A Personal Look At Civil War Soldiers As Told Through Artifacts

Ferry Farm is most well-known as the Boyhood home of George Washington. While our primary emphasis of interpretation and research has focused on young George and his family’s life on this farm, Ferry Farm has many other stories to tell. The American Civil War had a major impact on the Ferry Farm community, changing both the landscape and the lives of those who lived here. This blog will look at how our archaeological efforts have brought to light artifacts that reflect the experiences of the soldiers that were stationed on the “old Washington Farm.”

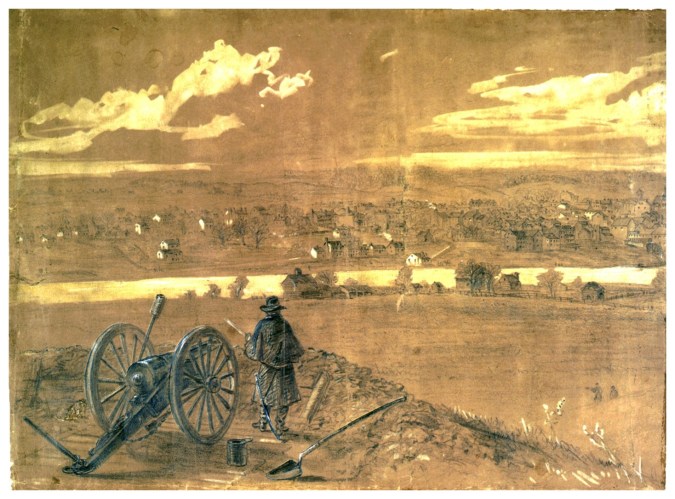

The Washington house and its outbuildings gradually fell into disrepair until by the mid-1830s there was no trace of them on the landscape. But the soldiers still knew the significance of the site. In April 1862, the Civil War came full force to Fredericksburg and to Ferry Farm. Federal Forces took over and occupied the City of Fredericksburg behind the retreating Confederate Army. Encampments and gun emplacements were established all along our side of the river and throughout Stafford County as the army set about maintaining control of the city across the river. Engineers were set to the task of rebuilding the railroad bridge and erecting pontoon bridges, including one at the end of Ferry Road.

This spring deployment and the military occupation of Ferry Farm was relatively quiet and uneventful. There is no evidence of a large, formal camp at Ferry Farm, but soldiers were stationed here to protect one of the pontoon bridges that ran from the bottom land of Ferry Farm across to the city of Fredericksburg. In August of 1862, the army suddenly retreated from the city and the surrounding countryside to defend Washington, D.C.

In November of the same year, the full force of the Union Army returned to Stafford County in preparation for the retaking of Fredericksburg and their expected march to take over Richmond. Instead, the Federals suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December and retreated to the north side of the river for winter camp. Now, Ferry Farm was being used more actively as a staging ground for multiple troop movements, bivouacs for soldiers guarding the pontoon bridges, and as a defensive line for the Federal troops.

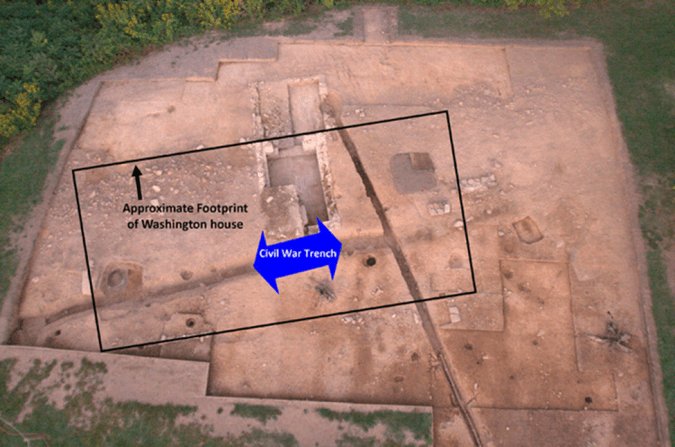

A defensive trench, or rifle pit, with an adjoining berm to protect soldiers from gunfire originating on the Fredericksburg side of the river, was dug across the edge of the upper river terrace, stretching north-south from the edge of the stream gully through the remains of the Washington house. A small extension on the south end of the trench was dug out to connect it to the now-exposed cellar.

