Welcome back to our 3-Part Blog charting tuberculosis (TB) in the extended Washington Family. If you are new to this series, Part I examined how the disease works, charted its history and explained standard courses of treatments in the 1700s. Part II looked at victims from George’s generation, including his brothers Lawrence and Samuel and brother-in-law Fielding Lewis. You can find those blogs here and here. In our final entry, we will continue to look at individuals who suffered from the disease and see more evidence of how the disease stayed within a family.

George Steptoe Washington (1771-1809, aged 37)

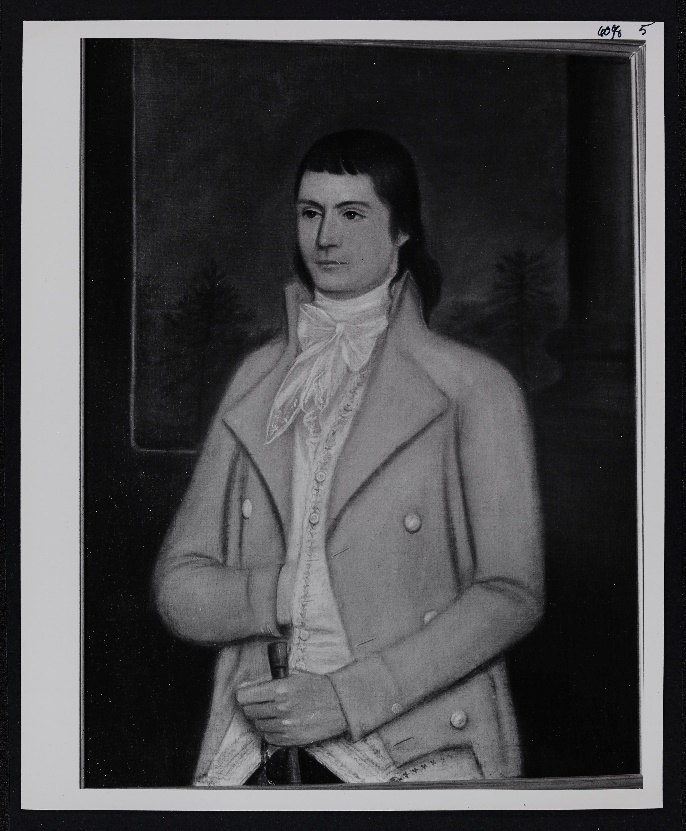

As covered in Part 2, George’s brother Samuel died of tuberculosis, as did several of his sons, including George Steptoe Washington. A product of his father’s fourth marriage to Anne Steptoe, George Steptoe became an orphan at age ten. He and his siblings then fell under the care of their uncle, George Washington. George Steptoe would go on to marry Lucy Payne, the sister of Dolly Madison. Like his father, the point of infection cannot be determined but is likely derived from a family member. George Steptoe certainly faced exposure to TB via his father from the moment of his birth but may have caught it later in life. Regardless, his health experienced a serious decline sometime after 1800, and he ultimately traveled to Augusta, Georgia, in search of health benefits. He died there on January 10, 1809.

George Augustine Washington (1759-1793, aged 34) & Frances “Fanny” Bassett (1767-1796, aged 29): George Augustine was another nephew of George Washington through his youngest brother Charles and quickly became his uncle’s favorite. He joined the Mount Vernon household in the early 1780s but had already experienced several periods of ill health that forced him to take leaves of absence from the battlefield. A diagnosis of tuberculosis soon came, leading George Washington to take an involved interest in his nephew’s health. Despite having witnessed the lack of improvement made by his brother Lawrence during such ventures, George funded trips to Berkeley Springs, Barbados, and Bermuda for George Augustine. He returned in May 1785 “in better health than when he set out, but not quite recovered.”1

During George Augustine’s absence, Frances “Fanny” Bassett, Martha Washington’s favorite niece, officially joined the household. Upon his return, the two quickly formed an attachment and married on October 15, 1785. George Augustine later became the manager of Mount Vernon, but his health steadily declined, leading his uncle to describe him as “a shadow of what he was.”2 Despite barely being able to ride, George Augustine traveled to Berkeley Springs in October 1791 but would be bedridden and coughing up blood by August 1792. After battling the disease for over ten years, he finally succumbed in 1793. His death “had been long expected,”3 but nevertheless caused his uncle to feel “it very keenly.”4

The death of her husband left Fanny a young widow with three very young children. Unlike many in that situation, she retained a comfortable lifestyle. As the beloved niece of George and Martha, she always had a home at Mount Vernon and frequently served as an additional hostess. Regardless, she did not remain a widow for long and married Tobias Lear, secretary to her uncle, in August 1795. Sadly, she passed less than a year later, in March 1796, with Lear lamenting, “The Partner of my life is no more!”5 Thought to have died of TB, Fanny likely contracted it from George Augustine during their marriage.

