Welcome back to our 3-Part Blog charting tuberculosis in the extended Washington Family. If you are new to this series, Part I examined how the disease works, charted its history, and explained standard courses of treatments in the 1700s. You can find the blog here, and we encourage a review of the “Treatment” section. In Part II, we will begin to look at the family members who suffered from the disease and how this impacted their lives and those around them.

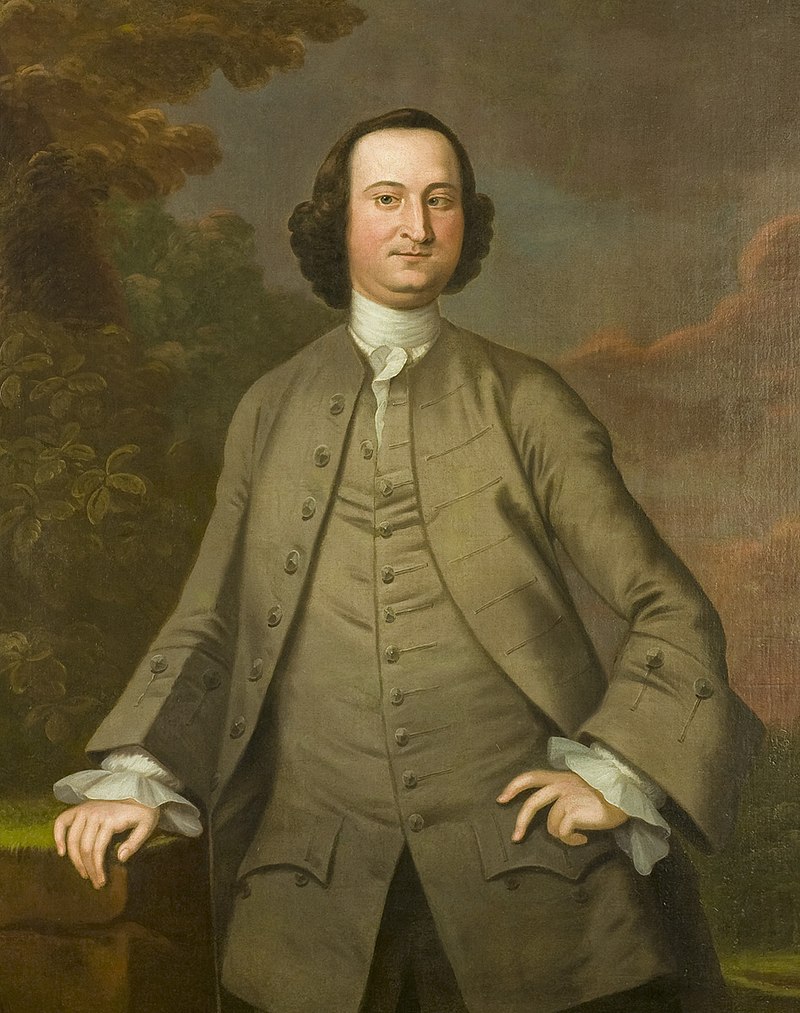

Lawrence Washington (1718-1752, aged 33/34):

Perhaps the best-known case of tuberculosis in the Washington family pertains to Lawrence Washington. George’s eldest half-brother, credited as serving as a role model, died of the disease in 1752, which subsequently laid the foundations for George to inherit Mount Vernon and become the Father of His Country. Behind this, however, lies one of the more clear timelines for the devastation the disease.

Lawrence may have contracted tuberculosis during his service in the War of Jenkins’ Ear (served 1740-1742) or after his return to Virginia in 1742. Certainly, he had developed severe enough symptoms, particularly a cough, by the end of 1748, to cause him to take a leave of absence from the House of Burgesses. He resumed his duties in the spring of 1749, but his illness forced him home for a final time in May. That same month, George wrote hoping for news that his brother’s cough had improved and that he had “given over the thoughts of leaving Virginia.”1 Lawrence could not provide his brother with the news he desired, and sailed to England in the summer of that year to consult with physicians. Lawrence returned in November with little encouragement, but set out for Berkeley Springs in July 1750, to take the waters. George accompanied his brother on this venture, but they did not stay long.

By 1751, Lawrence had exhausted any hope of finding a cure at home and his doctors recommended visiting a warmer climate. Following this advice, Lawrence and George sailed for Barbados on 25 September and arrived on 2 November. Shortly after their arrival, George recorded that a doctor came “to pass his opinion on [his] brother’s disorder, which he did in a favorable light, giving great assurances that…a cure might be effectually made.”2 George mentions little else of Lawrence’s condition in his journal, a month of course went undocumented as George had smallpox, and he returned to Virginia alone in December.

Lawrence, having not found the relief he hoped for, decided to try Bermuda and journeyed there after George left. In an April 1752, letter to a friend, Lawrence referred to Bermuda as his “last refuge, where [he] must receive [his] final sentence.”3 Describing himself as “a criminal condemned, though not without hopes of a reprieve,”4 Lawrence followed his doctor’s treatment plan by “abstaining from flesh of every sort, all strong liquors, and by riding as much [he] could bear.”5 His doctor advised to take what benefit he could from the climate as another winter in Virginia would surely kill him. While Lawrence remained somewhat hopeful in this letter, he soon wrote again about his “unhappy state of health”6 and expressed the belief that, if it should worsen, he would “hurry home to [his] grave.”7 Evidently, Lawrence soon resigned himself to his impending death as he returned to Mount Vernon and set his affairs in order with the aid of his half-siblings and stepmother. He died on 26 July 1752.