Artifacts found within the cellar trench fill reflect the extensive use of the house ruins by soldiers during both occupations. In the spring and summer, they used the farmhouse as their headquarters, writing on the plaster walls and leaving graffiti in pencil and charcoal on hundreds of plaster fragments that have been excavated and preserved.

Various artifacts were abandoned when they left, including canteens, bullets, gun parts, and writing tools. But this blog isn’t about buttons, bullets, and buckles. It’s about the items the soldiers found more dear. Objects they made or relied on for small comforts.

So, on a more personal level, what was everyday life like for the Union soldiers stationed here during the Civil War? When they weren’t directly experiencing the brutal and intense combat fighting on the front, it was a routine-filled life of constant drilling, standing watches, maintaining equipment, and finding imaginative ways to entertain themselves in the camps. But camp life had its own struggles and hardships. Poor shelter, food, and hygiene, along with low immunity rates to communicable diseases, all contributed to high rates of sickness and disease. Add to that boredom and homesickness, and camp life was a private’s first test of survival.

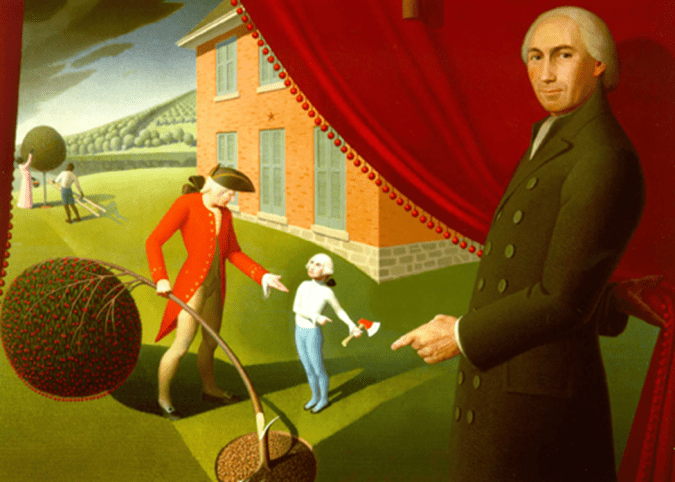

It was very important for the soldiers to recognize that they were standing on the very ground that their hero, George Washington, once stood on. Those sentiments were expressed in a speech by Private Edwin Jones of the 6th Wisconsin when he said, “We are assembled on sacred soil…It was while living on this plantation, under the direction and blessed with the teaching of a noble mother, that George Washington learned those lessons…fitting him for leadership in war and peace, to lay the foundation of the mighty Nation that we today are fighting to preserve.”

On a more personal note, we know soldiers spent a lot of idle time playing games among themselves. Dice, card games, chess, checkers, and gambling were all very popular, and remnants of these activities are found on all Civil War sites. At Ferry Farm, we have a collection of gaming pieces, including this bone die and a gaming piece crafted from a Minié ball, which could have been used to play chess, checkers, or as markers in a game of chance.

And we can’t forget about the importance of music in camp life. Music was a common and welcome pastime activity for troops. Fiddles, guitars, fifes, harmonicas, and accordions all came out at night to entertain the soldiers who relished listening to songs about home and the worries of war. Jaw harps were inexpensive and easily portable, which made them very popular with soldiers. Our jaw harps, one of which was recovered from the civil war trench, is of the style known as a Gloucester type, one of the most common designs in America during Colonial times and after the Revolution.

