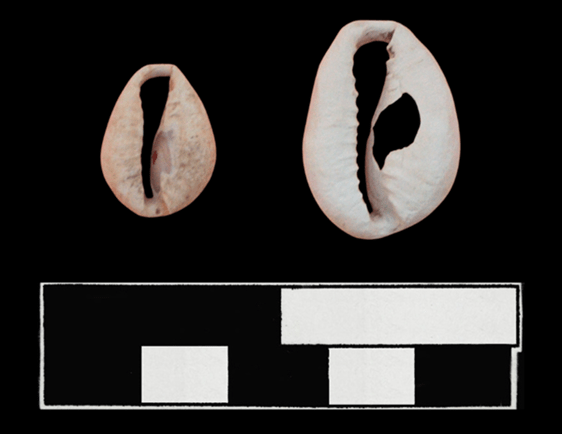

Many readers will undoubtedly recognize these two artifacts (Fig. 1). Known as cowrie shells, these artifacts have become synonymous with slavery and serve as identifiers for the presence of free and enslaved Black individuals in the Americas. Still, the role of cowries in the 18th century goes far beyond that of a marker.

Origin

Cowries (Cypraeidae), a taxonomic family of sea snail, live throughout the world (Fig. 2). However, the species with the most relevance to the 1700s reside in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in the waters around the Maldives. They include Monetaria annulus (alt. Cypraea annulus, Annulus Linnaeus) and Monetaria moneta (Fig. 3). Even if your Latin proves non-existent, each species’ genus, along with M. moneta’s epithet, easily identifies the original role cowries played in human hands – money.

