If you have followed the news of our excavations, you will have kept up to date with our building finds. The past two summers helped uncover evidence of one such structure, which we now believe represents a corncrib. While the name may seem self-explanatory, we have frequently heard the question, “What is a corncrib?” To answer this, we thought we would dedicate our newest blog to it.

Corn as a Crop

Long cultivated by Native Americans, early colonists quickly adopted corn into their agricultural repertoire. As a crop, corn proved easy to cultivate due to its hardy and adaptable nature, and its high yield to seed ratio made it a prosperous choice. The corn season lasted from planting in early May to the September-October harvest. After this, collected corn, counted as barrels, lay in corncribs. Husking and shelling occurred as needed since home consumption only required a small amount at a given time. This process continued throughout the winter months.

As a food staple, corn became an important part of free and enslaved diets in Colonial Virginia. Corn grew in such abundance that it reportedly fed everything. This led to Virginia husbandry relying on the crop and any decline in quantity led to a state of distress. As for the enslaved, records of food rations allotted to enslaved communities often refer to “pecks” or “bushels” of corn. Corn served as a useful ration since small amounts went far and multiple uses for it existed. It also provided better nutrition, which did not go unnoticed by enslavers. Instances of enslaved rations excluding corn resulted in a decline in health, energy, and production. This made the inclusion of the staple essential.

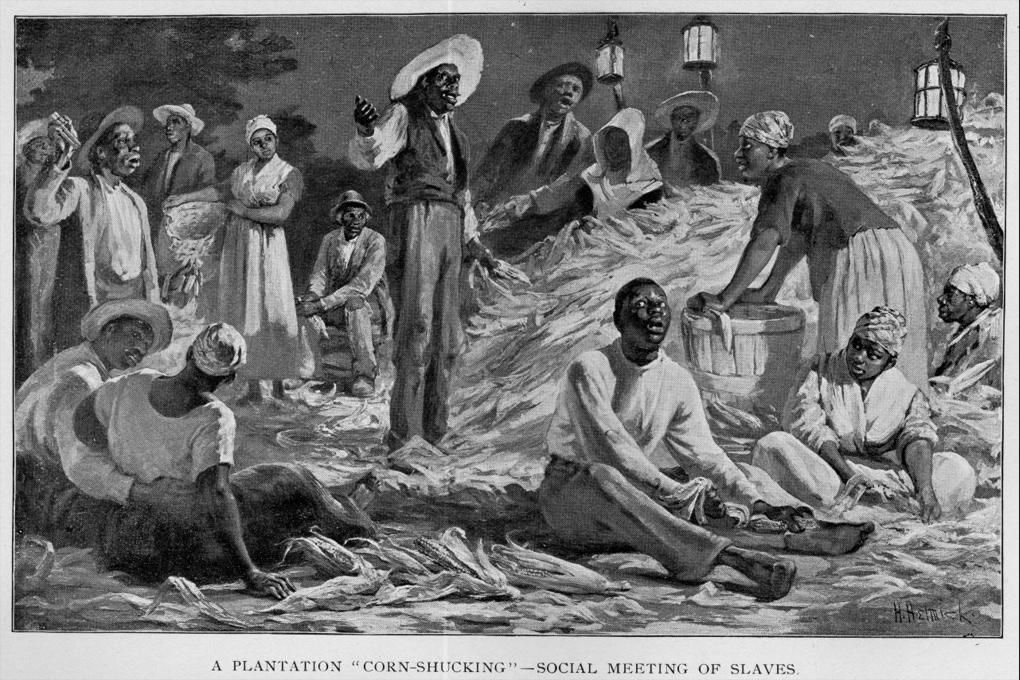

Despite their forced labor, enslaved communities integrated corn harvesting into their culture. Annual so-called corn shucking festivities proved frequent sights on plantations, especially as corn production expanded. During this time, the harvested corn lay in heaps next to the crib. As the size of the harvest required many people for husking, this event provided time for socializing. A moment filled with music and dance, even neighboring enslaved individuals and relatives not attached to the property could attend under the guise of providing extra labor. This latter detail explains why such gatherings went ahead. Enslavers often encouraged corn-shucking festivities to speed up the process and at times offered rewards to the person who could shuck the most corn.

