“I heard Bulletts whistle and believe me there was something charming in the sound.”[1] — George Washington

Before his first brush with battle, three military adventures worked together to charm and inspire young George Washington’s fascination with the military and helped push him to pursue a career as a soldier in Virginia’s militia and then as commander of the Continental Army.

Portrait of Lawrence Washington attributed to Gustavus Hesselius (c. 1738). Credit: Wikipedia / Mount Vernon.

The boy Washington was first charmed by the military service of his older half-brother Lawrence. In 1739, the colorfully-named War of Jenkins’ Ear between Britain and Spain began. Ostensibly sparked by the Spanish coast guard boarding a ship captained by Robert Jenkins and cutting off his ear, the war was another one of those conflicts over trade, colonies, and the spoils of the New World so often fought between Europe’s empires in the 18th century.

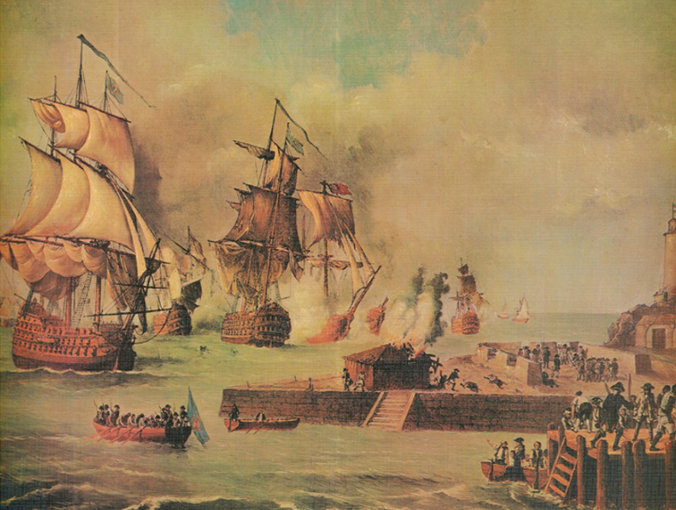

In June 1740, a commission from George II arrived in Virginia for Lawrence. He was made a captain in one of four infantry regiments of colonial Virginians being raised for service in the war. On May 30, 1741, Lawrence wrote to his father Augustine describing his role in the Battle of Cartegena de Indias when the British launched an amphibious assault on the city of Cartegena de Indias in Colombia.

Lawrence reported to his father that the British “destroyed eight Forts, six Men of War, six gallioons and some Merchant ships” but “what number of Men they [the Spaniards] lost we know not; the enemy killed of ours about six hundred & some wounded, & the climate killed us in greated [sic] numbers.” In the end, the British suffered a crushing defeat but more because of disease than battle casualties.

“Defensa de Cartagena de Indias por la escuadra de D. Blas de Lezo, año 1741” by Luis Fernández Gordillo. Credit: Wikipedia / Naval Museum of Madrid.

Virginia’s regiments suffered greatly. “Some are so weak as to be reduced to a third of their men,” Lawrence wrote but he also revealed that “vastly to my satisfaction” he had been serving “on board Admiral Vernon’s ship.” Vernon was the naval commander during the battle and was greatly admired by Lawrence. He was so admired, in fact, that Lawrence named the family’s Little Hunting Creek property bequeathed to him after Augustine’s death Mount Vernon.

Portrait of Edward Vernon by Thomas Gainsborough, c. 1753 (NPG 881). Credit: National Portrait Gallery, London.

Lawrence ultimately concluded that “war is horrid in fact, but much more so in imagination.” His experiences aboard an admiral’s flagship probably protected him some from the horrors of war. War did not turn Lawrence off of military service. He was awarded the post of Adjutant General for all of Northern Virginia’s militia along with the rank of major.

George was about 10-years-old when Lawrence returned home from war. How many war stories did his older brother share with him? We do not know but we do know that George and Lawrence were close, especially in the aftermath of their father’s death. It seems a safe bet to conclude that Lawrence’s military service also likely influenced his effort in 1746 to have fourteen-year-old George join the Royal Navy.

