Some of the most delicate objects in our collection are our archives. Paper and other document materials like vellum and parchment are very sensitive materials that can be irreversibly damaged simply by light. This makes it very difficult to display or put on exhibit for extended periods despite our comprehensive policies for conserving and preserving documents; exhibition has always been unfeasible. To remedy this, we have been working on getting archival-safe, high-quality images of our important documents online for everyone to access. So, while you might not see the documents in person, you can still explore, read, and learn about these important papers while we preserve them for future generations.

Until we launch our online archives, I wanted to give everyone a sneak peek at a few of our incredible pieces.

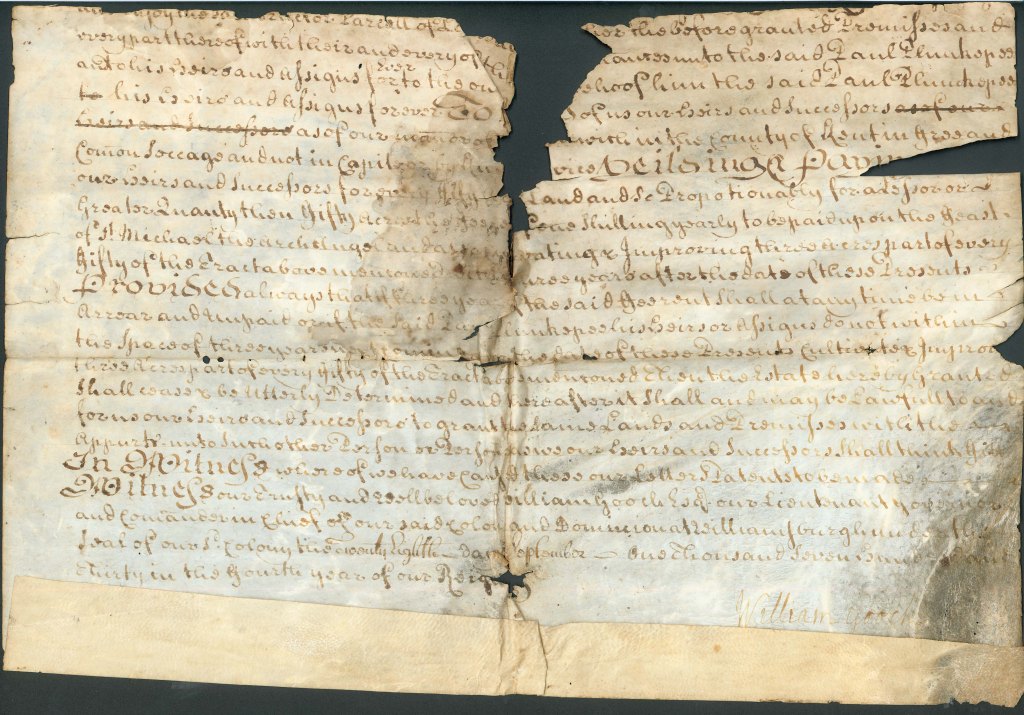

One of our oldest documents in the collection is a Land Grant signed by William Gooch on September 28, 1730, written on vellum. William Gooch was a colonial administrator who served as governor of Virginia from 1727 to 1749. The grant is not in the best condition, but it reads that it grants 400 acres in Spotsylvania County to Paul Plunkepee. This grant is officially recorded as Land Office Patents, No. 14, 1728-1732, page 40, and is available at the Library of Virginia.

