One of my favorite historical objects in the collection are photographs. Not particularly for artistic reasons, but as a documentation of a moment, a time, a person, a world that no longer exists. During the Victorian era (1837-1901), there were extraordinary developments in the field of photography. In a span of forty years, photographs went from complicated metal plates, harsh chemicals, and long exposure times to inexpensive images on cardboard that could be taken, processed, and given to the sitter in minutes.

We have many pictures in our collection, and we can trace the development of photography through images of Lewis family descendants.

A Pleasant View of Burgundy

The widely accepted creator of photography as we know it was French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. He produced the first surviving photograph around 1826 showing the scene from his window in Burgundy. After Niepce’s death, his former associate, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, continued improving Niepce’s photographic process, introducing the “daguerreotype” in 1839. (The University of Texas Austin, 2024) To create an early daguerreotype, a polished silver-plated copper sheet was treated with iodine vapor to make it light-sensitive. After exposure, the plate would be developed with mercury vapor and fixed with sodium chloride. This was a tedious and complex process that required the subject to remain entirely still for three to fifteen minutes. (Stewart, 2018) (The Library of Congress, 2024) (Department of Photographs, 2004) The process was amended and, by the 1850s, used large glass-plate negatives, allowing for a crisper picture and a much shorter exposure time. (Department of Photographs, 2004)