George’s captivation with military adventure was further strengthened by the exploits of Duke Frederick Herman von Schomberg. On September 10, 1747, fourteen-year-old George purchased 3 books from his cousin Bailey for the combined price of 4 shillings 12 pence. One of the books is listed as “Scomberg,” a reference to a 17th century German Protestant soldier of fortune, who fought under the flags of France, Germany, Portugal, and England and died at the Battle of the Boyne fighting for William of Orange. Schomberg wrote about his adventures, which would have been of great interest to a young man like Washington. That George willing spent hard earned money during a time of financial hardship reveals how enthralled he was with military exploits.

Portrait of Friedrich von Schomberg atrributed to Adrian van der Werff (c. 1600s) Credit: Wikipedia.

We do not know the impact, if any, of Schomberg’s exploits upon George’s military thinking. One incident does stands out, however. While in Ireland commanding the army of William of Orange, England’s new king, against supporters of James II, England’s old king, Schomberg decided that his raw and undisciplined troops would not fare well in battle. As a result, he held his army behind defensive works instead of confronting the enemy and their superior numbers. This much-criticized action bares notable similarities to Washington’s main strategy during the Revolutionary War. Washington defeated the British because, overall, he did not fight the British. Instead, he maintained his “army in being.” Washington wisely avoided confrontation, when possible, with the professionals who made up the best army in the world. The American army was inexperienced and initially amateur but as long as the army existed, the newly independent United States would also exist. The Continental Army had to survive even if that meant avoiding, instead of confronting, the British Army.

The final adventure that inspired a fascination with military things in young George Washington was his trip to Barbados. In 1751, nineteen-year-old George and his older half-brother Lawrence traveled to that Caribbean island in the hope that the tropical climate would relieve Lawrence’s tuberculous. This was George’s first and only trip away from the North American continent and to another part in Britain’s vast Empire.

Early in their stay, Washington made the first of several visits to Needham’s Fort guarding the south side of Carlisle Bay. He met Captain Petrie, the fort’s commander, and dined with him at the fort more then once. The fortress seems to have impressed the teenage Washington for he recorded in his journal that it was “pretty strongly fortified and mounts about 36 Gunes within the fortifin and 2 facine Batterys.”[2]

Needham’s Point, Barbados. Credit: Reinhard Link.

Furthermore, he and Lawrence stayed at the house of Captain Croftan, who commanded James Fort on the bay’s north side. Even Croftan’s house, Washington noted, “command[ed] the prospect of Carlyle Bay & all the shipping in such manner that none can go in or out with out being open to our view.”[3]

Home of Captain Croftan where Washington lived during the several months he visited Barbados in 1751. Credit: Wikipedia / Jerry E. and Roy Klotz

On the return voyage to Virginia and Ferry Farm, George judged that because Barbados had “large intrenchments cast up wherever its possible for an Enemy to Land” the island itself was essentially “one intire fortification.”[4]

As Jack Warren ably concludes, “George Washington’s encounter with the British military establishment in Barbados seems to have had a crucial impact on his aspirations . . . . After returning to Virginia, he dedicated himself to advancement in the military more completely than any of his Virginia contemporaries. And unlike most of the prominent colonial militia officers of the 1750s, he sought a commission in the regular British military establishment– an ambition that was probably prompted, and undoubtedly stimulated, by his experience in Barbados.”

Portrait of George Washington (1772) by Charles Willson Peale. The earliest authenticated portrait depicts Washington in the Virginia Militia uniform he wore during the French and Indian War. Credit: Washington and Lee University / Wikipedia

These three military adventures – Lawrence’s service in the War of Jenkin’s Ear, the written exploits of Schomberg, and George’s trip to the heavily fortified imperial outpost of Barbados – all worked to inspire Washington’s fascination with military matters and drove him to eventually pursue the life of a soldier in the French and Indian War and then, most importantly, in the War for Independence.

Zac Cunningham

Manager of Educational Programs

[1] George Washington to John Augustine Washington, May 31, 1754, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-01-02-0058 [accessed May 22, 2017].

[2] Washington in The Daily Journal of Major George Washington in 1751-2 Kept While on a Tour from Virginia to the Island of Barbadoes, J.M. Toner, ed., Albany, NY: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1892: 52.

[3] Washington in Toner, 47-8.

[4] Washington in Toner, 62.