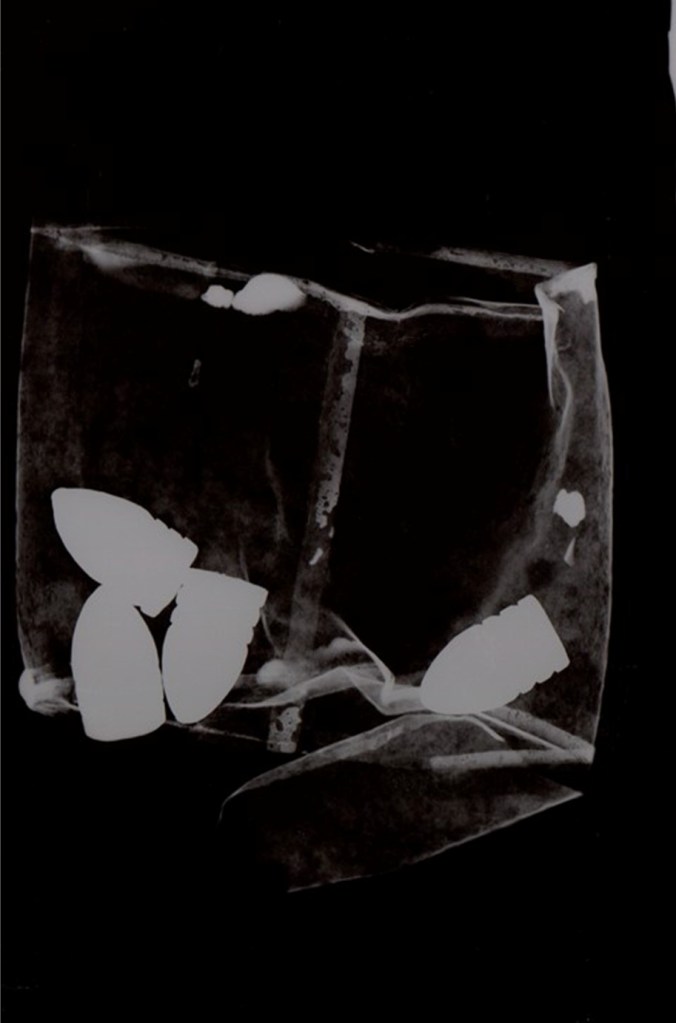

Nothing is normal about wartime. Many people were forced to improvise, and it’s very hard to determine why a soldier placed four unfired Minié balls in this tin can, which was revealed through X-ray. Did he lose his ammo case? Was it just idle behavior? Were these bullets saved to be turned into gaming pieces? This is the type of artifact that raises more questions than answers.

Literacy – Ink Bottle/Pen nib:

Literacy among Civil War soldiers was very high, and much of what we know about daily camp life comes from the letters written and received by the soldiers themselves. Letter-writing to loved ones at home allowed the soldier to keep up with local news, forward monetary and business instructions to those left running the household or farm, and relay war news to their family.

A complete ink bottle and pen nib recovered from the site evidences the desire for correspondence, both official and personal. The ink bottle itself was found in the Bray cellar hole, which the Union soldiers used as a defensive dugout to avoid Confederate sharp shooters. We can just picture a group of soldiers huddled down inside the cellar, building a small campfire to stay warm, and writing letters home to their families. Was it a hasty departure that left this bottle in the cellar, or perhaps the owner expected to return but didn’t. As archaeologists, we can’t answer all these questions, but we know it was used during the Civil War by a Union soldier and was found in a location many soldiers never wanted to be stuck in.

This particular ink bottle is an ‘umbrella’ shape, one of the most ubiquitous ink bottle forms from this era. The bottle was typically meant for single use and would have been made in one of the numerous American glasshouses present during the 19th century. It was then filled with ink, affixed with a label, and marketed for single use.

This small pen nib is stamped with a maker’s mark and style name. The Esterbrook Company started making nibs, including the “Relief” style, in 1858 in Camden, New Jersey, and became one of the largest manufacturers of this product in the US. The nib was part of a dip pen, which consisted of a handle made of various materials and the replaceable nib.

The first evidence of self-care in the trenches takes the form of a small double-sided bone comb. Combs were made from an assortment of materials, including bone, ivory, gutta perch, and steel, and were used for grooming the moustache and hair. But their fine teeth were also handy in capturing the pesky lice that were endemic to camp life among men marching and living together in close quarters. This comb would have been an essential component of any soldier’s personal kit.

Our second evidence of self-care is this intriguing bottle. It is not so much interesting because of what it is – it’s a very common medicine style bottle for the mid-19th century– but rather what’s inside. Clearly visible within the bottle is a hard black substance, and for years, we’ve wondered what the substance may be.

So we chipped off a little fragment of the substance and sent it to Ruth Ann Armitage, our chemist friend at Eastern Michigan University. The sample was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy to map out specifically what elements were present in the sample. Our sample was also run through DART (direct in real time) mass spectrometry. This technique is good at detecting organic components within a substance.

Almost immediately, Dr Armitage responded, and we weren’t disappointed: “Did you know there’s mercury in this?” Nope, we did not.

