As you drive down the road, sometimes, there are enough signs to make your head spin. It can be tempting to just drive by these stark white cast iron road markers with black text when you see them. Even so, sometimes you can’t help but let a word or a phrase catch your eye, sparking curiosity as you continue on with your travels.

The Virginia Highway Marker program is the oldest one of its kind in the United States (Virginia Department of Transportation, n.d.). In 1927, State Route 1 was freshly paved and ready for new motor vehicles to coast down from Washington, DC to Richmond. (Virginia Department of Transportation, 2006).

Drivers were given a red carpet to travel straight to what many viewed as the birthplace of our nation, George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Thousands began their pilgrimage. Hotels, motels, gas stations, and attractions began to pop up along the path.

With all these new travelers who appreciated their state’s history, William E. Carson of the Conservation and Economic Development Commission erected several markers along the road, designating historic areas of interest and turning the roads into an attraction. (Virginia Department of Transportation, n.d.).

Fabricating the markers was a beast to tackle since the traditional method of construction would have been granite. Unfortunately, the stone was a bit too pricy and was also found to be difficult to read at the lightning-fast 25 mph speed limit. Aluminum was an option for its lightweight and non-corrosive nature, and in fact, many early signs were manufactured from the metal, although they were quickly found to crack easily. They were replaced with cast iron, and cast metal has been the preferred method of construction ever since (Rachal, 1949).

Two of our three markers were first seen in the early years of the program. The oldest of our three was also the one that had the least amount of time in the light. The Accokeek Iron Furnace marker (E-49) is located off Courthouse Rd in Stafford near an archaeological dig site owned by the George Washington Foundation. The modern iteration was erected in 1998.

This text is not what was written prior to 1930. Those signs were brief, containing only a sentence or two for motorists to read as they drove by. Between 1927 and 1930, though, cars sped up. Where they were once going 25 mph, they were soon going 40 mph or even rocketing 50 mph down the highways!

Trying to read the markers while driving quickly became impossible. The Commission’s solution? Publish a booklet with each highway marker printed and arranged neatly for passengers to read as they traveled. All you had to remember was the marker’s number or title. The first of these booklets were distributed in early 1930, free of charge (Rachal, 1949).

This edition contains the earliest record of the Accokeek marker, then titled “Ancient Iron Furnace,” and reading only: “Here on Accokeek Run were iron mines and a furnace in which Augustine Washington, father of George Washington, began to smelt iron in 1727.”

Unfortunately for our little marker, this was the last time it could be featured in the booklet. Disaster struck in late 1930. Engineer P. W. Snead wrote to the Commission on December 19th to report that the sign was found that morning, knocked from its post, and shattered. The commission wrote back a few days later, asking for the aluminum pieces to be gathered and sent back since the factory would refund them for the parts. (Library of Virginia Archives, 1930). The Accokeek marker was not restored until 1998, 68 years later, as part of a federal grant, according to the manager of the highway marker program, Jennifer Loux.

The “Washington’s Boyhood Home” marker is also found in the booklet’s first edition, and its modern counterpart is now at the entrance to Ferry Farm. Although there are no records of the sign being damaged prior to its replacement in 1997, after exposure to the elements for almost 70 years, it was probably time for a refresh.

Alternatively, the motivation for the marker’s replacement (likely from the same federal grant) may have come from historical inaccuracies. The original text of the marker reads:

“Washington’s Boyhood Home: At this place, the Ferry Farm, George Washington lived most of the time from 1739 to 1747. Here, according to tradition, he cut down the cherry tree. Washington’s father died here in 1743. The farm was his share of the paternal estate.”

We now believe that the Cherry Tree story was likely an exaggeration or a myth, and so the verbiage was changed on the modern marker. Many old highway markers contained inaccurate information, as is often the case with many historical resources. As technology and research evolve over time, so does what we know. Another example of this never made it to the press, but early drafts of the marker’s text include his attendance at the “Old Field School.” We have since learned that there is no documentation of Washington ever attending a formal school in his life.

