We have a lot of silver in our collections, ranging from candlesticks to teapots to spoons. With all the silver, I have become familiar with eighteenth-century silversmith marks, but I have never explored the artisans behind the marks.

I was pleasantly surprised to find at least four women silversmiths represented through various pieces. These four women were all London-based traders within an active community of women artisans in luxury trades. I wanted to discover how these women entered this male-dominated trade and registered their marks. (City Women, 2025)

First, we need a little background to understand how the silversmith trade worked in eighteenth-century England.

The Trade

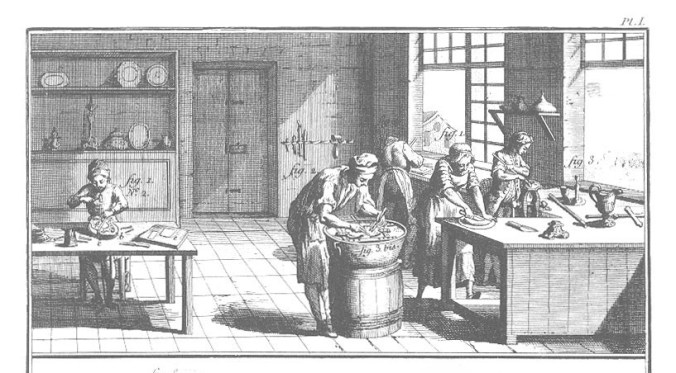

In the eighteenth century, English silversmiths were much more regulated than American silversmiths due to having around a four-hundred-year head start in establishing trade organization. However, no one on either side of the ocean would have been considered a master craftsman without a long multi-year apprenticeship.

While this was a rare path for girls, these four women were introduced to silversmith work through their families without formal apprenticeships. However, that doesn’t mean they didn’t spend years becoming expert artisans and learning to run a successful business from their fathers, brothers, and husbands.

When a silversmith obtained their “free” status, it meant they could sell their ware in the city of London. To earn this status, the silversmith had to be granted a hallmark from a Livery, like the Goldsmith’s Company. Women were only granted a mark if they were the widows of a silversmith. (Rue Pigalle, 2025)

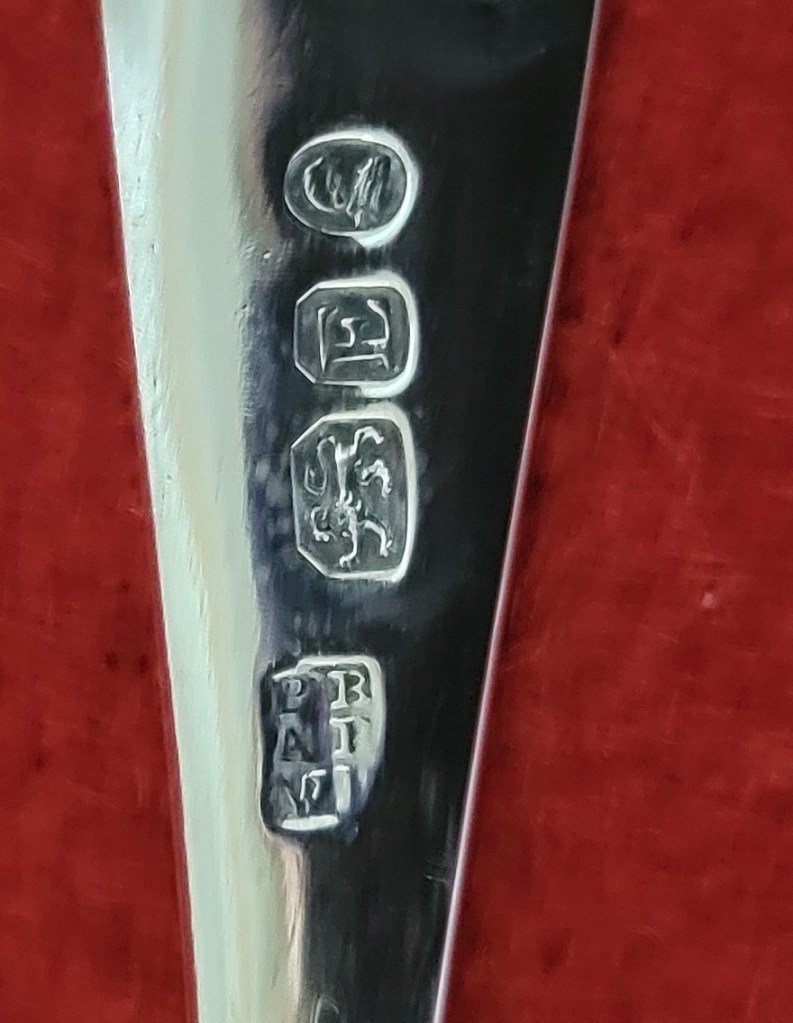

The Marks

In eighteenth-century England, the silversmith could sell the articles they made only after the pieces had been assayed and stamped with appropriate hallmarks. (Ford, 2018)

One hallmark is the symbol of the guildhall where it was assayed. Each location had a different image, like a London goldsmith guild’s head of a leopard, and has been used for over seven centuries.