Barabara Heath

Economics and Culture in West Africa

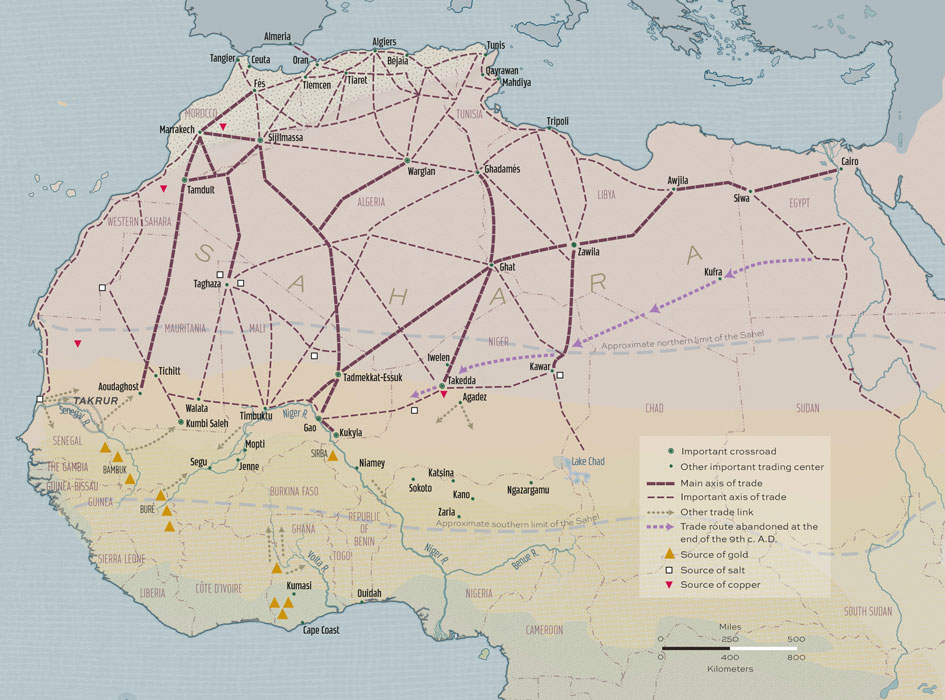

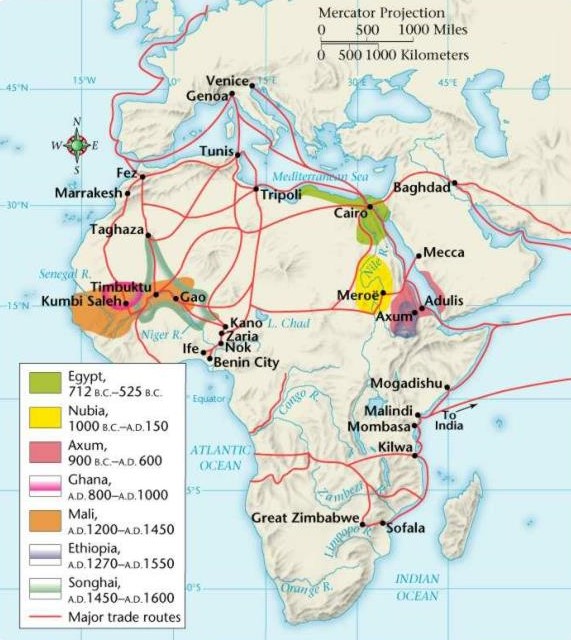

Centuries before the 1700s, West Africa thrived as a region of independent kingdoms and tribes. With these groups engaged in trade, they required a shared currency that served as a medium of exchange and a store of value. In choosing cowries as currency in the fourteenth century, West Africa continued a long history of groups throughout the world using shell money. Through pre-existing trade routes to the Indo-Pacific, West Africans could easily import the shells via other parts of Africa and had them transported across the Sahara. As the cowries used did not reside in West Africa and proved difficult to forge, the market had built in protections against hyperinflation and counterfeits.

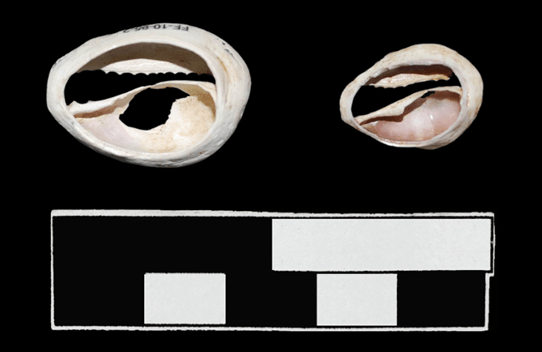

Once in West Africa, the shells served as the basis of the region’s economies. Still, the shells took on several cultural roles. To keep cowries on hand, the shells often underwent modifications, including slicing off the rounded side of the shell or piercing them (Fig. 4). This allowed for stringing them together and weaving into hair or onto clothing. While done for practical reasons, this led cowries to enter the world of personal adornment. With this, their role expanded to symbols of status, fertility, and beauty while further appearing on ceremonial garb (Fig. 5).