However, this discovery was not too surprising given the use of mercury in many medicines for thousands of years. Nowadays, it’s common knowledge that you shouldn’t drink mercury…or touch it…or inhale it, but for a long time, mercury was seen as a potent healing metal, and it was readily rubbed on skin, consumed, and vaporized for immediate effect on the lungs.

And while all these treatments using mercury did little to address the body’s underlying medical problem, mercury did cause an immediate bodily response, which convinced people it was working to cure their ailments. When applied topically, it burned. When introduced into the body, it caused a person to sweat, salivate, and have diarrhea. The mucous membranes also went into overdrive, leading many to believe that the bad stuff in your system making you sick was being purged by the mercury. The reality, of course, was that the body was trying desperately to rid itself of poison.

So, if the residue inside our bottle was medicine, what was its exact formula? All we can say at this point is that it was mercury-based and that it could have been in either liquid or pill form. Common Civil War-era uses for mercury-based medicines were for treating skin sores and lacerations, internal and external parasite infections, syphilis, and constipation, to name but a few. On a side note, an almost identical bottle also containing mercury was found across the river in Fredericksburg at a site that was well known to be a Union field hospital. It was found in a knapsack discarded in a trench that included amputated limbs.

Lastly, we’d like to highlight one of our favorite artifacts, a tiny hatchet about two and a half inches long, recovered from the bottom of the Civil War trench. For such a diminutive object, it speaks quite loudly to our local history in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Initially, earlier archaeologists at Ferry Farm assumed it was a pewter toy souvenir given out or sold in 1932, when our country and Fredericksburg celebrated the 200th anniversary of George’s birth. Indeed, cheap pewter toys were very popular during this time period.

A recent reexamination of all the artifacts from the context where the hatchet was found revealed that nothing from that stratum had any 20th-century artifacts in it, nor did the two strata above it. In fact, the youngest artifacts from these strata were all mid-19th century. Additionally, although the archaeologists who excavated the hatchet didn’t know it at the time, the excavation unit from which the hatchet came sat right inside the Civil War-era trench.

This revelation shut the door on our ‘it’s a 20th-century souvenir’ narrative but opened the door to an even cooler one. A close examination of the hatchet showed that it didn’t have mold seams, which are always present on cast pewter toys. Furthermore, for some reason, it had one smooth side and one textured side, leading us to believe that it was handmade, not machine-cast. This was supported by a thorough internet search to find an identical toy hatchet, which came up empty, further supporting our new theory that this piece was a one of a kind. The textured side resembled the grain of wood, so we surmised it had been cast in a simple hand-carved wooden mold. All of these clues, combined with its location within a Civil War trench, made us suspect that the hatchet was crafted by a soldier, likely from a lead Minié ball. The hatchet is likely ‘trench art’, which is defined as objects of art either made by soldiers, POWs, or by civilians to create mementos of the war experience.

To further support our identification of the hatchet as trench art, we took the artifact to the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, where Katherine Ridgeway analyzed it using XRF, or X-ray fluorescence analysis. This non-destructive technique determines the composition of metal. We also brought along a few Minié balls recovered from the same unit for comparison. It turned out that what we thought was a pewter hatchet was actually a lead hatchet with a similar compositional profile to Minié balls, which are mostly lead with trace amounts of other metals such as tin and nickel.

One can just imagine a bored Union soldier whittling the mold and then melting down some of his bullets to pour into it. He likely chose the hatchet form because of the famous cherry tree story, in which young George Washington owned up to hacking his father’s cherry tree with a hatchet by proclaiming, ‘I cannot tell a lie.’ The soldier would have been well-versed in the Washington cherry tree myth at Ferry Farm, created by Mason Locke Weems in his first biography of Washington, published in 1800. By the 1860s, the story was nationally known. Additionally, letters Union soldiers wrote while encamped at Ferry Farm indicate they knew the site’s connection to Washington. They even went so far as to send home cherry seeds for their families.

While the identification of the hatchet is now secured, we have so many more questions. Who was this soldier? How many hatchets did he make, and why did this one come to be left behind in his trench? Was it a souvenir for himself, or did he send one home to his family, or share with fellow soldiers? Did he survive the war? Unfortunately, these are mysteries that will likely never be solved, but that make for great pondering.

Mara Kaktins, Archaeologist and Lab Manager

Judy Jobrack, Archaeology Co-Field Director