The expansion of corn production lies in the decline of tobacco. While tobacco served as the original cash crop of Virginia, its cultivation damaged soils, resulting in increasingly poor crop cycles. Some planters, including George Washington at Mount Vernon, opted to plant grains to avoid this trend and thus have more return each year. As tobacco prices fell in the late 1700s, due in part to the Revolution, more Virginia planters turned their focus to grains. This led to an expansion in corn cultivation, as it became a central part of the economy.

No longer used for just animal feed or local consumption, corn became a cash crop. In doing so, more structures related to grains appeared or underwent expansion. Gristmills became more common as did grain stores near wharfs. On plantations, the land devoted to grains increased to sustain production with additional or larger storage buildings, such as corncribs, appearing to accommodate the harvest. Corncribs would soon rank amongst the most common structures to appear on farmlands. Apart from buildings, husking and shelling additionally underwent a change as this now occurred over the course of a few weeks, thus allowing for enslaved gatherings, rather than throughout the winter.

Corncrib

With corn holding such an important position in society, it required proper storage. Native Americans constructed the first corncribs with Europeans taking note of them shortly after arriving on the continent. The structure evidently held significance for indigenous tribes as many place and group names derive from the various words for a corncrib. Interestingly, our modern term “barbecue” comes from “barbacoa,” an indigenous term from present-day Georgia, which has several meanings including corncrib. Apart from ranging in size, the design of corncribs dating from pre-contact to present appear very similar, as several key elements remain consistent.

The main roles of a corncrib constitute storing harvested corn, protecting it, and keeping it dry. To that end, the most recognizable characteristic involves the floor of the structure resting at least a foot off the ground via posts or piles/piers. Raising the structure deterred vermin from accessing the crop and helped keep it dry. The design of the sides additionally helped with this latter desire as vertical slats or offset horizontal siding provided gaps for airflow. Vertical slats for “cribbing” proved the most common during the colonial period.

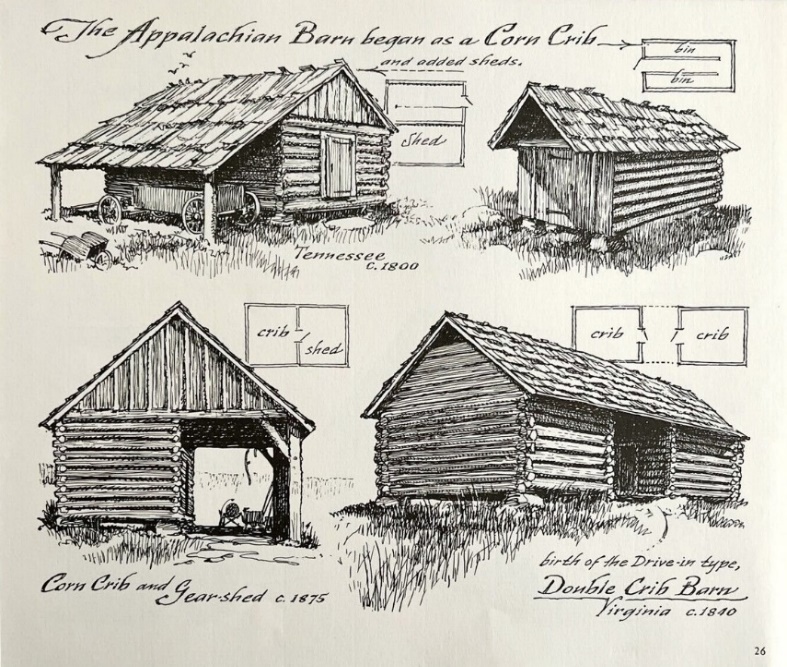

Overall, the structure required robust timbers and construction techniques that would allow it to carry dead loads and resist interior pressure. Once constructed, the building generally took on a rectangular shape with a gabled roof of shingles, boards, or thatch. This roof could extend over one or more sheds attached to the long sides of the building while a door, typically on a shorter side, provided interior access. The interior varied from an open plan to one with removable dividers to form cribs, hence the name of the structure. Post-colonial era designs could include an additional crib to form a double or “drive-thru” corncrib.