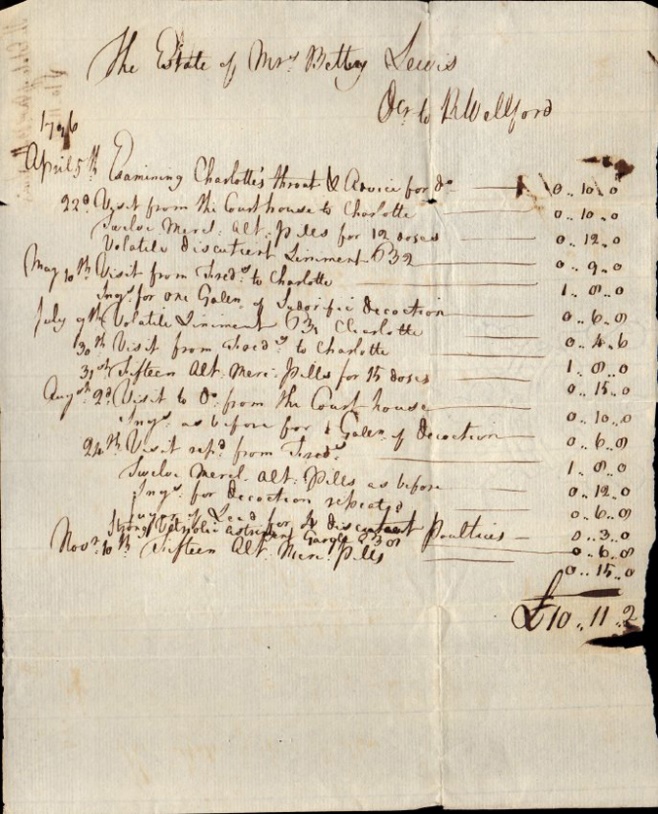

Charlotte (~1770-unknown, aged 27+): Charlotte served as an enslaved seamstress at Kenmore and later at Betty Washington’s final home, Millbrook. She first appears, aged eleven, in the 1781 probate inventory following the death of Fielding Lewis. Few details about her life exist apart from the record of a son, George, and another baby in a document from 1797. However, Charlotte clearly held an important position within Betty Washington’s household, given the medical records we have.

Charlotte took ill at Millbrook in 1796 with some form of respiratory complaint. Rather than care for Charlotte personally, Betty sent for the doctor seven times over the year. Charlotte underwent throat examinations and notably received treatment with mercury tablets and ammonia liniment for the chest. The former served as a common cure, which “purged” the body of any imbalances, while the latter mimicked early Vicks VapoRub by opening the airways. None of these treatments would have been pleasant, and the mercury certainly did more harm than good, but Charlotte recovered nonetheless. However, Betty Washington Lewis’ death in 1797 prompted the division of her enslaved staff. In an all-too-common occurrence, Charlotte and her son went to different properties (no mention of the baby exists). They likely saw little of each other after this or never met again. At age twenty-seven, we know Charlotte resided on a property owned by Charles Carter in Frederick County, Virginia. After this, she disappears from the record.

The true nature of Charlotte’s illness remains a mystery. She certainly suffered from a respiratory ailment and received treatment in line with that given to tuberculosis patients. Nevertheless, we cannot conclusively diagnose it as TB or determine if it ever affected her again. Despite this, her story reflects an important aspect of life in eighteenth-century Virginia and a failing of history. An interest in keeping the enslaved healthy enough to work existed, but the actual health of an enslaved individual often went undocumented. We only know of Charlotte’s illness due to the bill sent by the doctor listing dates and treatments. Even this reflects a rarity as the lady of the household generally oversaw medical treatment for the enslaved rather than a physician. Considering the widespread nature of TB, its higher prominence in poor and minority communities, enslaved living and working conditions, and the high death rates recorded amongst Philadelphia’s free Black population in the early 1800s, the disease likely accounted for a high number of deaths within Virginia’s enslaved population. Sadly, we may never know how many individuals died of the disease or its impact on their lives.