The current marker was installed in 1997, the same year the George Washington Foundation obtained the property, and the sign continues to greet visitors to this day.

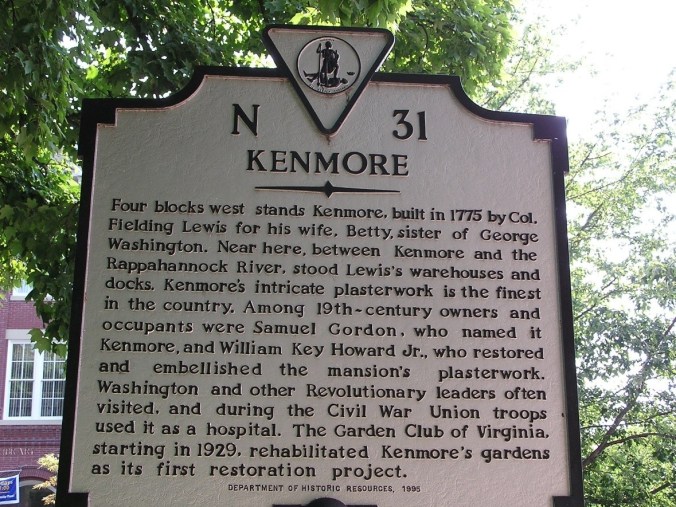

Our third marker is different, having not been placed until 1995. At this point in time, the highway marker program had been passed around, with different organizations all bearing the burden of putting up new signs and maintaining the old ones. It first passed hands in 1949 to the Virginia Department of Highways, who, after a year, handed the responsibility off to the Virginia State Library. In 1966, it was traded again and is now operated by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources in collaboration with the Department of Transportation (Virginia Department of Historic Resources, n.d.).

Former director of the Kenmore Association (now the George Washington Foundation) Vernon Edenfield wrote to the DHR proposing the marker. The Association paid for the manufacturing out of pocket. You can now visit it along Caroline St, four blocks from Kenmore, in front of Fielding Lewis’ storefront.

Although you might think after nearly 100 years of recording and presenting history that the Virginia Highway Marker program has run out of ideas, you can’t be further from the truth. New markers are being planned constantly, and more gaps in history are being filled each year. In Fredericksburg alone, there are plenty more markers commemorating the city’s rich history. If you feel there is an opportunity for a new marker somewhere, you can submit a proposal through the DHR’s website.

History can be found anywhere if you know where to look, and the Virginia highway markers are a testament to that. Be sure to keep an eye out for them on your next drive!

Sarah Alden

Manager of Visitor Services and Interpretation

Bibliography

Laiacona, J. (2021, May 4). Marker Furthers UMW Mission on Freedom Rides’ 60th Anniversary. Retrieved from University of Mary Washington: https://www.umw.edu/news/2021/05/04/marker-furthers-umw-mission-on-freedom-rides-60th-anniversary/

Library of Virginia Archives. (1930). Virginia

Mount Vernon. (n.d.). Historic Preservation at Mount Vernon. Retrieved from George Washington’s Mount Vernon: https://www.mountvernon.org/preservation/historic-preservation-at-mount-vernon#main-content

Prats, J. J. (2010, October 23). State Historical Markers Numbering Plans. Retrieved from The Historical marker Database: https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=2

Rachal, W. M. (1949). Historical Markers on Virginia Highways. State and Local History News, 151-153.

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. (n.d.). Historic Markers. Retrieved from Virginia Department of Historic Resources: https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/programs/highway-markers/

Virginia Department of Transportation. (2006). A History of Roads in Virginia: “The Most Convenient Wayes”. Richmond: Virginia Department of Transportation Office of Public Affairs.

Virginia Department of Transportation. (n.d.). Historical Markers. Retrieved from Directional Signing Program: https://vaidsp.com/historicalmarkers/

Virginia State Chamber of Commerce, a. L. (n.d.). Highway markers near Seven Pines, Va. Picture Collection.