What do you get when you have a canoe, tools, and a dream team of builders? The Great Oak Pavilion! Okay, maybe the canoe wasn’t completely necessary, but it is a very interesting part of the construction of the Great Oak Pavilion. Many visitors at Ferry Farm have questions about this building and how it came to be. Did George Washington build it? How did it get here? And what is it all about?

For starters, contrary to popular belief (mostly by our younger visitors), George Washington did not build the Pavilion. Construction on the building began in 2005 through a collaborative effort of the Virginia Military Institute, Timber Framers Guild, and the George Washington Foundation, who together built a much-needed classroom space for the foundation. How, you might ask, did these forces come together? It just so happened that longtime foundation supporter Dr. Grigg Mullen was also a member of the Timber Framers Guild and a professor of Civil Engineering at VMI. Together with Matt Webster, the GWF Director of Architectural Restoration, Dr. Mullen and the team designed the Great Oak Pavilion. He even had his students help construct the building over their spring break!

While it wasn’t built in the 18th century, many of the pavilion’s construction techniques reflect those that would have been used during that period. These techniques allow the pavilion to fit seamlessly within the landscape. As a self-proclaimed architecture nerd, I can’t just leave it at that, so let’s go over a few building techniques. Next time you visit, see if you can spot them!

One of the major things you may notice is that no nails or metal plates are used in constructing the building’s frame. In fact, nails are only used to attach the wooden shingles and siding, just as it would have been done in the colonial period. Instead, the timbers are connected using traditional joinery techniques, where each piece of wood is cut in a specific way so that the pieces fit snuggly together – sort of like a puzzle piece. The “puzzle pieces” can be very elaborate or simple, it all depends on the function of the joint.

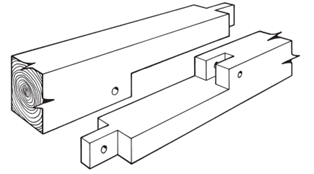

Mortise and tenon joints are commonly used joints throughout the Pavilion. They are created by cutting a slot (mortise) in one timber and then reducing the wood on another timber to create a tab (tenon). The tenon fits into the mortise to create a strong, stable compression joint.

Another type of joint, the halved and bridled scarf joint, is also used in the Pavilion. These connect timbers, increasing the length of a beam. Notches are cut into the beams in this joint, which then fit inside the overlapping timbers. Wooden pins provide extra security.

The 18th-century techniques don’t stop there! The design of the Pavilion is modeled after Kenmore, using the same support system for the roof. The construction of the 2005 truss system, known as a king post truss, is the same system used at Kenmore when it was built in the early 1770s.

Now, don’t think I forgot about the canoe part of the story. Remember how I mentioned the construction occurred over spring break? Well, it just so happened to be a very rainy spring. So rainy in fact, that the area where the builders were working and camping for the week flooded. That didn’t stop them, though. They just loaded up their wares in a canoe and paddled back and forth to the site. That’s dedication!

While the Great Oak Pavilion may not have been built by George Washington, it demonstrates how the George Washington Foundation and its supporters can come together to make great things happen. In other words, teamwork does indeed make the dream work.

Danielle Arens

GWF Archaeologist

References

National Park Service (2001). Historic American Timber Joinery A Graphic Guide.