Richmond During the Revolution: 1775 – 1783. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. Pg. 136.

[vi] Herndon, G. Melvin. A War-Inspired Industry: The Manufacture of Hemp in Virginia During the Revolution. The Virginia Magazine of History & Biography, Vol. 74, No.3 (July, 1966). Pg. 309.

[vii] Ibid, Pg. 305. Virginia Gazette, September 5, 1776.

[viii] Journal of the House of Delegates, Anno Domini 1776. Library of Virginia. Pg. 8.

[ix] Herndon, 307. Virginia Gazette, June 6, 1777.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] John Frazer to James Hunter, August 25, 1782. ALS. Hunter Family Papers, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, VA.

[xii] The Long Story of the Jones Point Ropewalk, 1833 – 1850.

[xiii] Ward, 136.

[xiv] Ibid, 137.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Receipt, January – December, 1794. Kenmore Manuscript Collection, MS 716.