Upon Lawrence’s death, he left behind his wife Anne Fairfax and daughter Sarah. Three other children had already died all under the age of two. Infant mortality frequently occurred in the 1700s, so it proves impossible to know what caused each death. However, it remains a possibility that they contracted tuberculosis from their father, which then killed them quicker due to their age and weaker immune systems, or left them vulnerable to secondary infections. Sarah would suffer a similar fate in 1754, aged four, and her mother, having married into the Lee family, would die in 1761, aged thirty-three. These deaths allowed George to inherit Mount Vernon.

Fielding Lewis (1725-1781, aged 56):

The husband of Betty Washington and the mind behind Kenmore, Fielding Lewis served his country during the war by funding various supply and defense lines. One of the richest men in Virginia, Fielding had the ability to provide aid and, as the brother-in-law of the commander-in-chief, could hardly stay out of the conflict. While his efforts did much for the cause, Fielding drew the short straw by spending nearly all of his money. Accounts of Fielding Lewis’ death often insinuate a connection to the stress of losing his fortune. While this certainly put him under strain, and would not have helped his health, Fielding’s case of tuberculosis meant that he would have died regardless of his financial status.

Tracing tuberculosis in Fielding’s life proves more difficult than that of Lawrence. Mentions of Fielding as ailing exist for several years prior to his death. However, with no description, one can hardly say if this references tuberculosis or some other affliction. Like many, he frequented Berkeley Springs and even purchased property there. Fielding recorded little of his visits, but his interests lay in the spring’s supposed medicinal benefits and, to that end, undertook an annual August trip from 1772 onwards. Throughout the war, Fielding held the rank of colonel and, though he never received a formal posting, oversaw Fredericksburg’s gun manufactory and the defense of the Rappahannock. This position required no military action and had strong connections to his background as a merchant. However, the choice of assignment may have derived from knowledge that he would never be well enough to effectively command troops. Then again, Fielding was in his fifties and had no military experience. In any case, the position reflected a strategic choice that played to Fielding’s strengths and lessened the impact of field inexperience and ill health.

If Fielding hoped for a peaceful death, he would not receive it. In the summer of 1781, with the British encroaching on Fredericksburg, the Lewis household and Mary Washington fled. At this stage, Fielding’s health had significantly deteriorated, leaving him an invalid confined to his home. A sudden evacuation by carriage would have done little to ease his discomfort as the household hurried to another property in Frederick County, Virginia. Once there, Fielding focused on putting his affairs in order and likely did not have the strength to visit nearby Berkeley Springs. The news of the Yorktown victory undoubtedly brought some emotional respite, but it proved short-lived as Fielding died mid-December 1781. The location of his burial site on the Frederick County property remains unknown. Fielding’s death brought immense grief to his widow, Betty Washington, who had lost her brother Samuel to the same disease only three months earlier.

Samuel Washington (1734-1781, aged 46):

The second son of Augustine Washington and Mary Ball, Samuel grew up at Ferry Farm with his full-siblings. Said to have suffered from tuberculosis for most of his life, it remains unknown where, when, and from whom he contracted it. However, by visiting Lawrence in July 1752, to help put his half-brother’s affairs in order, seventeen-year-old Samuel certainly faced exposure. Samuel died at his home Harewood, near Charles Town, West Virginia, in September 1781, shortly before the victory at Yorktown. The home itself lies conveniently close to Berkeley Springs, which may indicate that its location and Samuel’s move from Stafford County, Virginia, derived from a desire for easy access to the springs and their reputed health benefits.

Despite dying just shy of age forty-seven, Samuel famously married five times. His final wife, Susannah Perrin Holden (1753–1783, m. 1778), survived him, and the fourth, Anne Steptoe (1737–1777, m. 1764), died of complications from a smallpox inoculation. However, the deaths of his first three wives, Jane Champe (1724–1755, m. 1754), Mildred Thornton (roughly 1741–1762, m. 1756), and Lucy Chapman (1743–1763, m. 1762), have long been associated with tuberculosis.

All three experienced rapid declines in health after their marriages to Samuel, and in correlation with several pregnancies. Pregnancy and childbirth proved extremely dangerous during this period, so these deaths could simply be tragic examples. However, as pregnancy exacerbates tuberculosis, the common interpretation remains that the women contracted the disease from Samuel, saw it worsen at an alarming rate due to pregnancy, and the strain of one or more births on top of the disease made it impossible to recover. Regarding his children, several died quite young, which may mirror the fate of Lawrence’s children, and three of his sons who reached adulthood would ultimately die of the disease.

Coming Up

In our final blog on tuberculosis, we will be taking a look at how the disease impacted the next generation of the extended Washington family and those they enslaved. This will be coming out on June 28th.

Emma Schlauder

Research Archaeologist

Bibliography

2-7 Anderson, Alicia K. & Lynn A. Price (editors) 2018 George Washington’s Barbados Diary: 1751-52. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, VA.

1 Chernow, Ron 2010 Washington: A Life. Penguin Books Ltd, London, UK.

Felder, Paula S. 1998 Fielding Lewis and the Washington Family: A Chronicle of 18th Century Fredericksburg. The American History Company.

Glen, Justin 2014 The Washingtons: A Family History, Vol 1, Seven Generations of the Presidential Branch. Savas Beatie LLC, El Dorado Hills, CA.