British Museum

Atlantic Trade Routes

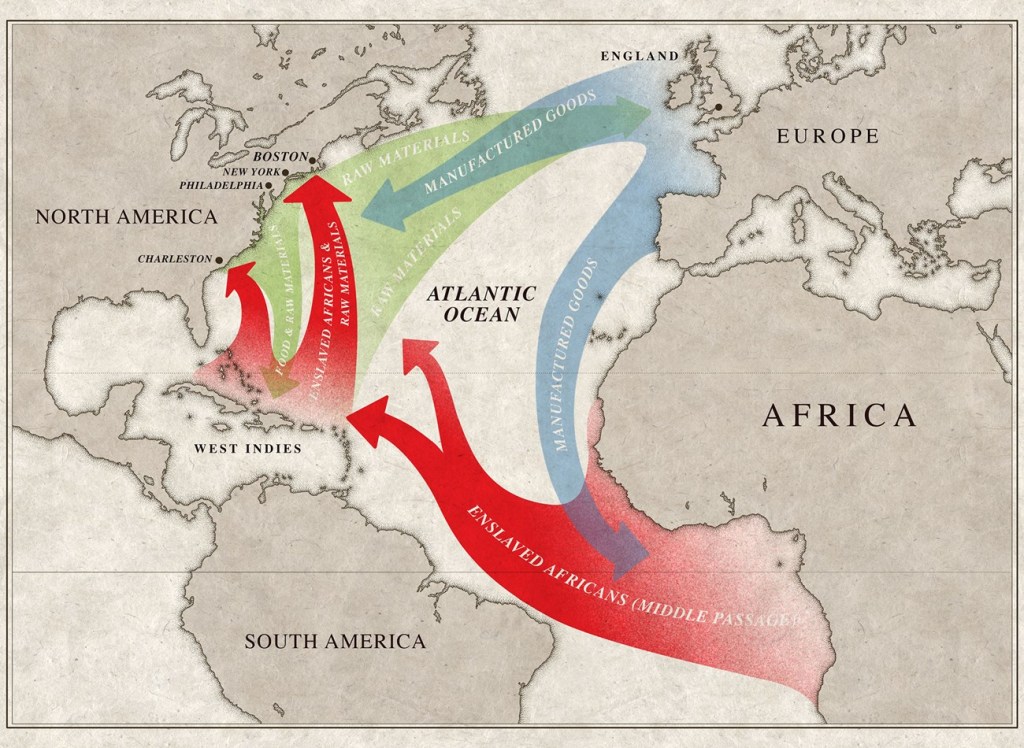

Europe and Africa had a long history of trade and exchange networks prior to the late 1400s, but the boom of global exploration led to an immediate escalation of these market connections. With European nations expanding their territories abroad and seeking to gain resources not found within their borders, they developed a need to break into the African markets while establishing permanent trade posts in the region. To achieve this, Europeans needed to supply goods that were in demand, and their minds set upon cowries.

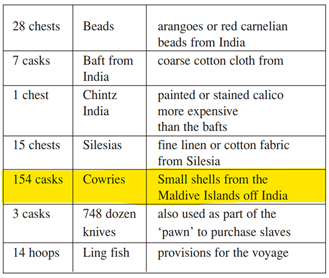

While an item of currency and self-adornment to West Africans, cowries became a commodity in the hands of European, and later American, merchants. With cowries, merchants could navigate the local economy and barter for desired goods. Inevitably, this included kidnapped Africans. In his memoir, Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745-1797), a famed writer and abolitionist, recalled how one enslaver sold him to another for 172 “little white shells” while still in Africa. An examination of eighteenth-century shipping records reveals that cowries ranked amongst the most common goods transported to West Africa and used to trade for captives (Fig 6). For Africans who then faced the Middle Passage, they forcibly traveled aboard these same ships that in turn provided West Africa with the currency driving the economy and their enslavement — cowries.

Manx National Heritage

Cowries in the Americas

Indo-Pacific cowries arrived in the Americas through several carriers, but ultimately all traveled on slave ships. In trading cowries to West Africa, foreign merchants supplied both types even though the market preferred M. moneta. As such, they often had leftover M. annulus which remained onboard as cargo and ballast when the ships continued their trans-Atlantic journeys. Once in the Americas, some captains elected to dump or sell off the remaining cowries rather than transport them back across the Atlantic. Cowries additionally arrived in the Americas on the bodies of kidnapped Africans. While common practice involved stripping captives in Africa, primary accounts report individuals retained beads and shells in their hair and as necklaces. Enslavers further distributed beads, and likely shells, as pacifiers during the Middle Passage.

Once in the Americas, cowries largely remained within Black communities though they did face geographical restrictions. For Virginia, archaeological distribution of the shells, mainly M. annulus, places them within the Tidewater region. Higher counts of shells appear in urban areas (Yorktown = 252) while plantations typically only have a few. Although Virginia’s current archaeological cowrie count falls above 353, this remains too few to support the traditional role as currency. Instead, the shells continued in roles of adornment and ritual with added symbolism of cultural loss, memory, and survival. Outside random finds in areas associated with enslavement, cowries recovered in the Americas have derived from burials, spirit caches, and sub-floor pits (Fig. 7).

At Ferry Farm

Over the course of our twenty-plus year excavation, two cowries have appeared at Ferry Farm. Found in contexts located around the Washington House, including one in a root cellar, our shells represent M. annulus and have undergone modification to allow for stringing or weaving (Fig. 8). As with findings in previous studies, we believe these shells took on cultural roles through self-adornment. Despite not knowing the identity of the shells’ owner(s), the cowries provide enough information to form an interpretation of who they belonged to and how they arrived at Ferry Farm.

