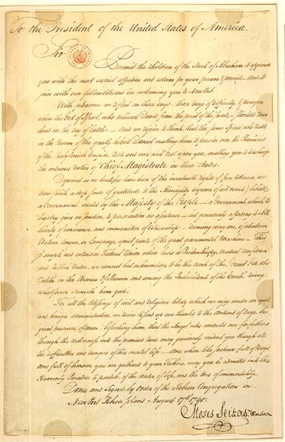

The quote, “To Bigotry, No Sanction, To Persecution No Assistance” appears in a 1790 letter written by George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, RI (Fig 1). Of all the words Washington committed to paper, these rank amongst the most important, yet he merely adapted them from a letter sent by the Congregation itself.

By 1790, Jewish communities in the newly formed United States desired to confirm their place in society and the freedoms promised under the founding documents. Washington’s visit to Newport, RI, that year allowed direct access to a government representative for a community seeking reassurance. Their letter moved Washington, yet he was no stranger to the lives and likely concerns of the wider Jewish American community.

The Jewish Diaspora and Settlement in the Americas

For those unfamiliar with the Jewish diaspora (Def: the dispersion of a people from their original homeland, in this case, Israel, through forced or voluntary migration), the current Jewish population of the United States largely consists of Ashkenazi Jews whose ancestors settled in central and eastern Europe before immigrating to the States. While some Ashkenazim moved to the Americas during the colonial period, the majority emigrated during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Nonetheless, Jews have lived in the Americas since the 1500s, they simply belonged to another sect of the diaspora.

Sephardic Jews descend from those who settled on the Iberian Peninsula. Infamously pushed out of the region or forced to convert during the Inquisition, many initially sought refuge in Portugal (briefly), North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, and the Netherlands. As restrictions in some of these areas increased, numerous families forged proof of Christian ancestry to emigrate to Brazil and the Spanish colonies before seeking more religious freedom in British territories.

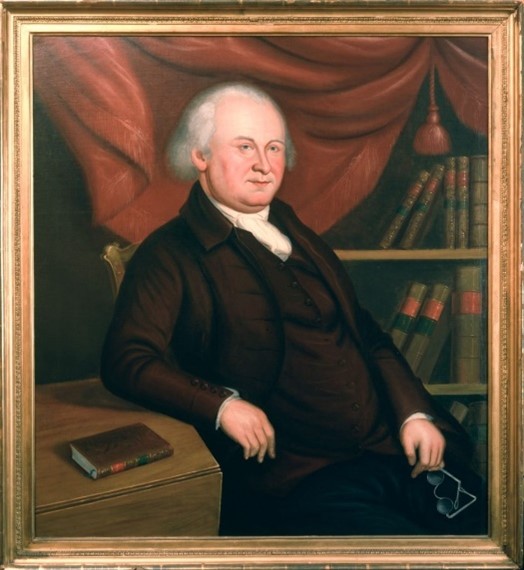

Here, those who had seemingly converted, but continued to practice as Crypto-Jews, shed their Catholic personas and openly embraced their ethnoreligious identity. Aaron Lopez (1731-1782), called the “Merchant Prince of Newport,” serves as one example (Fig 2). Born Duarte Lopez in Portugal, he moved his wife Anna and daughter Catherine to Newport, RI, in 1752, where they reclaimed their Jewish identities under the names Aaron, Abigail, and Sarah.

Several organized Jewish communities ultimately emerged in New York City, Newport, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Savannah. These areas proved ideal due to their nature as trade centers and rules, allowing more religious, political, and business freedom for non-Christians. Still, Jews lived and worked throughout the thirteen colonies as active members of the wider community, and many crossed paths with George Washington and those he knew.

Colonial Virginia

Jewish history in Virginian territory began when Joachim Gaunse, a Bohemian metallurgist, joined the Roanoke Colony in 1585. However, he escaped the fate of the Lost Colony by returning to England in 1586. A later instance of Jewish settlement occurred when Elias Legarde/o arrived in the Jamestown area in 1621. After that, small, scattered groups emerged throughout the colony, and the first Jews in the greater Fredericksburg area arrived by 1652. Nonetheless, they could not hold citizenship or public office as these statuses required oaths invoking the Christian faith.

Jewish presence in Fredericksburg and other cities meant that Washington and his associates lived and worked alongside Jewish community members all their lives. In staying active in the community, many Jewish men, including the majority mentioned in this blog, joined the Masons. Specifically, (H)ezekiel Levy appears in Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4’s records as the sole Jewish member in 1776. As Washington maintained a life membership with his mother lodge from 1752 onwards, the two men potentially knew each other (Fig. 3).