Another is the maker’s mark, which has been required since 1363. This mark is now always the marker’s initials, but one was more often a trade symbol.

The mark of English sterling standard fineness—a lion passant—has been used since 1544 to certify that the metal is 92.5 percent pure silver. (Ford, 2018)

There is also a date mark indicated by a letter representing a year.

Finally, duty marks on silver from 1784 to 1890 reflect the tax on precious metals with the profile of George III or Victoria. (Arkell, 2025)

The Silversmiths

Hester Bateman

One of the most well-known eighteenth-century London silversmiths is Hester Bateman. She became the matriarch of the renowned Bateman family silversmithing company.

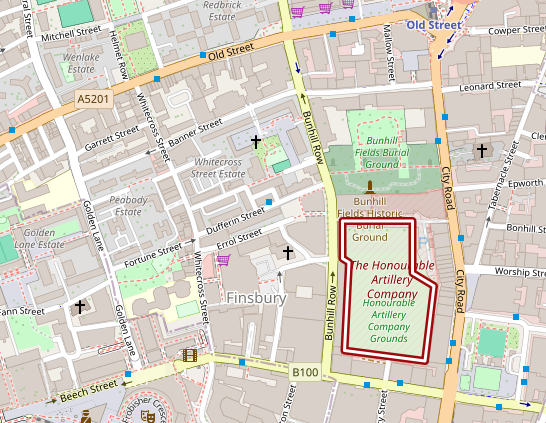

She was born Hester Nedem in London in 1708. She grew up poor with little formal education. In 1732, she married John Bateman, a goldsmith and chain maker. John died in 1760 of tuberculosis and left Hester his tools in his will. Hester took over the shop located at 107 Bunhill Row and registered her mark at London Goldsmith’s Hall on April 16, 1761. (Bly, 2008)

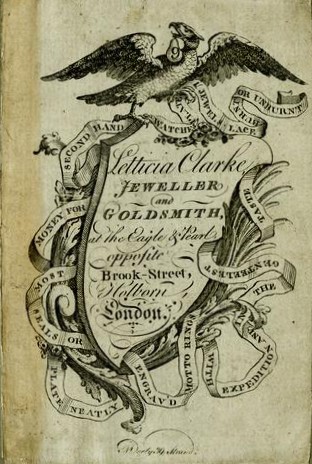

She continued to run the business for over thirty years, bringing two sons, one daughter (Letitia Clarke), and a daughter-in-law (Ann Bateman) into it. (Eagle and Pearl, 2025) The Bateman silversmith company specialized in household silver, such as flatware, cruet stands, and fashionable tea and coffee sets. (Slavid, 2021) The company’s work is characterized by bright-cut engraving and piercing in the neoclassical style.

The key to Hester’s success was adopting and integrating modern technologies, taking advantage of new cost-effective manufacturing processes to supply elegant wares to the middle class. (Slavid, 2021) One of the new cost-effective processes they used was the “Sheffield Plate,” developed in the 1740s. It is a fusion of copper and sterling silver to create gauge sheet silver, which can be punched and pierced by machines and is cheaper to produce than solid silver. (Campbell, 2006)

Hester retired in 1790 and was succeeded by her sons, who registered their hallmarks in December 1790. The Bateman family company continued for another fifty years, closing under William Bateman in 1843. (Campbell, 2006)

Ann Bateman

One of the renowned Bateman silversmith family members was Ann Bateman, daughter-in-law of Hester, who was married to her son Jonathan.