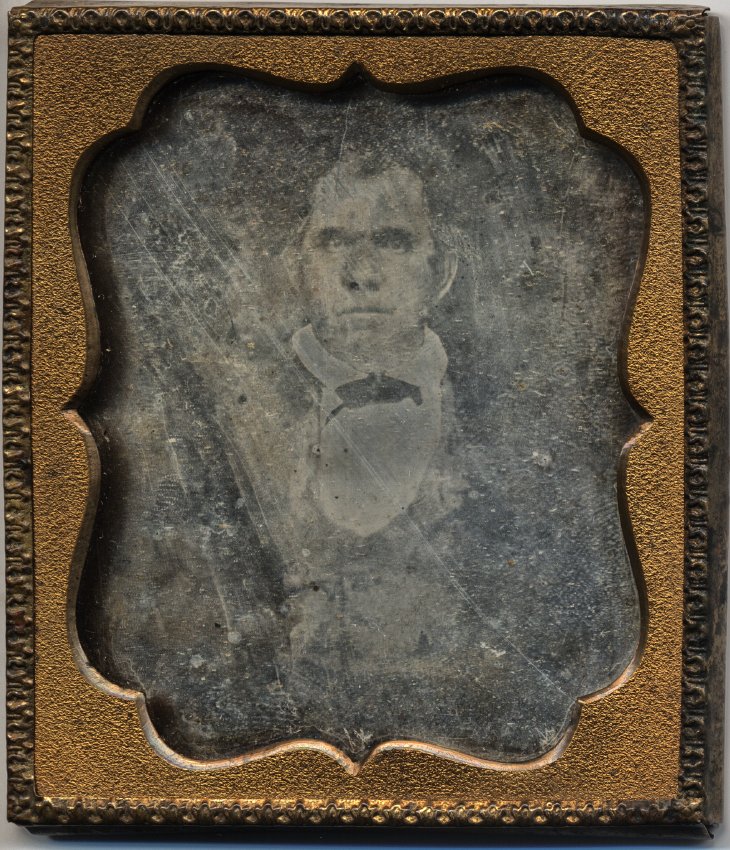

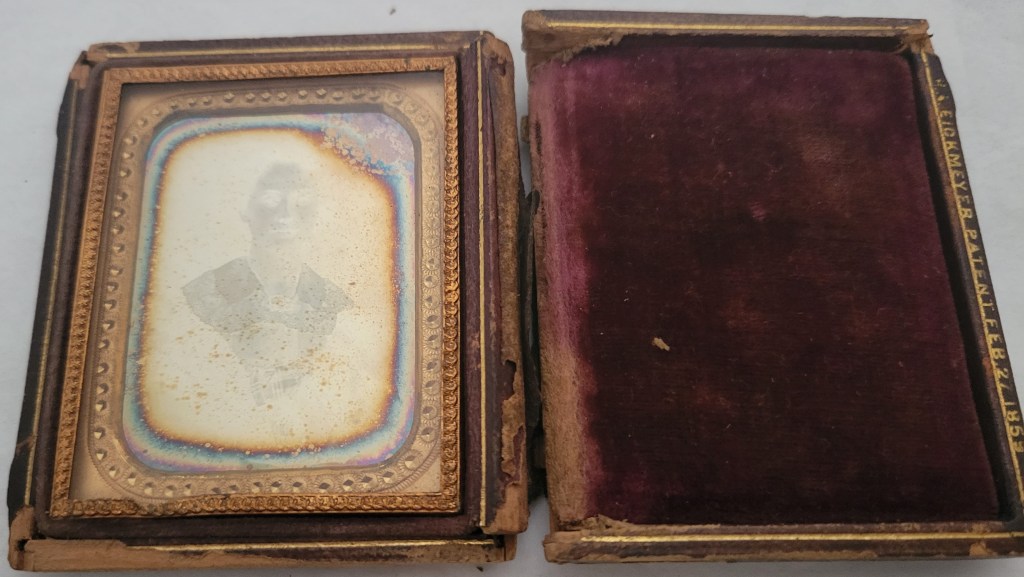

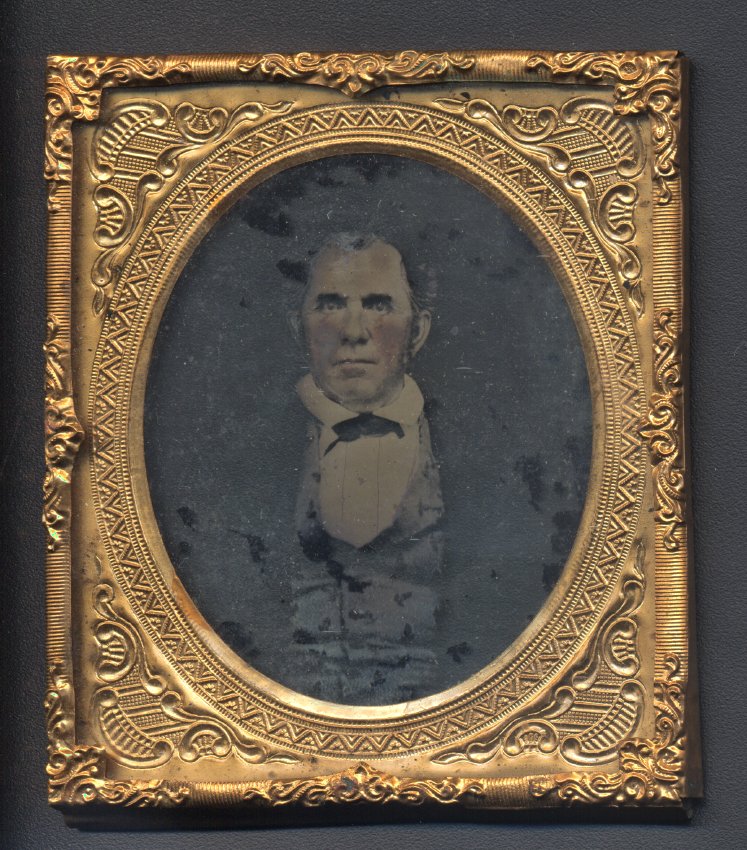

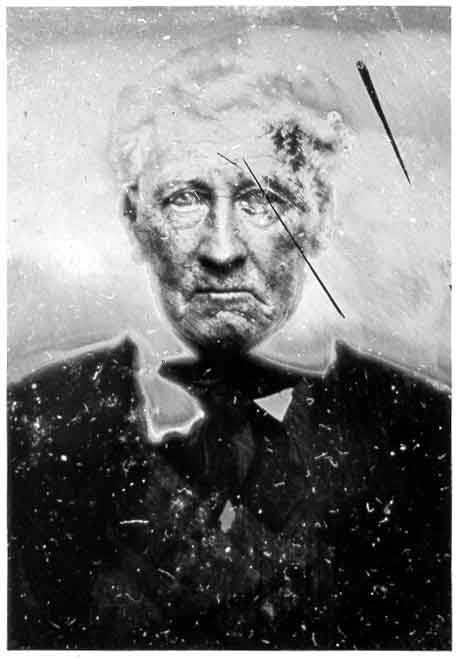

We have three daguerreotypes in the collection dating circa 1850s. They are all portraits housed in elaborate leather cases with gilt-metal frames. The larger photograph is called a sixth-plate daguerreotype portrait of John Taliaferro Lewis (1785-1862), who was the grandson of Charles Lewis, Fielding Lewis’s brother. John was a Methodist minister and lived at “Stepney” near Manassas. Through his wife, Francis Tasker Ball, he became the owner of “Portici,” also near Manassas. The two smaller ninth-plate daguerreotypes are both portraits of Ellen Lewis Nye (1834-1886), the granddaughter of Howell Lewis, the ninth son of Fielding and Betty. She married Anselm Tupper Nye, and they resided in Ohio, where they were both buried.