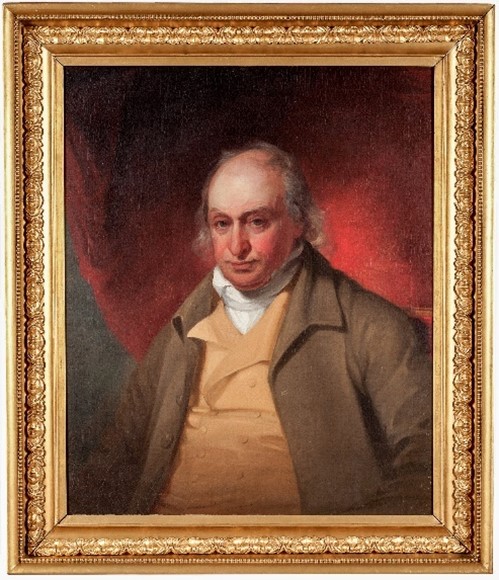

Other Jewish residents of Fredericksburg and businessmen likely crossed paths with Fielding Lewis. The Gratz brothers of Philadelphia, Barnard, and Michael, built a business network that spread across the colonies (Fig 4). They supplied Virginian troops during the French & Indian War and set up trade in Fredericksburg by 1776, where their associate Joseph Myers handled business affairs. Henry Mitchell, a one-time friend of the Lewises, counted amongst those who did business with the Gratzes and Myers. Like their gentile counterparts, however, Jewish merchants engaged in all aspects of the economy. This included the Atlantic and domestic slave trade, from which they profited, advanced, and purchased individuals.

As Washington’s career took off, he came into closer contact with Jewish Virginians. Jacob Myer and Michael Franks served alongside Washington in the build-up to the French & Indian War, and the latter fought at the Battle of Fort Necessity (July 3, 1754). In 1769, Washington sought the services of Williamsburg’s Dr. John de Sequeyra for his stepdaughter Patsy Custis’ epilepsy (Fig. 5). Sequeyra, a well-respected physician, arrived in Virginia in 1745, wrote about diseases found in the region and served as the first visiting physician at, and later director of, Williamsburg’s Public Hospital. While Thomas Jefferson often receives credit for popularizing tomatoes as edible, Jefferson himself credited Sequeyra.

American Revolution

Like the colonists typically pictured during the war, the American Revolution brought turmoil to Jewish communities. The majority supported the cause of independence, with leading merchants voicing dissent from the 1765 imposition of the Stamp Act. Others remained loyal to the crown as they knew where they stood in society. Regardless of which side they chose, Jews aided their cause as soldiers, merchants, and suppliers. Still, the war brought division, death, and poverty to many families.

The Touro-Hays family illustrates one such division. Issac Touro, head of the Newport Congregation, remained loyal to the British while his brother-in-law, merchant-banker Moses Michael Hays, sided with the Patriots (Fig 6). Despite holding opposing views, the two men used their positions to take a stand for the larger Jewish community. In 1775, Hays refused to sign a declaration of loyalty to the patriot cause until the authors removed the phrase “upon the true faith of a Christian.” When the British occupied Newport the following year, Hays, along with most of the congregation, fled while Issac remained behind. Using his connections, Touro ensured that the British left Newport’s synagogue largely untouched. Today, it stands as the oldest surviving synagogue in North America and answers to the name “Touro Synagogue” (Fig. 7). When it became clear that the British would lose, however, Touro moved his family to the Caribbean. The two sides of the family would only reunite after 1783, when Issac died, and his widow Reyna returned from Jamaica with their children to live with her brother Michael.

In all, approximately a third of the Jewish population served during the American Revolution from Bunker Hill to Yorktown. This included the lowest positions up to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, which Solomon Bush of Philadelphia held. This period additionally saw public office open to Jews, with numerous individuals serving on committees. The first known Jewish fatality of the war occurred on August 1, 1776, in South Carolina when Francis Salvador fell to the British-allied Cherokee during a skirmish. Two years prior, the colony elected him a delegate to the Provincial Congress; the highest political position held by a Jew at the time.

