Thanksgiving is next week, and families and friends across the United States will gather again to celebrate the past year’s blessings.

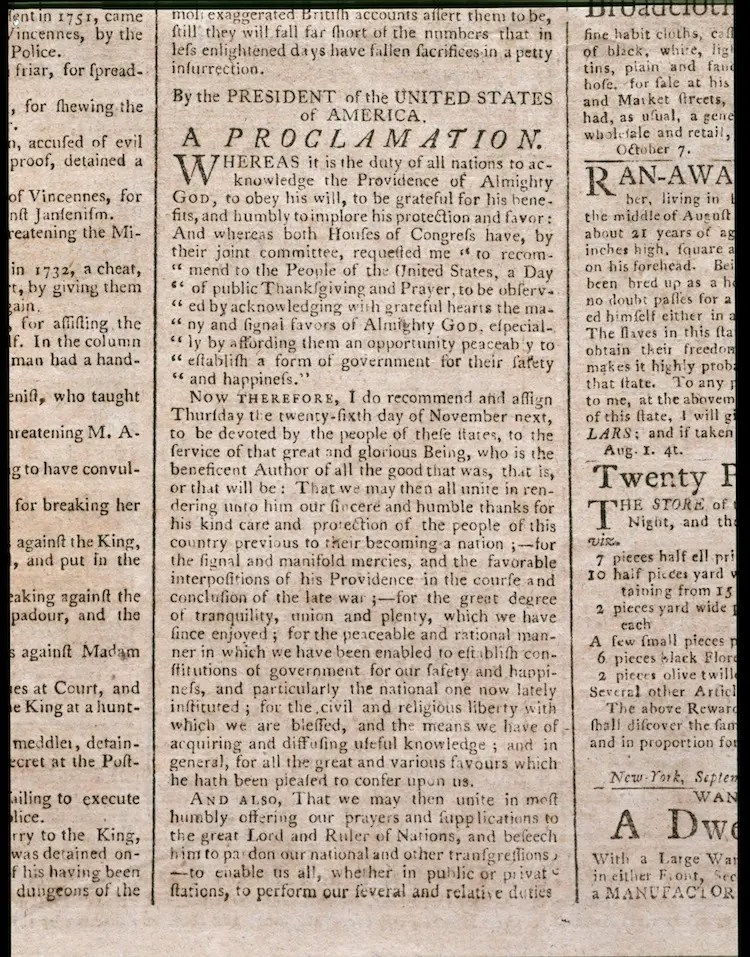

Days for giving thanks have been proclaimed throughout history for many reasons – most often to celebrate a bountiful summer or fall harvest, the end of a war, or even the beginning of a new nation. George Washington proclaimed a one-time day of Thanksgiving on Thursday, November 26, 1789, “to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, … for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed, and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.”.

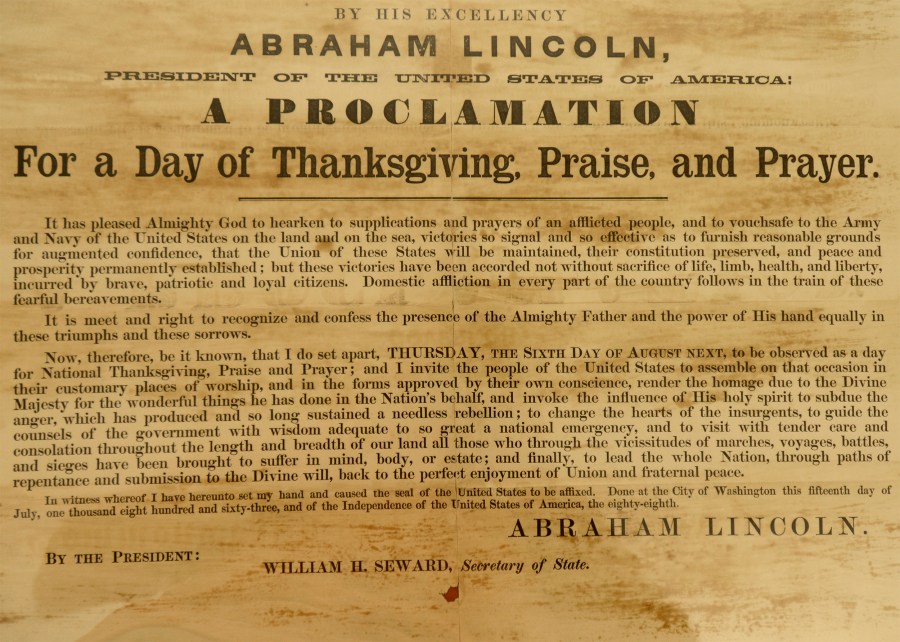

Individual states have proclaimed specific Thanksgiving days throughout the nation’s early years. Still, it wasn’t until 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation designating the last Thursday of November “as a day of Thanksgiving” to be observed by all “fellow citizens in every part of the United States.” The nation was still suffering through the Civil War. Lincoln included a remembrance of “all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity, and Union.”

