Think about a portrait or painting of George Washington. What is a common element in the paintings? His uniform, yes, he is indeed painted quite a bit in his impressive military uniform. But how about a horse? George is often painted riding beautiful horses with a quiet dignity and noble appearance we expect from the father of our country.

However, the horses in these paintings are not mere symbols of wealth or power. They are depicted with George because, from a tender age, his life has been intertwined with these creatures. As a surveyor, soldier, landowner, farmer, gentry, commander-in-chief, and president, he was inextricably linked with horses, not just as a mode of transportation but as a vital part of his daily life.

And it all started at Ferry Farm…

George moved to Ferry Farm around 1738 at the age of six. His father, Augustine Washington, was a member of the “planter class,” or Colonial American gentry. This meant he was a prominent member of society, involved in politics, and owned lots of land. Augustine purchased 150 acres across the river from Fredericksburg and later added an additional 450-acre parcel. In total, he owned Little Hunting Creek, Pope’s Creek, and the Ferry Farm properties.

The point? Augustine needed help because there were places to be, people to see, and fields to farm. So, horses were a fundamental necessity for the Washington family, and George would have grown up around them, taking care of them and learning to ride.

We have two great sources that give us some understanding of the horse situation at Ferry Farm. First, in 1743, the Washington patriarch died, leaving behind a widow, an 11-year-old George, and a probate inventory. On page two of the inventory, three horses and one mare are listed.

Secondly, some pretty cool horse tack dating from the Washington occupation has been found during various archeological digs.

The Finds

One of the most universally known horse tack, essential for all horse maintenance – is the horseshoe. The horseshoe was used to protect the hooves because “…being rendered subservient to the use of man…applied to severe and continued labour, and compelled to tread frequently…on the irregular and stony surface of the roads, it became necessary to secure his feet from ruin by strengthening them with the iron band which we call a shoe” (Vial de Saint Bel, 1793). These shoes were handmade with no standardization across makers in shape, narrowness, or thickness. (Hume, 2001). This makes it difficult to pinpoint and assign a time on shape alone.

Our horseshoe was found in the second cellar of the Washington Home. It is quite wide between the branches (the curving sides), and the toe seems to straighten a bit at the center. The crease (the groove that runs down the sides) gives enough depth to allow the shoe to be firmly attached to the hoof with six nails (which we found a few originals). (University of Zurich, 2024) This find illustrates that there was active shoeing and horse maintenance going on at the farm. Additionally, these horses were ridden or used for farm work because shoes were used to protect the hooves from the wear and tear of hard roads, distribute the horse’s weight evenly on uneven ground, and provide traction on various surfaces.

Another artifact found in the cellar of the Washington Home, the stirrup, further demonstrates horse riding as a family necessity. (Cofield, 2014)

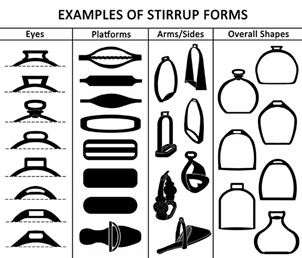

The stirrups are used as foot support for the rider, and they hang from a saddle on straps known as stirrup leathers. Basic stirrups are made of three parts the eyes for the stirrup leathers to attach the stirrup to the saddle, a platform or base where the rider places their foot, and arms which connect the eye to the base. (Cofield, 2014)

Horseback riding master and author VS Littauer described the Forward Seat as a stirrup-centric approach versus traditional riding’s seat-centric. He argued riding without stirrups taught people to grip with the knee, which he considered a dangerous habit and likely to stiffen the rider. With stirrups, you can ride with a looser knee, letting your weight flow PAST your knee and into the stirrup. That is a more secure approach than riding with the thigh and knee. (Littauer, 1962)

Stirrups allow the rider’s legs to absorb up/down motion by allowing them to stand in matching balance with the horse, which makes riding longer distances more comfortable. Augustine certainly had to travel a great distance to check on his properties and perform his civic duties, like serving as a justice of the peace and sheriff for the county of Westmoreland.

One final utilitarian bit of horse tack found again in the cellar is a mullen mouth bit or snaffle bit. This bit consists of two rings on each side of a half-moon-shaped bar with no joint. The bit applies even pressure on the horse’s tongue and bars (gums) and allows the horse’s lips to feel the pressure from the bit and side rings. The bit, bridle, and reins function to create communication between the rider and the horse.

The Washington children would have used bits to learn to control. They would have learned how to work with the horse in a cooperative way that would create an effortless and seamless ride. George used this skill of communication and intuition to become a great rider. As Thomas Jefferson reminisced in a letter in 1814, “his person, you know, was fine, his stature exactly what one would wish, his deportment easy, erect, and noble; the best horseman of his age, and the most graceful figure that could be seen on horseback.” (National Archives, n.d.)

Lastly, just south of “The Quarter,” we uncovered around twenty leather ornaments. They were used to decorate the leather straps, nosebands, harnesses, and reins of horses. We wrote a post about them earlier explaining their purpose, which was purely aesthetic. Horse tack could be made without these pieces, but where is the fun in that? These flashy accessories were a great way to grab the attention of the public and hint at how fashionable and elegant you were as you trotted through town.

These artifacts illustrate that not only were horses actively used by the family, but it also fostered an environment where young George would have taken his first steps into learning about horsemanship. This knowledge and skill would help him in his future careers of surveying the Shenandoah Valley, as a lieutenant colonel during the French and Indian War, as a farmer and landowner at Mount Vernon, as a representative in the House of Burgesses, as commander-and-chief of the Continental Army and finally President of the United States.

Come see our new pop-up exhibit at Ferry Farm, where all these wonderful artifacts are displayed and put together with the help of our Fleming-Smith scholar, Sarah Moore.

References

Cofield, S. R. (2014, May 14). Stirrups. Retrieved from Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland: https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/SmallFinds/Stirrups/index-stirrups.html

Hume, I. N. (2001). A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. New York: Vintage Books.

Littauer, V. S. (1962). The Development of Modern Riding. Washington D.C.: D.Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

National Archives. (n.d.). Thomas Jefferson to Walter Jones, 2 January 1814. Retrieved from Founders Online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-07-02-0052

University of Zurich. (2024). Fullering. Retrieved from E-Hoof: https://e-hoof.com/glossary/en/fullering/

Vial de Saint Bel, C. (1793). Lectures on the Elements of Farriery. London: Veterinary College, London.