Images for Loved Ones

The daguerreotype was soon replaced in popularity by the ambrotype and tintype, which were both cheaper and easier to develop. (Harding, 2013).

An ambrotype is comprised of an underexposed glass negative placed against a dark background. The dark backing material creates a positive image. They were sold in either cases or ornate frames to provide an attractive product and to protect the negative with a cover glass and brass mat. (Library of Congress, 2024)

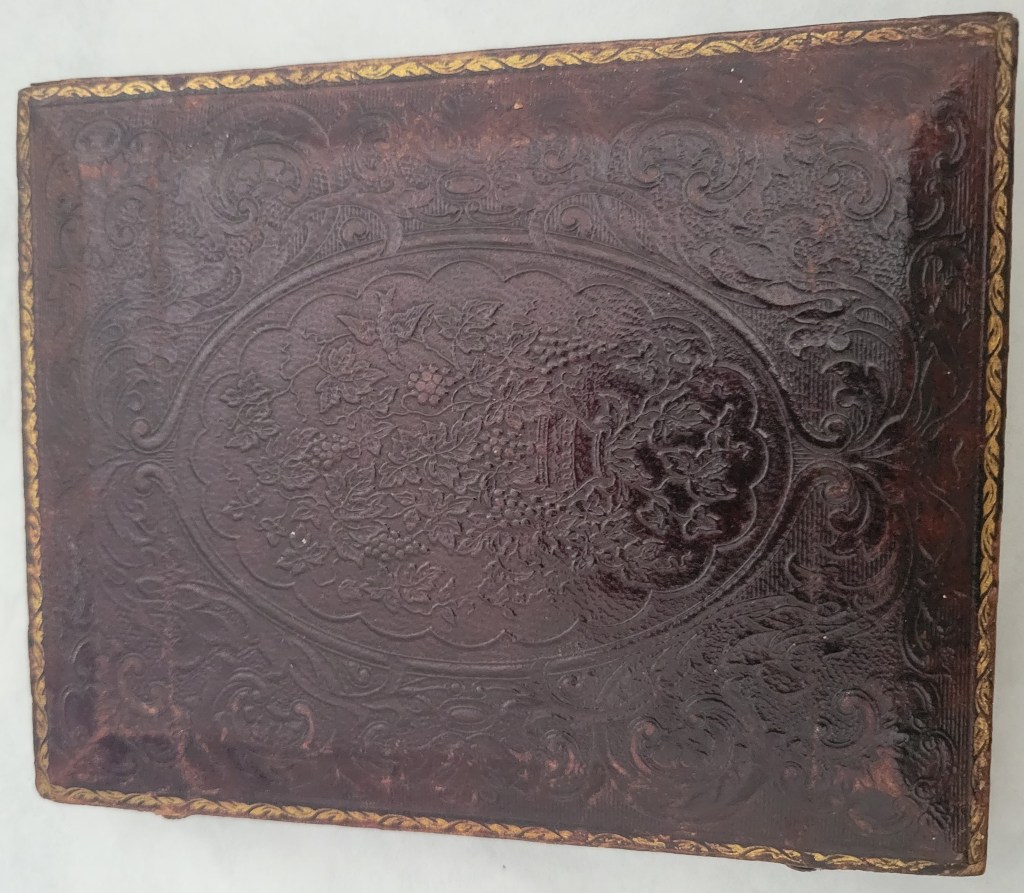

We have three ambrotypes in the collection: a landscape and two portraits. The landscape dates to circa 1855 and shows a group of people gathered around Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon. Two of the figures were Thomas Coatsworth (1821-1887) and his wife Electra Weller Coatsworth (1832-1869). It is housed in an embossed leather case.

