As the United States and historic sites across the country, including the George Washington Foundation, prepare to commemorate the nation’s 250th anniversary next year, it might be easy for the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War II to become an afterthought. After all, the interpretation of Historic Kenmore focuses on the Revolutionary era; the home was already the better part of 200 years old in 1945. But the histories of Kenmore and Fredericksburg are as intricately intertwined with the Second World War as they are with the War of Independence, and the legacies of both conflicts resonate today.

Like many Americans, the women of the Kenmore Association sought during the war years to demonstrate pride in their nation and support for its troops. Annie Fleming Smith, then national secretary of the Association, showed her appreciation for the country’s military by opening Kenmore’s doors to thousands of service members stationed in the Fredericksburg area. The Association took them “through the mansion and served them iced tea and gingerbread.” It hosted lawn parties and entertained soldiers early in the day and late at night. Hosts told everyone in uniform “who passed over the Kenmore steps…about George Washington, and other great men, passing over these very same steps.”

Smith regarded the Association’s commitment to “making our American boys feel at home in a home of the Washingtons” as Kenmore’s way of contributing “to the defense of the nation.” She also hoped that visits to Kenmore would crystalize in servicemen a commitment to the U.S. ideals of freedom and democracy.

The commitment to helping the recently transplanted soldiers feel comfortable in town was admirable; however, there are no records of Smith or Kenmore welcoming Black servicemen, stationed along with their white counterparts at what was then A.P. Hill Military Reservation and other nearby military installations. Smith and other members of the Kenmore Association, along with whites across Fredericksburg, the South, and the country, apparently did not see any conflict between simultaneous support for liberty, as embedded in the founding documents of the United States, and a racist social system.

So how, in segregated Fredericksburg, did Black service members spend their leisure time? If the city’s white-led institutions, including Kenmore, did not welcome African Americans serving their country, Black Fredericksburgers proved happy to host the men fighting the Double V campaign—victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism and discrimination at home. Indeed, at least two Black fraternal organizations in Fredericksburg provided recreational opportunities to African American soldiers during World War II.

The city’s Black Odd Fellows lodge (located at 301 Charles Street), “under auspices of the Citizens Committee of Local Negros,” hosted at least one dance for African American soldiers from A.P. Hill. This dance, held in February 1942, came shortly after white officials implicated Black servicemen stationed at A.P. Hill and Fort Belvoir in a “near-riot” that began after a Fredericksburg police officer attempted to arrest a Black soldier for public intoxication.

Following the altercation between the soldiers and the city’s police, during which white officers beat a Black soldier and threw a tear gas grenade, the Free Lance-Star published a letter to the editor from local NAACP leaders calling for the establishment of a Black USO—since the white USO barred Black soldiers from entering— and more leisure opportunities for African American soldiers in the city.

Other efforts to make the city more welcoming to Black service members followed. In May of that year, a group of Black Fredericksburgers requested that “the city furnish recreational facilities, showers, soap and towels for colored troops stationed at Camp A. P. Hill.” According to the letter containing this request submitted to the City Council, “there were slightly over a hundred colored soldiers now stationed at Camp A. P. Hill and that there were no recreational facilities at Camp A. P. Hill or in the City of Fredericksburg for these colored troops.”

