Archaeologists tend to have strong feelings about ceramics. Ceramics can play a major role in interpreting a site, as their materials often reflect their function. This can be helpful when determining how a site was used. For instance, finding an abundance of redwares and stonewares could indicate a primarily utilitarian site like what would have been used in our Cellar House whereas porcelain and refined earthenwares may reflect a more domestic space. So, it really isn’t surprising that we feel some type of way about these artifacts.

But don’t let that fool you. Archaeologists have feelings about ceramics based solely on their appearance as well. It has come to my attention that Whieldon Ware just might hold the title as the most polarizing ceramic type as of late. These feelings were made very apparent during our recent acquisition of some Whieldon Ware pieces. Most either love or hate it; rarely is there an in-between. Before we get into the ceramic and its distinct look that conjures images of either vomit or a work of art (depending on whom you ask), let’s go over a little background on its creator, Thomas Whieldon.

Thomas Whieldon was an influential English potter producing examples of early creamware beginning in the mid-18th century. He gained popularity for his innovative shapes and decoration, which can be seen on various figurines, dishes, and other vessels. Whieldon is also well known for his partnership with the MVP of the ceramics world, Josiah Wedgwood, Mr. Creamware himself. Together, they developed advances in the realm of refined earthenware, like the perfecting of the green glaze as seen on the pineappleware we have found at Ferry Farm (Wedgwood & Ormsbee, 1947).

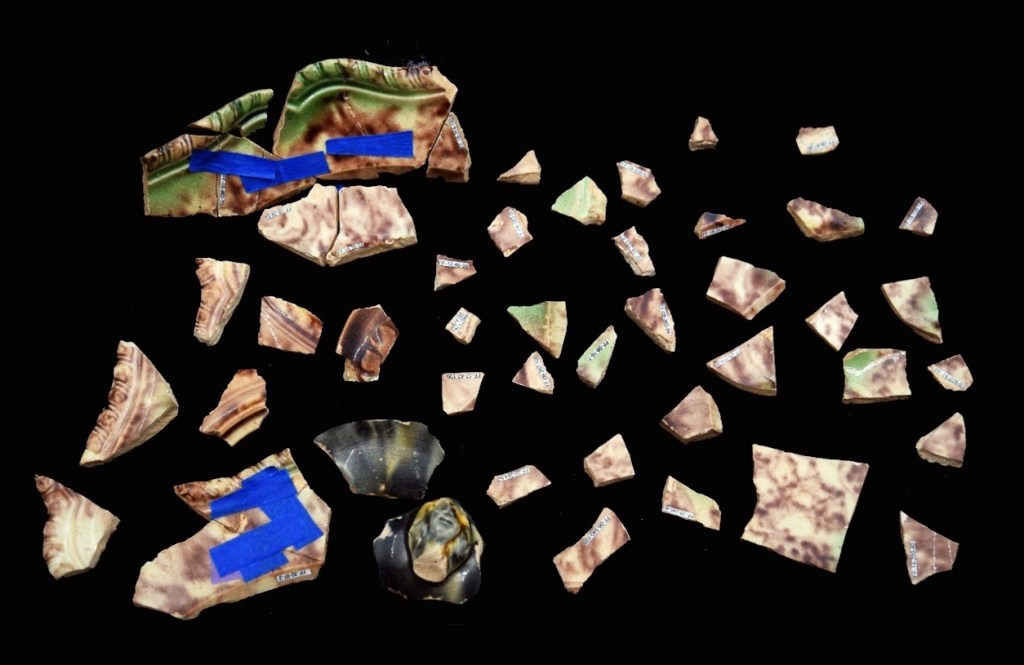

With that said, what we commonly think of when referring to Whieldon Ware is Whieldon’s tortoiseshell or clouded wares. These were created by sponging metal oxides on cream-colored earthenware and then adding a clear lead glaze. The mixing of the metal oxides with the liquid glaze caused the colors to blend and streak, creating splotches of green, yellow, purple, blue, and brown, depending on the types of metal oxides used (Gallagher, 2015). This resulted in a clouded or tortoiseshell decoration. Due to the nature of the technique, no two pieces look exactly the same. For Whieldon lovers like myself, the uniqueness of each piece gives it its charm.

Now that we know more about Whieldon Ware and how some of us feel about it today, let’s talk about how Mary Washington may have felt about it. I firmly believe that she was not team Vomit Ware and instead found the decoration quite desirable. Our excavations have found evidence of at least four Whieldon Ware plates, a teapot, teacup, and other medium-sized holloware vessels at Ferry Farm. Considering the short-lived popularity of the type, lasting only from 1740-1775, we can be quite certain that it was Mary who was buying these items.

Toward the end of the 1770’s, Whieldon Ware quickly went out of style and was replaced by Wedgwood’s new, improved creamware and its more subtle decoration. While it may have gone out of style, potters continued to replicate the technique for many years, which makes it difficult to attribute all examples of the type to Whieldon himself. After 1780, he retired from the business, demolished his factory, built an ornamental garden in its place, and spent the rest of his years as a sheriff (Hildyard, 2005; The London Gazette, 1785).

So, there you have it, the very brief story of Whieldon and his wares.

While Mary Washington and a couple of us in the lab are Team Whieldon all day, every day (or at least the days concerning Whieldon), the majority are a hard pass. Where do you stand? Are you Team Whieldon or team Whieldout?

Danielle Arens

GWF Archaeologist

References

Gallagher, B. (2015). British Ceramics 1675-1825: The Mint Museum. Charlotte: The Mint Museum.

Hildyard, R. (2005). English Pottery 1620-1840. London: V&A Publications.

The London Gazette. (1785, November 12). The London Gazette(12699), p. 522.

Wedgwood, J., & Ormsbee, T. H. (1947). Staffordshire Pottery. New York: Robert M. McBride & Company.

Images

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1938-0314-47-CR – figurine

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1923-0122-13-CR – coffee pot

https://vandekar.com/inventory/Ceramics/British%20Pottery/Whieldon/works/26486 – tea pot