One portrait is of John Taliaferro Lewis and is almost identical to his daguerreotype. The other portrait is of Daingerfield Lewis (1785-1862). It dates from the same time and is held in a leather case. Daingerfield Lewis was the son of Captain George Lewis, the fourth son of Fielding and Betty, who served in the Continental Army under his uncle George Washington.

Tintypes became especially popular because the photographer could take a picture and develop it within just a few minutes. It was called the new “instant photo.” This “instant photo” could be found at fairs, carnivals, and on the boardwalk, not just professional studios. Due to the tintype price, weight, and unbreakable nature, they became extremely popular during the Civil War because soldiers were able to mail them back to loved ones. (Stewart, 2018)

The three tintypes in the collection are a group of siblings, two brothers, and one sister (there were eight total siblings). George Lewis (1832-1883), Fielding Lewis (1839 – 1863) and Betty Fitzhugh Lewis (1847-1920). Their father was Howell Lewis Jr. (1808-1883), the son of Howell Lewis and grandson of Fielding and Betty. Howell Lewis Jr. was one of the earliest settlers of Henry County, Missouri, and established Lewis Station (now called Lewis, Missouri). There is not much information on the siblings besides the basics. George Lewis, the eldest, was born in West Virginia, died in Nevada, and is buried at the Lewis Station Cemetery. Fielding Lewis was born in Missouri and died young during his service with the Confederate army in Texas. Betty Fitzhugh Lewis was born in Missouri as well; he married Milton D Finks, had at least three children, and is buried in Calhoun cemetery.

Paper, Cardboard, and Formality

By the later part of the nineteenth century, paper photos mounted on cardboard became more popular. Carte-de-visite became quite a fad after carte portraits of Queen Victoria with her husband and children were published. (Harding, 2013). Part of why they became popular is they were cheaper to produce because multiple images (eight) could be taken with the same photographic plate, cut into small portraits, and mounted to heavy cardboard. (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 1998)

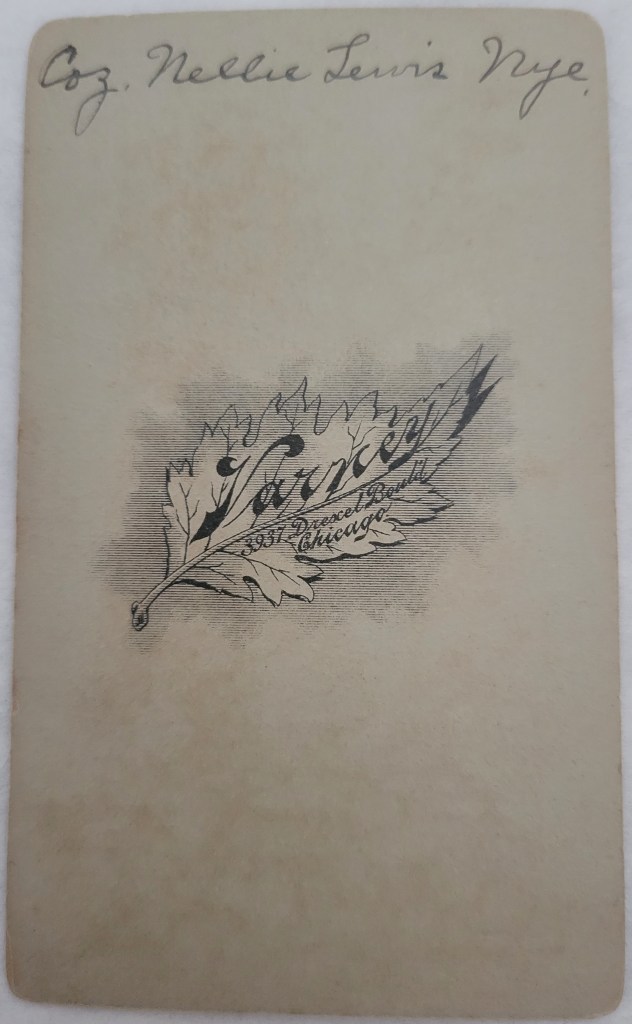

Two of our carte-de-visites are portraits of two young ladies around 1860. One is Ellen Lewis Nye, who previously appeared in daguerreotype around the same time. The second is Mary Ellen Lewis Hogan (1834-1874), who was the daughter of Howell Lewis, Jr. and sister to George, Fielding, and Betty Lewis. She was born in West Virginia, married Robert Henderson Hogan, and is buried in Illinois.

