While the house at Historic Kenmore has been faithfully restored to its circa 1775 appearance, the road to that final result was a pretty dirty one. As in plaster dust, paint fumes, and all manner of dirt and debris. Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the first forays into the research for and the subsequent writing of a Historic Structure Report (HSR) took place. This project entailed a number of architectural historians selectively pulling up floorboards and peeking behind plaster walls to more fully understand how the house was originally built, its current condition, and its history of change over time. This important document provided us with a clear understanding of Kenmore’s architectural history, was the guiding document for a decade-long restoration of the structure, and also gave us a collection of architectural fragments and individual artifact finds that continue to help us understand the material world of those who lived and labored at Kenmore through the centuries.

In a past blog post, we learned a bit about rats as collectors and examined a rat’s nest that was discovered during that HSR investigative period. If you haven’t looked at the video of the unpacking of that nest, here it is. (In that nest, there were assorted papers, fibers, and other fluffy goodies dating to around the turn of the 20th century.) But the nest wasn’t the only thing uncovered during that HSR peeking and prodding process.

Of Mice and Men: A brief exploration of rodents’ history in America

The Unlikely Curator: What a Rodent’s Nest Reveals about Historic Kenmore

Enter the “Above Ground Archaeology” or “Interior Archaeology” collection. These eclectic artifacts were carefully collected, numbered according to their context or find location, bagged, documented on a list, and lovingly packed away in our ubiquitous Hollinger boxes. Over the years, some of the artifacts were pulled by curators for exhibition in the Kenmore galleries, but most were stowed away in their boxes for long-term preservation and research purposes.

The use of found objects in historic structures to help illuminate the material world of the building’s residents and workers is not a revolutionary concept. Colonial Williamsburg, for instance, in their recent restoration of the historic Bray School, removed modern plaster walls, revealing not only structural information but also artifacts: “We are collecting building fragments and objects found in the walls…These items shed light on the building’s original finishes and various inhabitants since 1760.” Riversdale Historical Society has been showcasing some of their “found” artifacts on Facebook — most recently posting a set of buttons for National Button Day.

Colonial Williamsburg: The Bray School Project

Riversdale Historical Society, Facebook Post, 16 November 2024

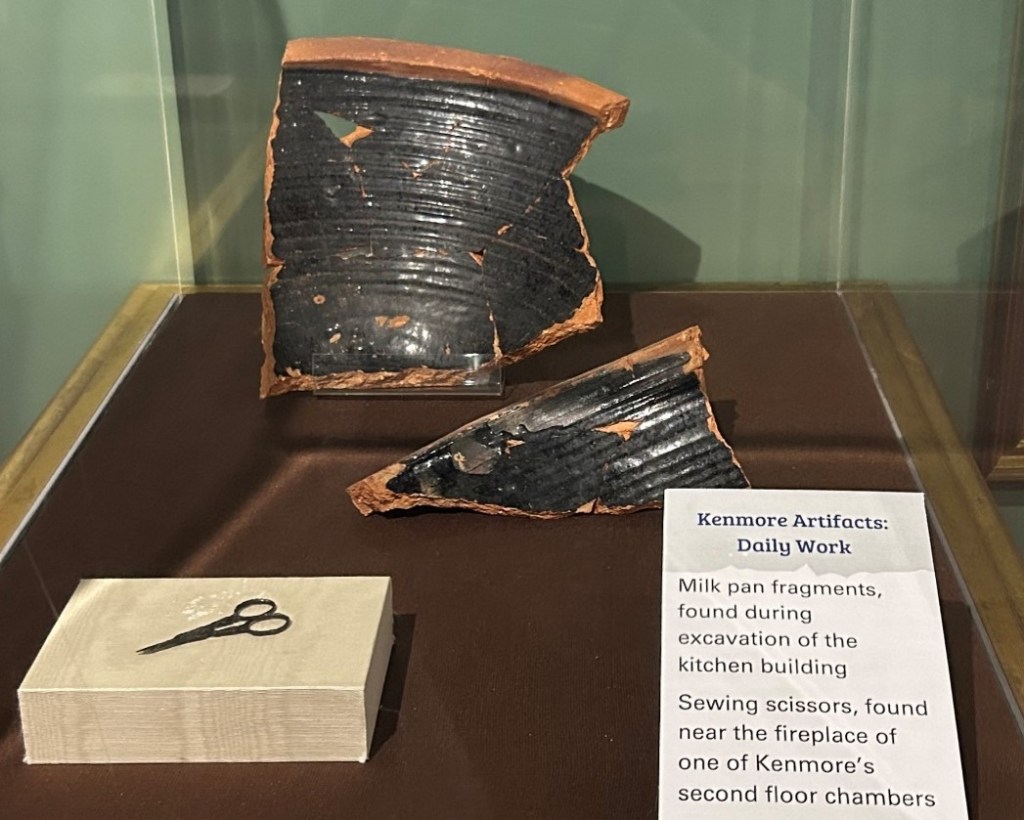

Recently, we pulled a few of Kenmore’s artifacts into exhibit cases in our refreshed orientation exhibit in the Bissell Gallery of the Crowninshield Education Center at Historic Kenmore. Together with in-ground archaeology, these exhibit cases help us illustrate the built environment and the wares known and used at the site.

In 2010, then Intern Ashley Dean (University of Mary Washington) was tasked with inventorying the three boxes of artifacts, and for that, we are extremely grateful. What resulted from that inventory project was a 12-page list of artifacts that formed the center of this rejuvenated research initiative. The artifacts in these boxes range from architectural elements (plaster fragments, nails, wallpaper bits) to broken household goods (bottle glass, ceramic pieces) to whole objects (beads and a pair of sewing scissors). When first bagged and numbered, these artifacts were recorded by location context—based on the mapping system then being used in the architectural investigations of the house, with room numbers ranging from B001 in the cellar (or basement level) to 301 being the attic (or 3rd floor) of the house.

Fast forward to 2024, the artifacts were again reviewed, and the idea blossomed to plan a textile assessment of all the small scraps of fabrics that had been collected. According to our in-house review, we could tell that they dated to a variety of periods and ranged in their likely original use, from costumes to household linens.

One particularly large artifact proved the most intriguing — a pile of blue and white check fabric. The indeterminate ball of checked fabric piqued the interest of staff and now serves as the starting point for a multi-year conservation assessment and interpretation project. A few months after our in-house assessment, we hosted a textile conservator who conducted a baseline review of the textile fragments and more fully examined the artifact for potential treatment. She had a rapt audience that morning!

And just a few weeks ago, the textile artifact, which looks to be a full child’s apron or pinafore, was transported to the conservation lab for treatment and further research.

The found artifacts from Historic Kenmore have not yet been able to fully share their stories. We look forward to beginning to delve more into their manufacture, use, and re-use by the generations of people who wore them, worked with them, saved them, hid them, and otherwise interacted with the artifacts and the spaces in which they were found.

Gretchen Pendleton

Aldrich Director of Curatorial Operations