Archaeology is trash. There, I said it. Before you call Mr. Jones and have me thrown in a pit of snakes, let me explain. Generally speaking, archaeology focuses on understanding the past through the items that people left behind, i.e., their trash. Most of the things we find are left around because they were broken or no longer needed. Disposal of these items looked much different before modern garbage collection as we know it today. Rather than trashcans and landfills, trash was often thrown outside of the home or workspace near windows and doors or any other designated disposal areas. These areas, also known as middens, usually have a high number of artifacts and are top-tier when it comes to understanding a site. So, in other words, archaeology is trash, and we love it.

Most people can get behind the archaeologists saving the trash that’s hundreds or thousands of years old, but things are a little different when it comes to saving more modern materials like plastic. When visitors or volunteers see things like plastic bottle caps or food wrappers in our bags to bring back to the lab, they usually have a few questions. Like, “Did you mean to keep this?” Or “Why are you keeping this trash?” Here at Ferry Farm, we don’t pick favorites, every bit of trash can tell us something about the site and how it has been used.

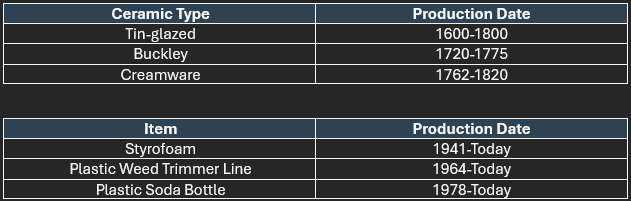

One-way modern materials can help us understand a site is by helping us determine the Terminus Post Quem (TPQ), or “time after which,” of a layer. The TPQ is determined by identifying the earliest production date of the most recently produced item. For layers deposited before the widespread use of plastics, ceramics are usually used for determining the TPQ because they are datable (temporally, not romantically) since most have very specific production dates, and they also hold up pretty well under ground. For example, when looking at the ceramics in a layer with tin-glazed wares, Buckley, and creamware, the TPQ would be 1762 since that is the earliest production date of the most recently produced ceramic (creamware). All the items in the layer had to have been deposited after that date.

The same idea works with modern synthetic materials like plastics, which are usually found at sites that have been used within the last 100 years. If there were to be some plastic soda bottles, weed eater line, and styrofoam in a layer, the TPQ would be 1978. While these materials may also be items you have in your home, not thought to be worth collecting and preserving, their presence in a layer helps provide a date. They can also tell us if an earlier layer was disturbed.

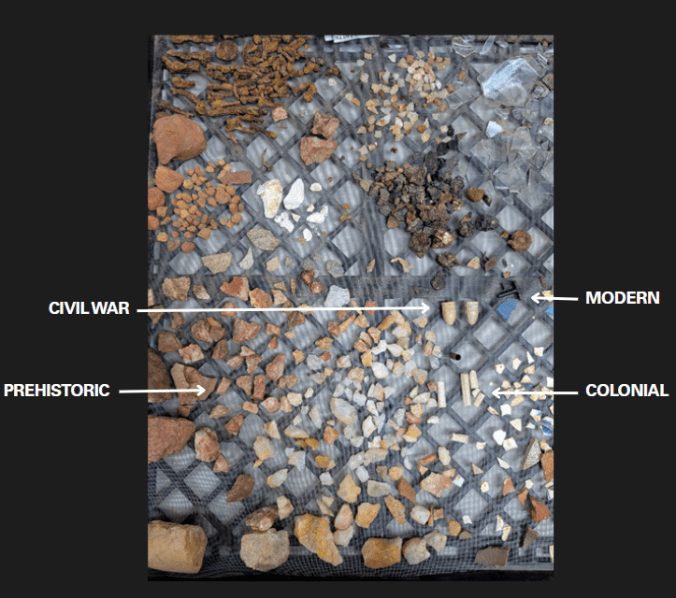

When archaeologists talk about disturbed layers, we aren’t judging their emotional state or love of 2000s heavy metal. Instead, when a layer is described as disturbed, that means there was some sort of activity happening after the initial deposition that affected that layer. During last season’s dig, there were layers with a mix of colonial, prehistoric, and modern materials that indicated that the area was disturbed by some subsequent activity. The information gathered by the presence of modern materials is important for the interpretation of the site and its use over time.

Now that we know why we keep this so-called modern trash. Here are a few examples of how the presence of these items helped our archaeologists understand a part of our site.

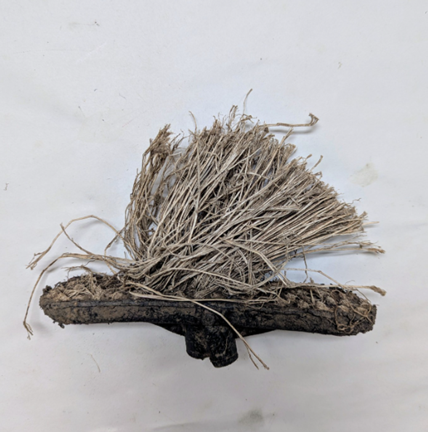

My favorite example happened during last year’s dig. One of our crew, Abbie, was preparing a feature for photographs and had to keep clipping pesky hairlike roots that were in the way. After a bit of excavating, it turns out the “roots” were bristles from a plastic broom. The broom dated the feature fill to the late 20th century and got to the root of the hairy soil issue.

Our staff has numerous examples of these modern materials being used to help identify previous archaeology as well, from candy wrappers at the bottom of shovel test pits and trenches to an entire trowel! While things like plastic trash bags and food containers aren’t the most exciting to find, they play a part in interpreting the history of activities on the site.

Once something is left behind, it becomes part of the archaeological record, whether it was 10,000 years ago or yesterday’s lunch. What does your trash say about you?

Danielle Arens

GWF Archaeologist