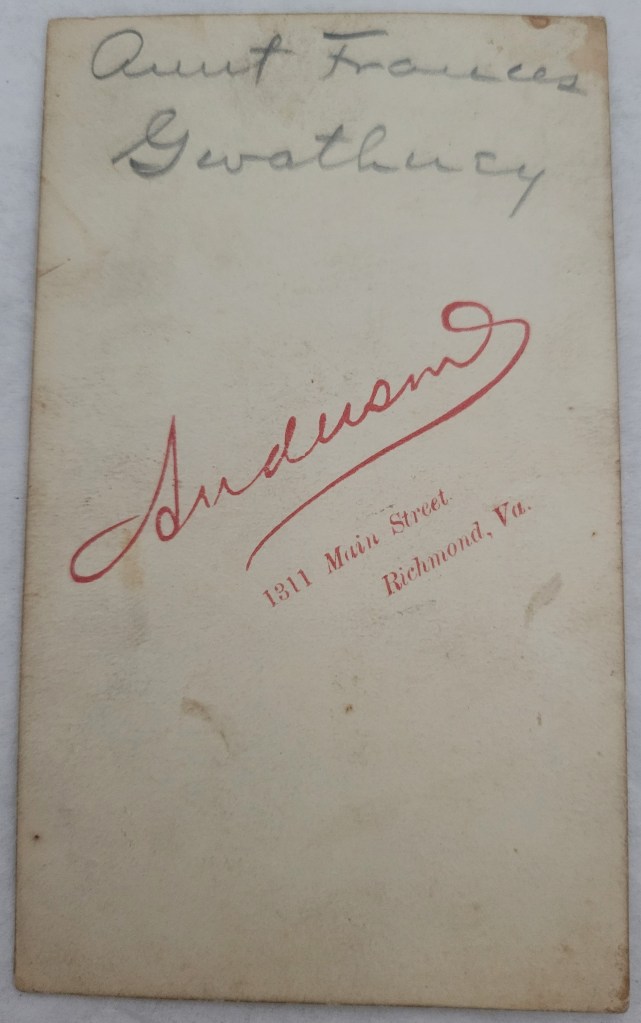

The carte-de-visite was gradually superseded by the cabinet card, which remained popular until the introduction of the Kodak Box Brownie camera in 1900. (City Gallery, 2005) The cabinet card marked a transition from more formal portraiture to amusing, personal, and even candid images. They were taken in studios that were equipped with lights, props, and sometimes even hair and makeup. The average price was around $1.50 for a dozen cards, which is around $45 today. (Salvesen, 2021)

Our cabinet cards date from 1850 to 1897 and are portraits of three females who, like all the others, are descendants of the Lewis family. The oldest is of Francis Fielding Lewis Gwathmey (1808-1888), and it was taken around 1850, putting her in her early forties. Her father was Howell Lewis, son of Fielding and Betty and sister to Howell Lewis Jr. Francis married Rev. John “Parson” Blair and had twelve children, of which only three outlived her. She is buried in Richmond, Virginia.

We have another picture of Ellen Lewis Nye, who has previously been represented in daguerreotype and carte-de-visite. The card was taken in 1885, shortly before her death. The last one is Virginia Tayloe Lewis (1842-1916), taken during the Christmas season of 1897. She was born in Washington, D.C., at The Octagon House. She was the daughter of Captain Henry Howell Lewis and great-granddaughter to Fielding and Betty.

