Once again this summer, Historic Kenmore looks forward to its annual Shakespeare on the Lawn performances. While settings and costumes may change, today’s Shakespeare audiences most usually witness performances that remain true to the artistry of an unchallenged master carefully crafting his words and stories for the Elizabethan age. Two centuries ago, however, colonial-era theatregoers like George Washington (who loved attending the theater and did so right here in Fredericksburg) and Fielding Lewis often witnessed drastically altered versions of the Bard’s famous works.

Today, William Shakespeare’s King Lear is celebrated as his greatest tragedy; some may even argue one of the greatest theatrical tragedies ever. This June, Kenmore’s audiences will see Shakespeare’s tragic version, which is far different from the version Washington or Lewis may have witnessed. Indeed, in times past, Shakespeare’s Lear was not always a tragedy. In this two-part post, we’ll review the history of the Lear story and discuss how that story changed to please audiences of different eras.

King Lear was not a random literary invention of William Shakespeare. In fact, his Lear was not even the first character of that name to tread the board of an English stage. The name and story of King Lear (or Leir in the earlier iterations) come to us originally from Geoffrey Monmouth’s Latin manuscript Historia Regum Britanniae [“History of the Kings of Britain”] written c. 1136. Monmouth actually introduces two kings that Shakespeare would dramatize in his writings: Cymbeline and Leir.

Monmouth’s Leir is a king of 8th Century BCE Brittany and is assumed to be more myth than man. Still, the story is a familiar one. It tells of a king who divides his land between his three daughters. To decide who gets the largest portion, Leir asks who loves him the most. The two elder daughters, Gonorilla and Ragau, lie and flatter their father but the youngest and only true daughter, Cordeilla, answers humbly. Leir banishes his youngest child. He is then betrayed, usurped, and banished by Gonorilla and Ragau. Now united, Cordeilla and Leir rally an army, restore him to the throne, and survive the ordeal. This is the story known to English history and folklore long before Shakespeare’s time.

But is this the account that inspires Shakespeare? Honestly, it is difficult to say. In the Elizabethan age, Historia Regum Britanniae had not yet been translated from Latin. Shakespeare undoubtedly took Latin lessons in his youth and perhaps he was exposed to Monmouth’s stories in these lessons.

There are, however, two other works from Shakespeare’s own time that are more likely to have inspired his classic tragedy: Holinshed’s history book The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland and a play called The Chronicle History of King Leir.

Holinshed’s Chronicles is a collection of stories from British history originally published in 1577 and then again in 1587. It included two stories that Shakespeare dramatized. One was the story of a somewhat forgotten Scottish king named Macbeth while the other was the story of King Leir.

The play The Chronicle History of King Leir about a father and his three daughters clearly took its story of Leir from Holinshed’s Chronicles. It was performed at the Rose Theatre in 1594. Shakespeare clearly knew this play since it features similar passages to some of his own scenes. Yet, this earlier play is still missing some of the key elements for which Shakespeare’s is known. There is no fool, the subplot between Gloucester and his sons is absent, and, most notably, Leir and Cordelia survive. These elements are the inventions of the Bard. What inspired him to change this tragicomedy into his greatest tragedy?

Title page for M. William Shake-speare, his true chronicle historie of the life and death of King Lear, and his three daughters, 1608, by William Shakespeare

The state of English society and its monarchy when Shakespeare wrote King Lear is key to understanding this shift. The only known performance of Shakespeare’s version in the Bard’s lifetime was for King James I on St. Stephen’s Day in 1606. Only three years earlier, James’ accession united England and Scotland into one kingdom. Such a shift in power, even a peaceful one, caused a rise in tension among Britons. These tensions were especially high following the Gunpowder Plot, when Catholics attempted to assassinate the Protestant James by blowing up Parliament the previous year.

Like art from any era, Shakespeare took his cues from the fears of the populous. His play came out in an England nervous about its future. The last monarch died without a direct heir. Some questioned the current monarch’s claim. Fears of faction and civil war were in abundance.

Shakespeare’s tale about a king who divides his kingdom reflected the fears of the people of England and had a very tangible correlation to their own lives. Shakespeare’s King Lear is a cautionary tale about a divided kingdom; it is an example of everything terrible that can come from a nation dividing itself. This is why Shakespeare allows a fool to cast doubt on the king’s decisions, allows a monarch to go mad, and allows an ending that is full of tragedy without hope.

This Elizabethan version is the King Lear known to most modern theatregoers and it comes right out of Shakespeare’s world. Just as Elizabethan audiences expected the play to reflect their times, however, later 18th century audiences also wanted a King Lear unique to their time and tastes. In part two, we’ll see how the English Civil War and the Restoration changed this story once again as King Lear comes to the America of George Washington and Fielding Lewis.

Joe Ziarko

Manager of Interpretation and Visitor Services

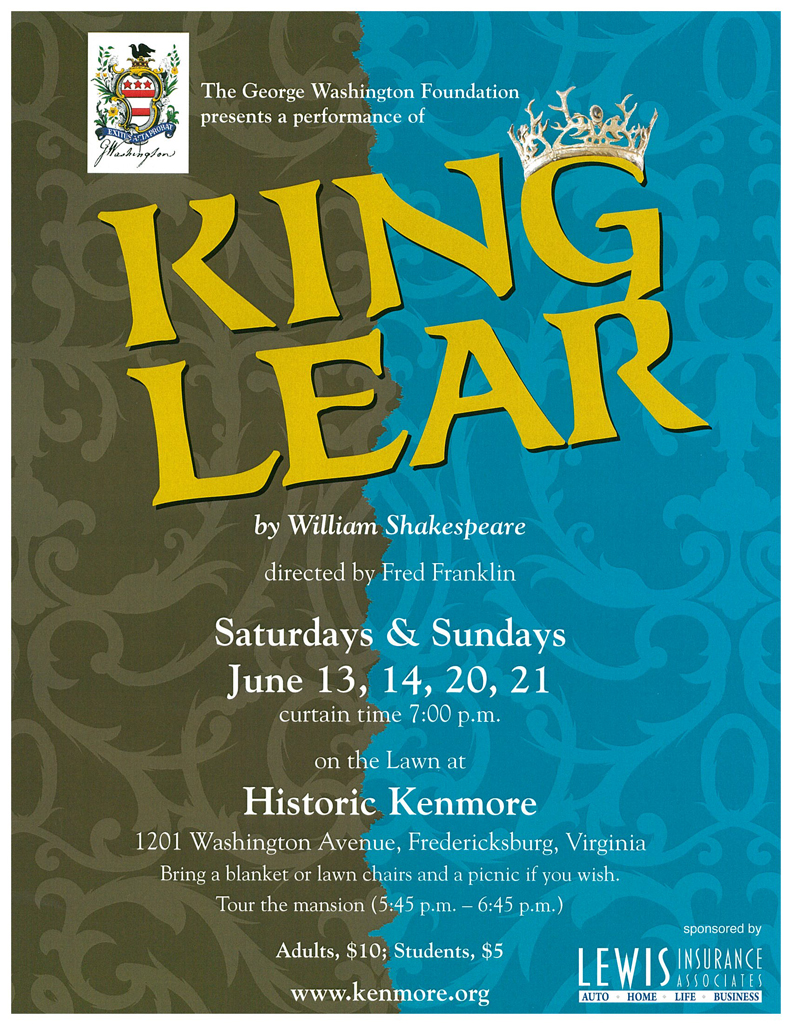

See Shakespeare’s King Lear during Historic Kenmore’s Shakespeare on the Lawn. For details, check below or visit http://kenmore.org/events.html.