If you have visited Ferry Farm recently or follow us on social media, you may have noticed the construction of two buildings near the Washington House. These new structures represent ones that stood in these spots during George Washington’s time. Identified through archaeology, their reconstructions allow us to better tell the stories of the people who lived and worked at Ferry Farm. For this blog, we will look at the structure adjacent to the Washington House along the embankment overlooking the Rappahannock: The Quarter.

What’s in a Name?

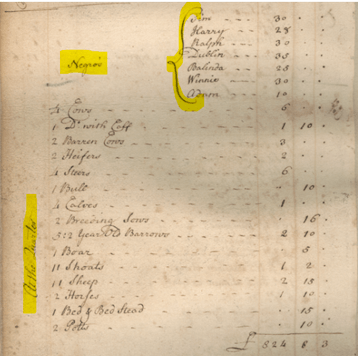

First, we need to define what we mean when we call the structure “the Quarter.” Regarding enslaved life, the term “quarter” can refer to several different situations. Generally, it refers to a structure that housed enslaved individuals with “quarter,” equating to a living space or personal quarters. The term has nothing to do with the number and makeup of the occupants or the appearance of the building. The other use for the term refers to a group of enslaved people. Augustine Washington’s probate inventory lists seven enslaved people at Ferry Farm’s “satellite quarter” (Fig. 1). In this use, it does not refer to a single physical structure but rather a group of people and their housing unit that moved around. “The Quarter” uses the term for a single structure, identified through archaeology, that housed an enslaved family in the heart of the Ferry Farm plantation.

Enslaved Housing

Living conditions varied widely across the Mid-Atlantic and even within a single plantation. Customarily, enslaved people lived where they worked. Work yard structures included living quarters above the workspace while the fields had structures akin to dormitories that housed people divided by biological sex. In certain cases, independent structures may have served as housing for single family units (Fig. 2). Those that lived within these spaces generally held high ranking positions within the hierarchy established by enslavers. Housing generally stood outside public view and in areas convenient to the work undertaken by the inhabitants. Quarters within sight of the public served as status symbols for the gentry.

Identifying quarters today largely comes from historic records, oral history, archaeology, and architectural features. All of this can help establish a range of appearances for such structures. When a building no longer remains standing, these observations can be compared to artifacts uncovered at the site to determine its identity. Sub-floor storage pits, often located near hearths, serve as key architectural identifiers, while artifacts that reflect African diaspora culture, outdated items, and evidence of labor help pinpoint the identities of the inhabitants. Quarters served as the only personal spaces allotted to enslaved people, so any artifacts recovered can speak to their personal identities rather than those defined by Virginia colonials.

Archaeological Evidence

The excavation of the Quarter occurred in 2003, and research in successive years helped to identify its role and understand the lives of its inhabitants.

- Architecture: When excavated, little remained of the Quarter, but the architectural elements present and absent provided enough information to understand its appearance. Archaeologists recovered small quantities of Aquia sandstone around the quarter indicating it may have had a light stone foundation and hearth. The main impact it had on the ground surface occurred through the creation of a sub-floor pit. These pits frequently appeared in quarters and served as storage areas for the occupants’ personal effects. Unfortunately, a tree later intruded a portion of the pit and the surrounding area thus making it difficult to study (Fig. 3). Other architectural elements included an abundance of nails and an absence of window glass (Fig. 4). This indicates the building had clapboard siding and likely shuttered windows in place of glass ones.

- Tableware (Fig. 5): Within the eighteenth-century contexts, we recovered many ceramics and utensils of European origin. White-salt glazed stoneware dishes and dog-nosed spoons represent styles in decline by the 1740s. This indicates that the enslaved occupants either received hand-me-downs from the Washingtons, a common practice, or purchased used items in the local market. A colonoware bowl served as an exception. A local ceramic type attributed to free and enslaved black communities, colonoware production mixed African ceramic techniques with European vessel forms.