Money and the Magic Lantern

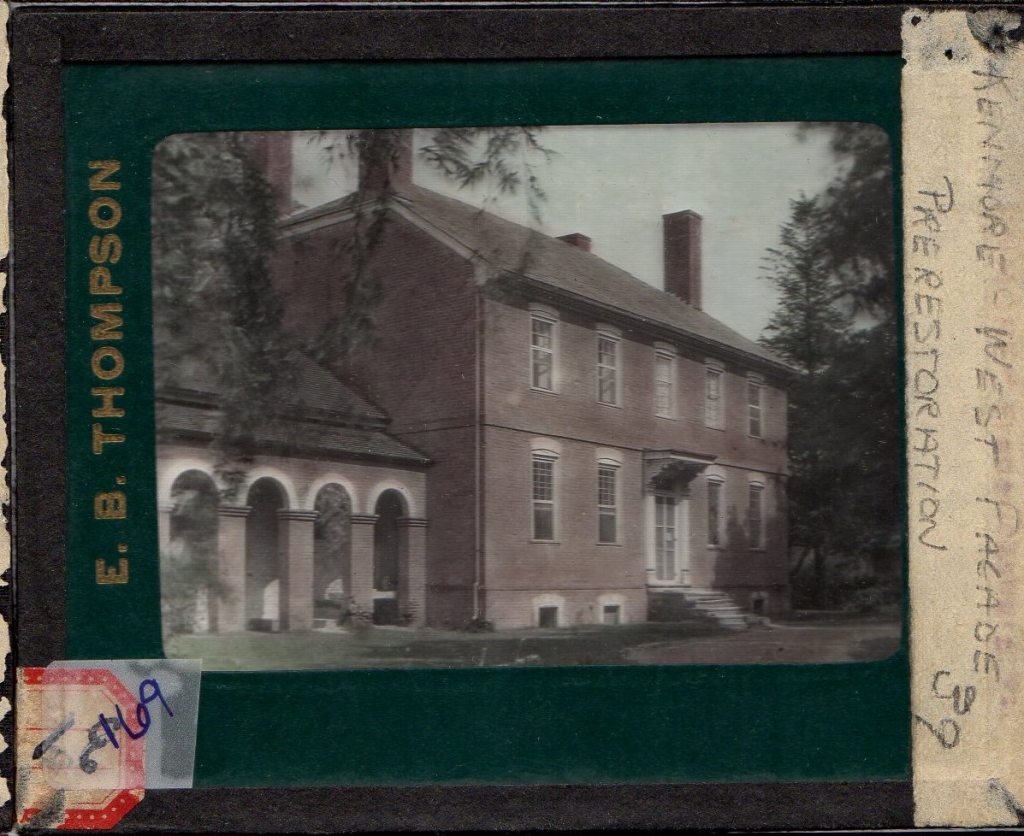

This is a brief history of photography seen through the descendants of the Lewis family. But make no mistake, these are not the only important pictures in our collection. There are still trays of glass slides that belong to a curious device called the “lanterna magica,” which became an invaluable tool that, along with gingerbread, helped restore Kenmore.

Heather Baldus

Collections Manager

Bibliography

City Gallery. (2005). Cabinet Card. Retrieved from City Gallery: http://www.city-gallery.com/learning/types/cabinet_card/index.php

Department of Photographs. (2004, October). The Daguerreian Era and Early American Photography on Paper, 1839–60. Retrieved from The Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/adag/hd_adag.htm

Harding, C. (2013, June 27). How to spot a carte de visite (late 1850s–c.1910). Retrieved from The National Science and Media Museum: https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/find-out-when-a-photo-was-taken-identify-a-carte-de-visite/

Harding, C. (2013, May 25). How to spot a ferrotype, also known as a tintype (1855–1940s). Retrieved from The National Science and Media Museum: https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/find-out-when-a-photo-was-taken-identify-ferrotype-tintype/

Library of Congress. (2024). Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs. Retrieved from Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/collections/liljenquist-civil-war-photographs/articles-and-essays/ambrotypes-and-tintypes/

Salvesen, B. (2021, June 28). The Return of Cabinet Cards. Retrieved from Los Angeles County Museum of Art: https://unframed.lacma.org/2021/06/28/return-cabinet-cards

Stewart, J. (2018, December 31). Tintype Photography: The Vintage Photo Technique That’s Making a Comeback. Retrieved from My Modern Met: https://mymodernmet.com/tintype-photography/

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (1998, July 20). Carte-de-visite. Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/technology/carte-de-visite

The Library of Congress. (2024). The Daguerreotype Medium. Retrieved from The Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/collections/daguerreotypes/articles-and-essays/the-daguerreotype-medium/

The University of Texas Austin. (2024). The Henry Ranson Center. Retrieved from The University of Texas Austin: https://www.hrc.utexas.edu/niepce-heliograph/