You can read the full details of Charlotte’s treatment and life here.

Hercules Posey (~1754-1812, aged roughly 64)

One Black individual known to have died of tuberculosis was Hercules Posey. Hercules came to Mount Vernon in 1767 after his previous enslaver, John Posey, failed to pay a mortgage owed to Washington. Having served as a ferryman for Posey, Hercules initially took up the same position. By 1786, he had moved on to the position of cook, for which he is best known. Highly skilled in his culinary abilities, Hercules counted amongst the nine enslaved individuals the Washingtons brought with them to Philadelphia in 1790. Early 1797, however, found Hercules working as a laborer at Mount Vernon, and he acted to self-emancipate in February. In doing so, Hercules left behind at least three children, Richmond, Evey, and Delia, who he shared with his late wife, Alice. Due to Alice’s status as a dower slave, none of their children would receive their freedom in Washington’s will.

After his escape, Hercules made his way to New York City, where he again worked as a chef. He died on May 15, 1812, with the cause given as TB, and his grave lies in the Second African Burying Ground in Lower Manhattan. Given the span of time between his escape to freedom and death, he possibly contracted the disease after leaving Mount Vernon. Then again, it remains entirely possible that he became ill while enslaved in Virginia or Philadelphia. In this case, he either suffered with an active case for many years, with periods of waxing and waning or had a dormant case that reactivated later in life.

Others: Additional members of the extended Washington family contracted the disease as time went on, and the same goes for the enslaved. However, an interesting aspect of tuberculosis is that far more individuals may have had it but remained unaware. As covered in Part I, TB can go dormant by walling itself off in the lungs. Minor symptoms would have appeared at the time of infection, but those pauses when the disease goes dormant. Depending on how long it remained active and how severe, the TB may have gone unnoticed or been misdiagnosed. If the disease never reactivated, a person could live a full life and never know they had it.

Today, we diagnose tuberculosis through symptom analysis and testing. Multiple successful treatments additionally exist to help people overcome the disease. For the 1700s, however, symptoms alone provided the diagnosis, and the dormant phase served as the only successful reprieve from the disease. The fact that our modern technology and medical knowledge would have saved many of the people covered in this 3-part blog appears evident. Nonetheless, it remains unclear just how many people in the extended Washington family actually contracted TB. This then raises the question, if TB testing had existed in the 1700s, would individuals such as George and Betty Washington have turned up positive?

Emma Schlauder

Research Archaeologist

Bibliography

Anderson, Alicia K. & Lynn A. Price (editors) 2018 George Washington’s Barbados Diary: 1751-52. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, VA.

Budinger, Meghan & Mara Kaktins 2020 Charlotte and the Mercury Pills. Lives & Legacies Blog, The George Washington Foundation <https://livesandlegaciesblog.org/2020/06/17/charlotte-and-the-mercury-pills/>. Accessed April 11 2023.

Chernow, Ron 2010 Washington: A Life. Penguin Books Ltd, London, UK.

5 Eliassen, Meredith, Tobias Lear. Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington’s Mount Vernon, George Washington’s Mount Vernon < https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/tobias-lear/>. Accessed April 11 2023.

1-4 Fore, Samuel K. George Augustine Washington (ca. 1759-1793). Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington’s Mount Vernon, George Washington’s Mount Vernon < https://www.mountvernon.org/library/ digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/george-augustine-washington-ca-1759-1793/>. Accessed April 11 2023.

Glen, Justin 2014 The Washingtons: A Family History, Vol 1, Seven Generations of the Presidential Branch. Savas Beatie LLC, El Dorado Hills, CA.

Lenhart, Chelsea Hercules. Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington’s Mount Vernon, George Washington’s Mount Vernon < https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/ article/hercules/>. Accessed 11 April 2023.

Rankin-Hill, Lesley M. 1997 A Biohistory of 19th-Century Afro-Americans: The Burial Remains of a Philadelphia Cemetery. Bergin & Garvey, Westport, CT.