- Small Finds (Fig. 6): Analysis of the artifacts revealed the personal effects of the occupants, their possible identities, and the labor they carried out. Wig curlers appear frequently throughout Ferry Farm, but the recovery of several at the Quarter indicates that the individual(s) tasked with maintaining the Washington wigs may have lived within. Sewing implements, such as thimbles, reflect labor carried out by enslaved women and girls either for the Washingtons or for themselves. A common practice in colonial Virginia saw each enslaved person receive a ration of cloth from which they fashioned their own clothing. Straight pins further indicate the presence of female occupants as these pins held their garments, such as bed gowns, together. Both genders used the numerous tobacco pipes recovered. The fishhook speaks to an entirely personal activity, as enslaved communities often supplemented their food rations by fishing. The pierced coin serves as the artifact most indicative of enslaved culture. Piercing a coin allowed the owner to keep it on their person as a form of adornment. Such coins often served as talismans, though they could re-enter the economic world as needed.

- Diet (Fig. 7): Faunal remains found at the Quarter supplement the information provided by the fishhook. As expected, we identified several fish species including types of perch, catfish, and sunfish which lived in the Rappahannock at that time. Other animals included cattle, chickens, pigs, opossum, and shellfish, such as oysters. This mix of domestic and wild species indicates that the Quarter’s occupants supplemented the rations supplied by the Washingtons. The enslaved commonly achieved this by maintaining small gardens and raising chickens, hunting, fishing, and foraging. While we did not recover any plant remains, those consumed by the inhabitants likely reflected a similar mix of wild and domestic species.

Reconstruction and Interpretation

The reconstruction of the Quarter combined our archaeological evidence with the historic knowledge of enslaved housing (Fig. 8). The finished Quarter measures 16’x14’ which aligns with standard measurements for single-family quarters. From our archaeology, it has clapboard siding, sliding shutters in place of glass windows, a subfloor pit, and sandstone hearth. Information on contemporary quarters led to the inclusion of a loft and a daub lined wood chimney. Architects used eighteenth-century techniques to reconstruct the building.

From our findings, we concluded that the quarter housed a single family. At least one of these individuals held a high-ranking position within the labor hierarchy allotted these living arrangements (Fig. 9). The structure’s proximity to the Washington House and work yard indicates the occupants worked within these spaces. The position on the bluff overlooking the Rappahannock meant that this quarter, unlike others, lay in view of the public. “The prominent placement of this structure on the landscape may mean that it was used to reinforce Washington’s prominent social standing in colonial Virginia.”

The Quarter will open to visitors this fall, and visitors will be able to read about and visualize the lives of those who lived within. Like the Washington House, everything that furnishes the Quarter will be interactive and reflect archaeological finds. Planning remains ongoing for this, but when complete, visitors may find outdated tableware, evidence of meals, tools for labor, and personal effects.

Emma Schlauder

Research Archaeologist

Bibliography

Augustine Washington Probate Inventory, 1743

Carson, Cary & Carl Lounsbury (editors) 2013 The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

Katz-Hyman, Martha B. & Kym S. Rice (editors) 2011 World of a Slave: Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the United States. Greenwood, Santa Barbara, CA.

Lanier, Gabrielle M. & Bernard L. Vlach 1997 Everyday Architecture of the Mid-Atlantic: Looking at Buildings and Landscapes. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Lounsbury, Carl R. (editor) 1994 An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Samford, Patricia 1996 The Archaeology of African-American Slavery and Material Culture. William & Mary Quarterly 53(1): 87-114.

2000 Power Runs in Many Channels: Subfloor Pits and West African-Based Spiritual Traditions in Colonial Virginia. Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Stilgoe, John R. 1982 Common Landscapes of America, 1580-1845. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Wells, Camille 1993 The Planter’s Prospect: Houses, Outbuildings, and Rural Landscapes in Eighteenth Century Virginia. Winterthur Portfolio 28(1): 1-31.

Vlach, John M. 1993 Back of the Big House: the Architecture of Plantation Slavery. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.