As their contexts of origin line up with the Washington House, the enslaved individuals who left them behind likely lived and worked close to the Washington family. This places them within the working realm of the house or the nearby work yard. For accommodation, the owner(s) may have occupied the Quarter adjacent to the Washington house or lived in one of the work yard’s support buildings.

Regarding the arrival of cowries on the plantation, this likely happened through the movement and exchange of people and goods. To provide the labor required to meet their goals, enslavers moved those they enslaved between different plantations as needed and expanded their workforce through the enslavement of more people or hiring of persons enslaved by others. This could account for the arrival of cowries at Ferry Farm. Alternatively, Ferry Farm’s proximity to the (port) city of Fredericksburg meant the enslaved community had access to a regional economy and trans-Atlantic vessels. Either network may have transported cowries to the city, but it additionally meant that Fredericksburg served as a meeting and trade point for those enslaved in the region.

Legacy

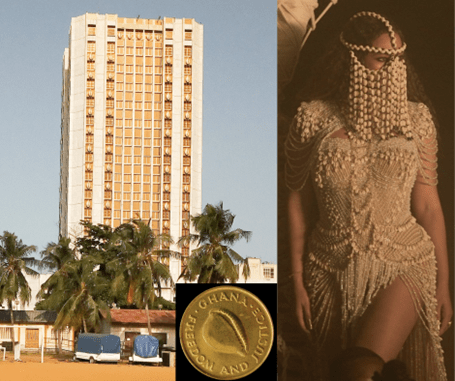

Cowries have a long and nuanced history in the Atlantic World. Beginning as a unit of currency and cultural symbol, cowries fell prey to the demands of the market, taking on a new role in the hands of foreign merchants. What once served to strengthen economies and nations suddenly worked to strip away the very people who inhabited West Africa. For those who endured enslavement, the cowries that accompanied them became symbols of a stolen home, a continuation of culture, and a determination to survive. Today, cowries remain important items in African and African American cultures by symbolizing their history as currency, continuing in self-adornment and ritual roles, and appearing prominently in works of art (Fig. 9-11).

Right: Beyoncé donning a cowrie headdress by Ivorian designer Lafalaise Dion Design Indaba

Emma Schlauder

Research Archaeologist

Bibliography

Alpern, Stanley B. 1995 What Africans Got for Their Slaves: A Master List of European Trade Goods. History in Africa 22: 5-43

Equiano, Olaudah 1789 The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African. Written By Himself. London, UK

Handler, Jerome S. 2006 On the Transportation of Material Goods by Enslaved Africans During the Middle Passage: Preliminary findings from Documentary Sources. African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter 9 (4): 1-22 (Article 16).

2007 From Cambay in India to Barbados in the Caribbean: Two Unique Beads from a Plantation Slave Cemetery. African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter 10(1): 1-10 (Article 1)

Heath, Barbara J. 2016 Cowrie Shells, Global Trade, and Local Exchange: Piecing Together the Evidence for Colonial Virginia. Historical Archaeology 50 (2): 17-46.

National Museum of African American History & Culture n.d. Cowrie Shells and Trade Power. National Museum of African American History & Culture, Smithsonian, Washington D.C. <https://nmaahc.si.edu/cowrie-shells-and-trade-power>. Accessed 3 June 2024.

Ogundiran, Akinwumi 2002 Of Small Things Remembered: Beads, Cowries, and Cultural Translations of the Atlantic Experience in Yorubaland. The International Journal of African Historical Studies 35 (2/3): 427-457.

Pallaver, Karin 2023 Cowries, the currency that powered West Africa. ReThink Quarterly 7 <https://rethinkq.adp.com/artifact-cowries-west-africa/>. Accessed 3 June 2024.

Pearce, Laurie E. 1992 The Cowrie Shell in Virginia: A Critical Evaluation of Potential Archaeological Significance. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, College of William & Mary. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Radburn, Nicholas J. 2009 William Davenport, the Slave Trade, and Merchant Enterprise in Eighteenth-Century Liverpool. Master’s thesis, Department of History, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Samford, Patricia 1994 Searching for West African Cultural Meanings in the Archaeological Record. African Diaspora Newsletter 1 (3): 1-3 (Article 2).