Many who served as merchants and financiers devoted their assets, like Fielding Lewis, to the cause. As ship owners, many outfitted privateers and helped run blockades. Haym Salomon, a Polish-born Jew from Philadelphia, served as the Continental Congress’ main financier, an agent to the French consul, paymaster for the French forces, and worked closely with Superintendent of Finance, Robert Morris (Fig. 8). Salomon committed his entire fortune to the war effort, and his most significant contribution came when he raised the funds for the Yorktown campaign at the personal request of Washington. Like many individuals, he never received reimbursement from the government and ultimately died penniless.

Early America

In the wake of independence, the United States faced uncharted territory. For minority groups, these uncertainties proved even more concerning. The arguments for revolution and documents written to establish the new nation spoke to religious freedom and social equality, but how far that stretched remained debatable.

In 1786, Thomas Jefferson took steps to ensure these freedoms by writing the Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom. Passed into law, the bill affirmed the right to choose one’s faith along with the separation of church and state in Virginia. Several years later, in 1789, Kahal Kadosh Beth Shalome became Virginia’s first established Jewish congregation. Jefferson’s stance on religious freedom would ultimately inspire Commodore Uriah Levy to purchase and preserve Monticello.

At this time, we return to where we started. In 1790, Washington made a trip to Rhode Island to acknowledge their ratification of the Constitution. On August 18, while Washington met officials and residents of Newport, Moses Seixas of the Jewish congregation read aloud a letter expressing gratitude to the President and government while expressing hope for tolerance and equality (Fig. 9). Its key passage reads:

“…erected by the Majesty of the People – a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance – but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental Machine…”

In writing the letter, the congregation wished to express their hopes for the future and receive assurance from their head of state that this future existed. On August 21, Washington replied to the letter thanking them for the “cordial welcome [he] experienced…from all…citizens” while reflecting on the difficulties of the past and how the future promised security. Then, using the congregation’s own words, he wrote that:

“It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people…for, happily, the Government of the United States…gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance…”

Washington closed his letter by wishing that “every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.” The following year saw the ratification of the Bill of Rights, which further solidified religious freedom and equality.

Despite efforts made during the founding era and successive periods, antisemitism has never gone away. Now, more than ever, we must work to uphold that the wishes, freedom, and security of those who served the United States since its founding.

Emma Schlauder

Research Archaeologist

Bibliography

Encyclopedia Virginia 2024 Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786). https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/virginia-statute-for-establishing-religious-freedom-1786/#:~:text=As%20part%20of%20the%20revisal,physics%20or%20geometry.%E2%80%9D%20Jefferson%20was. Accessed 10 December 2024.

Fort Necessity: National Battlefield Park 2015 Roster of Virginia Regiment. https://www.nps.gov/fone/learn/historyculture/roster.htm. Accessed 12 December 2024.

Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life N.D. Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities – Virginia. https://www.isjl.org/virginia-encyclopedia.html. Accessed 9 December 2024.

N.D. Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities – Fredericksburg, Virginia. https://www.isjl.org/virginia-fredericksburg-encyclopedia.html#:~:text=Although%20there%20were%20Jews%20living,1850s%20and%20opened%20mercantile%20stores. Accessed 9 December 2024.

Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present 2018 Michael Gratz (1739-1811). https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/michael-gratz/. Accessed 11 December 2024.

Jewish Virtual Library N.D. Virtual Jewish World: Virginia, United States. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/virginia-jewish-history. Accessed 9 December 2024.

John L. Loeb, Jr.: Database of Early American Jewish Portraits N.D. Barnard Gratz. https://loebjewishportraits.com/biography/barnard-gratz/. Accessed 11 December 2024.

N.D. Michael Gratz. https://loebjewishportraits.com/biography/michael-gratz/. Accessed 11 December 2024.

N.D. Aaron Lopez. https://loebjewishportraits.com/biography/aaron-lopez/. Accessed 11 December 2024.

My Jewish Learning N.D. The Revolutionary War and the Jews. https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-revolutionary-war-and-the-jews/. Accessed 12 December 2024.

National Jewish Outreach Program 2016 Revolutionary Doctors. https://njop.org/revolutionary-doctors/. Accessed 12 December 2024.

The American Council for Judaism 1999 An Exploration of Four Hundred Years of Jewish History in Virginia. http://www.acjna.org/acjna/articles_detail.aspx?id=367>. Accessed 9 December 2024.

Touro Synagogue: National Historic Site N.D. Jews in Early America. https://tourosynagogue.org/history/jews-in-early-america/#early-jews-american-history. Accessed 9 December 2024.

N.D. George Washington Letter, 1790. https://tourosynagogue.org/history/george-washington-letter/. Accessed 10 December 2024.