She registered her first mark in 1791, the year her husband died. She then worked in partnership with her brother-in-law Peter and eventually her son in 1800. Her works were popular tableware in fashionable neoclassical styles. (Bly, 2008)

Elizabeth Godfrey

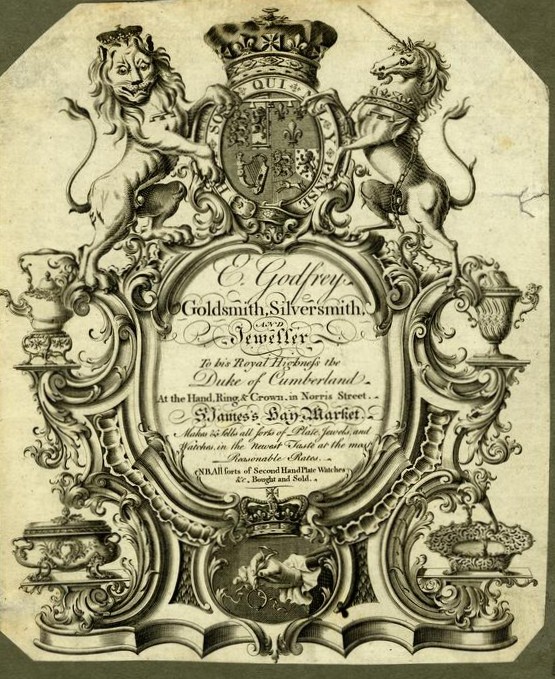

Elizabeth was born in London, the daughter of Simon Pantin, a prominent silversmith. She was believed to have been trained in her father’s workshop. She married two silversmiths; her first husband was Abraham Buteux, a French goldsmith.

Abraham died in 1731, and she registered her first mark as Elizabeth Buteux for her shop in Norris Street. She continued her first husband’s business until her marriage to Benjamin Godfrey in 1732. Upon Benjamin’s death in 1741, she registered a second mark as Elizabeth Godfrey. (Arts, 2025) She is described on her trade card as “Goldsmith, Silversmith, Jeweller, [who] makes and sells all sorts of plates, jewels, and watches, in the newest taste at the most reasonable rates.” (Mrkusic, 2014)

After her second husband’s death, she took charge of the company and began producing silver pieces in the fashionable Rococo style. This earned her many loyal patrons, including the Duke of Cumberland. (Skerry, 2018)

Elizabeth Godfrey passed away in London around 1758. (NMWA, 2025)

Susanna Barker

Our last silversmith is Susanna Barker. Unfortunately, little information about her life exists, and only a few museums have her works. Barker was classified as a small worker, which means she produced small-scale pieces of precious metals. (The Goldsmiths’ Centre, 2025)

She worked at 29 Gutter Lane and registered her first mark on 25 June 1778, second on 12 August 1789, and third on 26 August 1778.

Women’s work throughout history has sometimes been overshadowed, undervalued, or not recorded. However, with these solid silver markings, the ladies cemented themselves into the history of the arts.

If you want to learn more about women in the arts, visit the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Heather Baldus

Collections Manager

Bibliography

Arkell, R. (2025, January 22). Hallmarks. Retrieved from Antiques Trade Gazette: http://www.antiquestradegazette.com

Arts, N. M. (2025, January 21). Elizabeth Godfrey. Retrieved from National Museum of Women in the Arts: https://nmwa.org

Bly, J. (2008). Discovering Hallmarks on English Silver. London: Shire Publications.

Campbell, G. (2006). The Gove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

City Women. (2025, January 21). City Women in the 18th Century: An Outdoor Exhibition of Women Traders in Cheapside. Retrieved from City Women: https//citywomen.hist.cam.ac.uk

Eagle and Pearl. (2025, January 21). Our Story. Retrieved from Eagle and Pearl: http://www.eagleandpearl.com

Ford, T. K. (2018). The Silversmith in Eighteenth Century Williamsburg. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg.

Mrkusic, P. (2014, July 7). Antiques Today. Retrieved from The South African Antique, Art & Design Association: http://www.saada.co.za/antiques-today-september-2011/

NMWA. (2025, January 22). Elizabeth Godfrey. Retrieved from National Museum of Women in the Arts: https://nmwa.org/art/artists/elizabeth-godfrey/

Rue Pigalle. (2025, January 21). Goldsmith’s Jewelry Series Part 2: The Women of Silversmithing. Retrieved from Rue Pigalle: https://www.ruepigalle.ca/blog-posts/goldsmiths-jewelry-series-part-2-sophia-tobin

Skerry, J. E. (2018). Beyond the working dates: reconstructing the life and career of Elizabeth Patin Buteux Godfrey. Silver Studies. The Journal of the Silver Society, 75-88.

Slavid, S. (2021, April 16). Hester Bateman: Domestic Silver in 18th Century England. Retrieved from Bonhams Skinner: https://www.skinnerinc.com/news/blog/hester-bateman-domestic-silver-in-18th-century-england/

The Goldsmiths’ Centre. (2025, January 22). Smallworker. Retrieved from The Goldsmiths’ Centre: http://www.goldsmiths-centre.org