Since its adoption by colonists, the building’s name has experienced some variation. While we have gone with “corncrib” at Ferry Farm, several other accurate terms exist. The most simple, and unhelpful for interpreting records, consists of “barn.” During colonial times, “barn” could refer to nearly any outbuilding, and corncribs fall under a barn style called “crib-barns.” This, in turn, may refer to the building. While no standard for outbuildings included on properties existed during this time, corncribs counted amongst the most common. Other name options include the similar “corn-house” and the term “stacks.” This latter term may or may not have “corn” attached to it, but referenced ability to relocate the structure. In the end, unless corn appears in the name, identifying the building requires context clues such as location, crop knowledge, structure design, and recorded narratives.

Our Findings

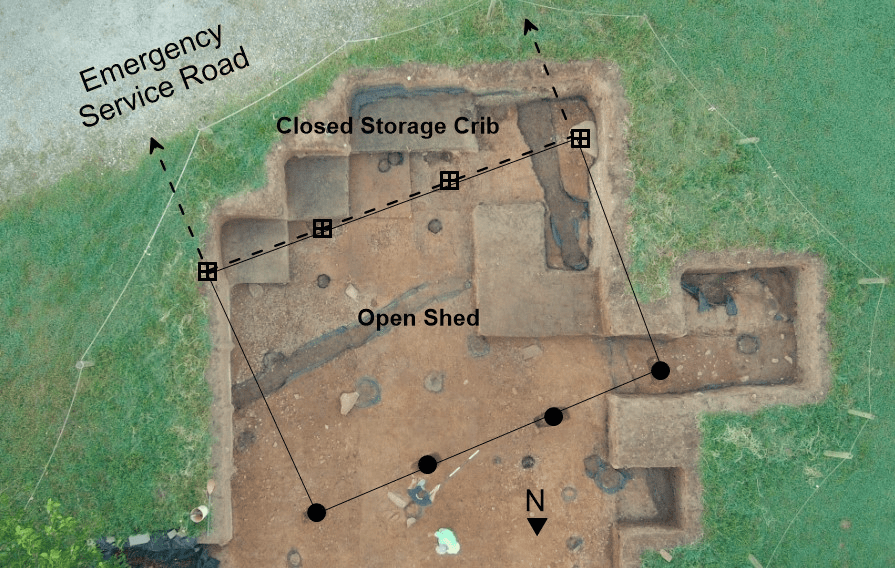

So what did we find to suggest we had a corncrib? To start, we know from documents dating to Washington occupation that corn constituted one of the crops grown at Ferry Farm. We knew little beyond this until archaeology provided an insight. Across our 2020 and 2021 field seasons, we uncovered four aligning postholes that each measured 10ft apart. At the same time, a decline in artifact count occurred, suggesting our dig lay on the outskirts of the work yard. In 2022, we expanded this dig area to determine if the postholes belonged to a fence or, as we hoped, a building. The low artifact count continued to support the theory of entering the agricultural world and we soon discounted a fence line, as our excavation revealed no further postholes on that line. Moving 20ft south from the postholes, we uncovered a line of three features, also 10ft apart, which aligned with the first three postholes. The issue? They came from piles/piers rather than posts, and one of the stones for that line remains in place (Fig. 5).

The two parallel lines evidently went together, but we now needed to identify a structure that used both building techniques. After perusing historic images and sources on 18th century agricultural buildings, we identified the corncrib as the only structure that fit this construction. While corncribs most often stand alone on piles/piers or posts, some examples include an open shed area for carts and temporary storage as discussed earlier. Neither part of the structure would have led to large artifact deposits as the crib merely stored corn while the shed area supported the act of storage.

So what did our corncrib look like? Well, apart from identifying the crib and shed portions, we can say the crib must have rested at least a foot off the ground. Furthermore, in keeping with standard construction, the siding, likely vertical slats, would have breaks in between to allow airflow. As for the basic dimensions of the corncrib, our emergency access road unfortunately runs through the unexcavated portion.