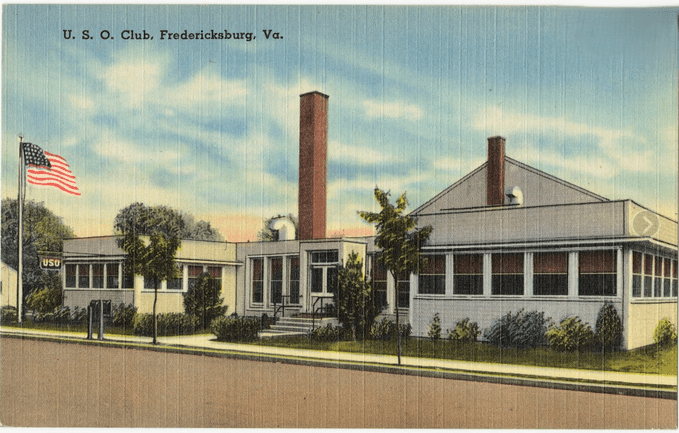

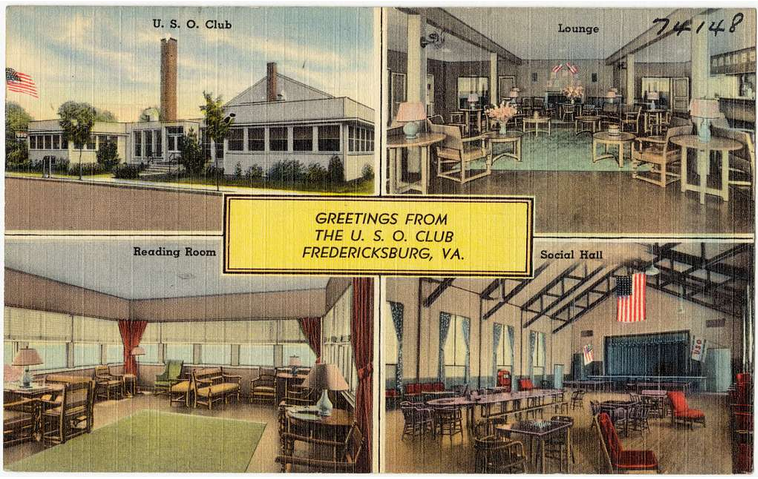

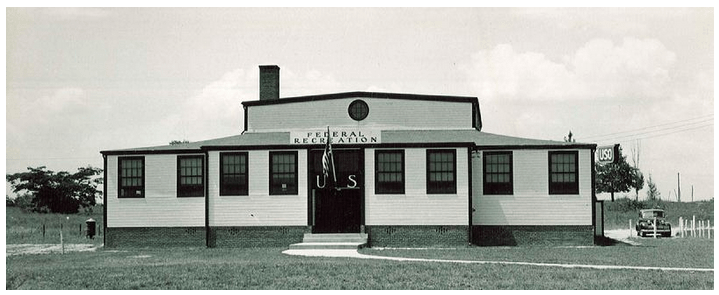

Eventually, the efforts of Black soldiers’ advocates succeeded: The Black USO sought by the NAACP leaders opened in June 1943 at Rappahannock Lodge 229 of the Independent Benevolent Protective Order Elks of the World (otherwise known as the African American Elks). Lodge 229 was at 1103 Winchester Street, just a block from Historic Kenmore. Across the world, USOs gave “troops somewhere to play cards, dance and socialize while taking a break from their duties.” Each USO facility was supposed to be “open to all men in uniform,” regardless of race, but in practice, centers were often segregated. Fredericksburg’s white USO opened in January 1942 at 408 Canal Street, which is today the Dorothy Hart Community Center.

Although Fredericksburg’s Black USO closed the following April, reportedly because of low attendance, another Black USO was completed in Caroline County in December of 1943 and was still operating in 1945.

However, the presence of these recreational facilities did not resolve tensions between white area residents and visiting Black service members. In the fall of 1943, while the Fredericksburg USO was open, A.P. Hill Military Reservation was home to the 366th Infantry Regiment, a Black unit. When members of the 366th chaffed against racism—for instance, by evicting the driver of a bus who instructed the soldiers to move to the back of the vehicle and finishing the drive back to A.P. Hill from Fredericksburg themselves—local whites reacted with fear. By November, the city’s white residents worried that the soldiers planned to “‘clean up the town on the first’” of December in objection to Jim Crow laws and segregation. Whites expressed relief when the unit shipped out before that date.

During World War II, the Kenmore Association opened its doors to white soldiers to share the stories of those Americans “who planned the principles, which is the beacon light of the world today.” Eight decades ago, the world’s democracies fought for those principles and defeated the forces of totalitarianism abroad, but racism endured at home. While progress has been made in the United States regarding the assertion “that all men are created equal,” the struggle against inequality continues.

Adam Nubbe

Manager of School & Youth Programs

Bibliography

Fredericksburg City Council. (1942, January). Fredericksburg City Council Minutes Vol 28. Fredericksburg, Virginia, USA.

Hall, D. (1943, November 27). Fearful Whites Relieved as 366th Leaves Virginia. Baltimore Afro-American, p. 21.

Johnson, S. (2022, February 7). How the USO Served a Racially Segregated Military Throughout World War II. Retrieved from USO: https://www.uso.org/stories/3001-how-the-uso-served-a-racially-segregated-military-throughout-world-war-ii

Salter, K. (2014). The Story of Black Military Officers, 1861-1948. London: Routledge.

Smith, A. F. (1941, December 26). Letter to Mrs. Barnum. Fredericksburg, Virginia, USA.

Smith, A. F. (1941, November 4). Letter to Mrs. Mitchell. Fredericksburg, Virginia, USA.

Smith, A. F. (1941, November 21). Letter to Mrs. Stone. Fredericksburg, Virginia, United States of America.

The Baltimore Afro-American. (1942, March 31). Soldier, On Furlough, Finds Vs. Prejudice Ignores War. The Baltimore Afro-American, p. 9.

The Free Lance-Star. (1942, February 9). Dance Friday Night for Negro Soldiers. The Free Lance-Star, p. 6.

The Free Lance-Star. (1942, January 31). Soldiers Causing Disorder Jailed. The Free Lance-Star, p. 1.

The Free Lance-Star. (1942, January 29). Tear Gas Quells Near-Riot Here. The Free Lance-Star, p. 1.

The Free Lance-Star. (1943, December 2). Colored USO in Caroline Completed. Fredericksburg, Virginia, USA.

The Free Lance-Star. (1943, June 3). New Colored USO is Dedicated Here. Fredericksburg, Virginia, USA.

The Free Lance-Star. (1944, November 14). USO Club in City To Be Withdrawn. The Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia, USA.

The Free Lance-Star. (1944, April 29). USO Cuts $7,200 Off Budget Here. Fredericksburg, Virginia, USA.

Woodfork Genealogy. (2025, January 27). USO Highway Number 2 Club. Retrieved from Woodfork Genealogy: https://woodforkgenealogy.com/caroline-county-virginia/uso-highway-number-2-club/

Wyatt, P. E. (1942, February 6). Negro USO is Seen as Need for City. The Free Lance-Star, p. 4.