As the traditional vision of Thanksgiving is based upon the 1621 New England harvest feast shared by the Pilgrims of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and their new friends, the Wampanoag tribe, the November holiday is associated with an abundance and display of fall harvest foods. A table laden with a wide spread of traditional foodstuffs is the norm, but what’s underneath all that food is what I’m interested in!

Our best china! Sometimes, it’s Grandma’s china, brought out of the basement, dusted, and cleaned off for the occasion. Other times, it’s our wedding china, if you are of that generation that still wants or received wedding china. Other times, it’s unique dishes made and decorated for the occasion (think turkey-shaped plates!). Dinner plates, salad and butter plates, serving platters and bowls, condiment vessels, punch bowls, sauceboats for the gravy, dessert plates, tea, and coffee services, crustal wine glasses – the variety can be tremendous, and the different table wares are utilized to display and serve specific foods and finished dishes.

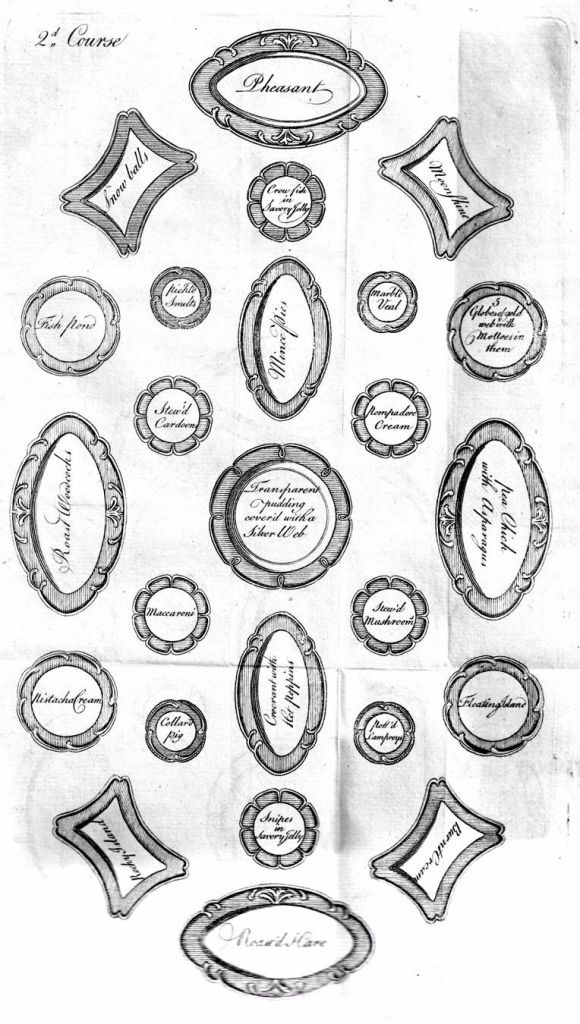

Mary Washington, as a member of the gentry class in Colonial Virginia, would have been well-versed in setting a stylish dinner table for family and guests. Formal dining habits during the 18th century slowly evolved to dinners consisting of multiple courses of food prepared and served in a more elaborate and complicated fashion. Cookbooks of the age detailed the possible menus for different seasons and even produced drawings of how each course’s dishes were laid out on the table. Elizabeth Rafferty’s 1769 The Experienced English Housekeeper includes a copperplate drawing illustrating one such arrangement for the second course of a dinner. Hours could be spent looking up how some of her dishes were prepared, such as “Pistacha Cream,” “Potted Lampreys,” or “Transparent Pudding Covered With a Silver Web.”

Fragments of highly specialized ceramics excavated at Ferry Farm, the plantation Mary called home for much of her life, speak to her efforts to set a stylish table for guests. Numerous highly decorated (molded or painted) creamware vessels, including sauceboats, plates, platters, oval and round serving bowls, condiment bowls, casters, serving spoons, and tea wares, are in our collection and speak to the refinement of her table. Porcelain was the most desirous of tablewares, but its sheer expense was prohibitive for Mary except for limited items, such as teawares. Creamware, however, was within her budget and was extremely fashionable during the third quarter of the eighteenth century in English society.

Mary also had a fancy white salt-glazed stoneware fruit dish in her collection. This dish, and possibly an accompanying pierced bowl, would serve local and non-local produce such as grapes, figs, oranges, pineapples, apples, peaches, and pears. Fresh fruit, especially during off-season times, was expensive as it had to be shipped in from warmer climates. However, its presence on the table indicated a measure of wealth and, consequently, status within the gentry lifestyle. Mary needed to maintain her gentry status for herself, but more importantly, for her children and their future success in the stratified society in which they lived.

So, what’s on your table this Thanksgiving?

Judy Jobrack

Archaeology Field Director