Since we cannot inhibit this access, we only have the complete outline of the shed and one side of the crib (Fig. 6). Still, we can make a few estimates for the structure’s dimensions. While we cannot determine height at this stage, the outline of the shed indicates this portion measured 20x30ft. This, in turn, tells us that the corncrib itself measures 30ft in length. As for the crib’s width, several details allow us to determine a range. One source stated that the length of a corncrib should be 2-3 times the width. Of the examples we identified, they generally had a length about twice the size of the width, with the widest one measuring 20ft. On top of this, shed portions do not appear much wider than the accompanying crib. With this in mind, our crib likely measures 15-20ft in width.

Future

By now, you must wonder when you will see a corncrib at Ferry Farm. One of our goals involves reconstructing the Washington landscape and this will include the corncrib. Currently, we have started construction on a root cellar and slave quarter. Once completed, these structures will be part of your visit and we will turn our attention to reconstructing more areas. This may include the corncrib, but will likely take a few years. In the meantime, continue to visit our ongoing construction projects and make sure to talk with the archaeologists and interpreters.

Historical Fact: Those familiar with the life of Harriet Tubman may recognize the term “corncrib” as she, her brothers, and several others briefly hid in one while she led them to freedom.

Emma Schlauder

Research Archaeologist

Belanger, Fergus & T. H. Warner 1934 Notes about Williamsburg and William and Mary College. The William and Mary Quarterly 14(3): 239-240.

Carson, Cary & Carl Lounsbury (editors) 2013 The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

Carter, Landon 1908 Diary of Col. Landon Carter. The William and Mary Quarterly 16(3): 149-156.

Chandler, Dana 2000 The Prehistory of Randolph County, Alabama. Central States Archaeological Journal 47(1): 28-29.

Copeland, Pamela C. & Richard K MacMaster 1989 The Five George Masons. University of Virginia Press, Richmond, VA.

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway 2023 25. Choptank Landing: Site of Harriet Tubman’s Most Daring Rescues. Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway < https://harriettubmanbyway.org/choptank-landing/>. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Herman, Bernard L. 1992 The Stolen House. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Hollingsworth Jr., G. Dixon 1979 The Story of Barbecue. The Georgia Historical Quarterly 63(3): 391-395.

Katz-Hyman, Martha B. & Kym S. Rice (editors) 2011 World of a Slave: Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the United States. Greenwood, Santa Barbara, CA.

Kimball, Fiske 1954 Gunston Hall. Journal of the Society of American History 13(2): 3-8.

Lanier, Gabrielle M. & Bernard L. Vlach 1997 Everyday Architecture of the Mid-Atlantic: Looking at Buildings and Landscapes. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Linebaugh, Donald W. 1994 “All the Annoyances and Inconveniences of the Country”: Environmental Factors in the Development of Outbuildings in the Colonial Chesapeake. Winterthur Portfolio 29(1): 1-18.

Lounsbury, Carl R. (editor) 1994 An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Morgan, Philip D. 1998 Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake & Lowcountry. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

NPS 2021 Barnyard Trail: Corn Crib. Fire Island National Seashore, NPS <https://www.nps.gov/ places/barnyard-trail-corn-crib.htm>. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Siener, William H. 1985 Charles Yates, the Grain Trade, and Economic Development in Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1750-1810. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 93(4): 409-425.

Sloane, Eric 1990 An Age of Barns, reprint of earlier edition. Henry Holt & Co., New York City, NY.

Speck, Frank G. 1907 Notes on the Chickasaw Ethnology and Folk-Lore. The Journal of American Folklore 20(76): 50-58.

Stilgoe, John R. 1982 Common Landscapes of America, 1580-1845. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Wells, Camille 1993 The Planter’s Prospect: Houses, Outbuildings, and Rural Landscapes in Eighteenth Century Virginia. Winterthur Portfolio 28(1): 1-31.

Upton, Dell & John M. Vlach (editors) 1986 Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture. The University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA.

Vlach, John M. 1993 Back of the Big House: the Architecture of Plantation Slavery. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

Washington, Augustine Jr. 1750 Record of Sale and Payment to Mary Ball Washington.

Washington, George 1749 Letter to Lawrence Washington dated 5 May 1749. Washington Papers, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Washington, George 1771 Survey of Ferry Farm.

Washington, Mary Ball Undated Letter to John Augustine Washington, undated no. 154. Box: 87, Folder: undated no. 154, Identifier: RM-904; MS-5404, The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, VA.