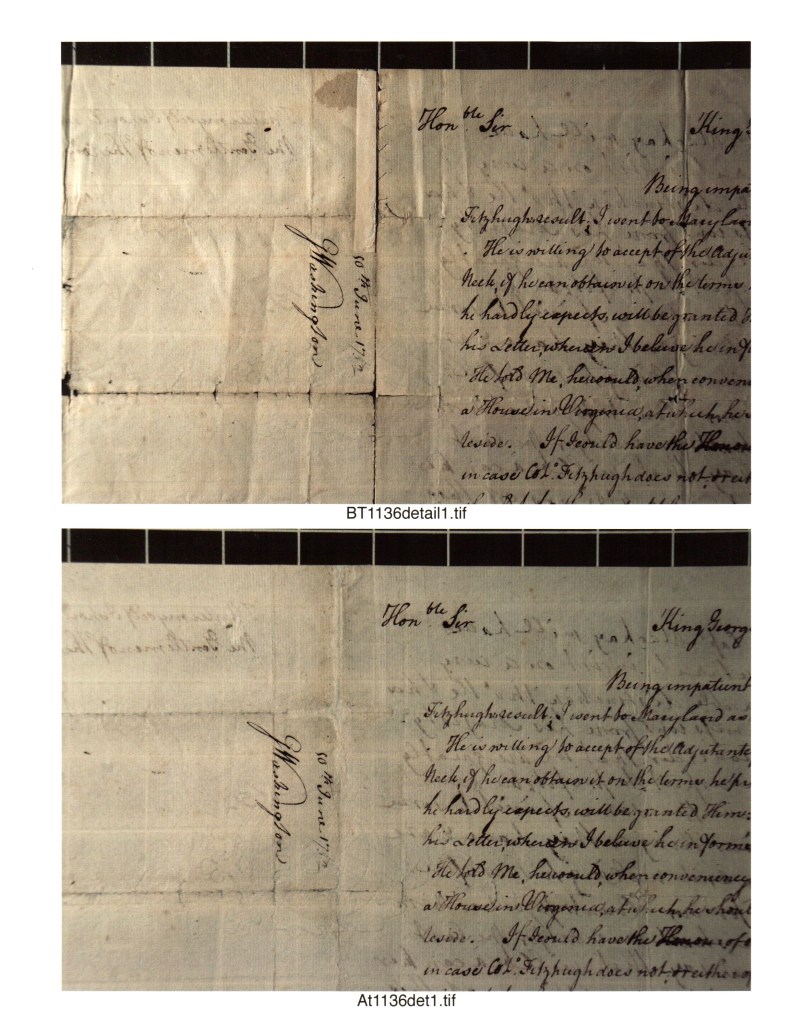

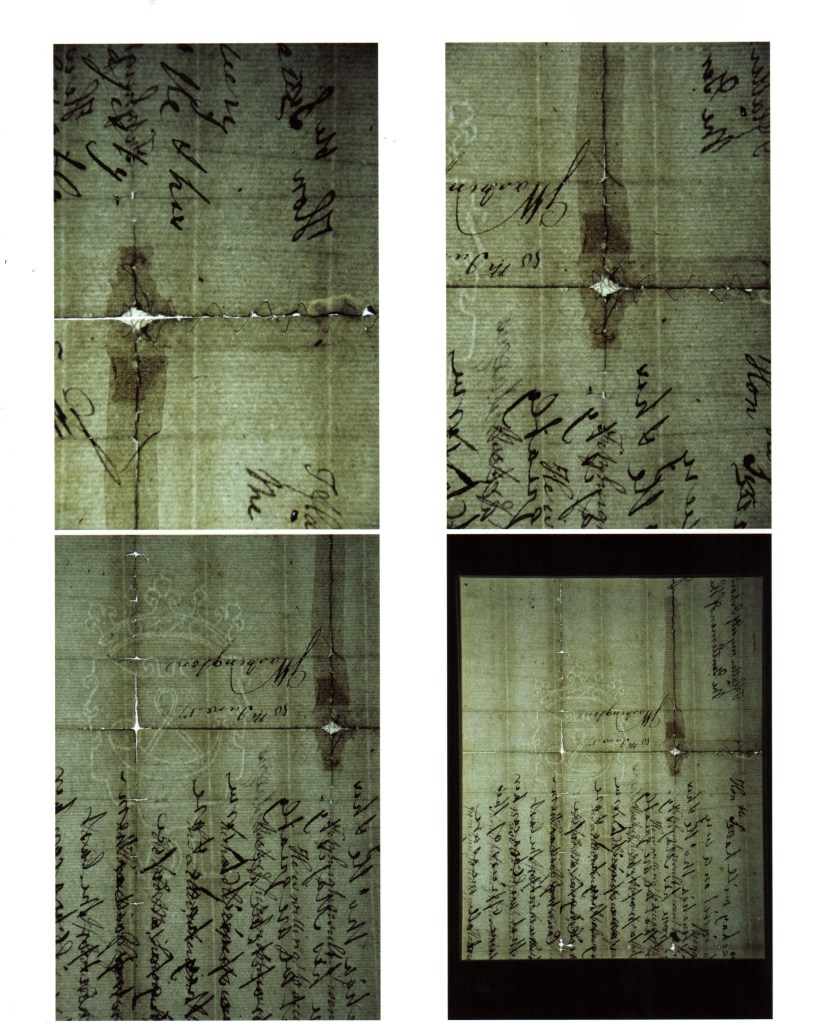

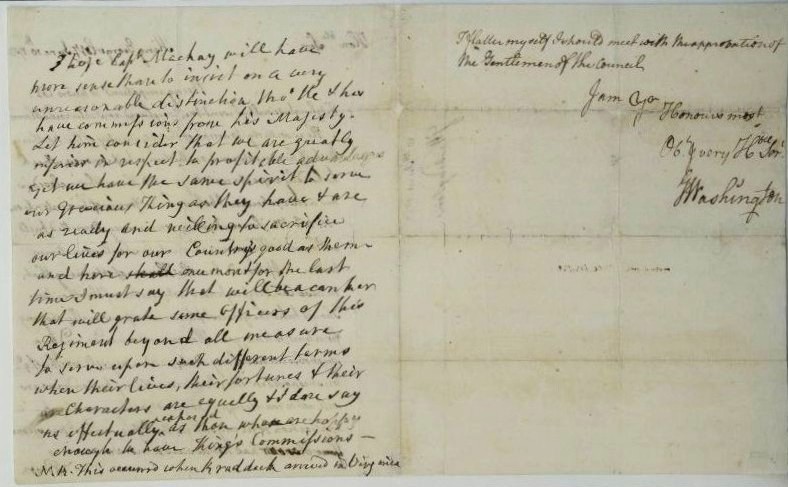

One of our most unique documents is a letter from George Washington to Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie, written on June 10, 1752, when he was twenty. Robert Dinwiddie served as Lieutenant Governor of Virginia from 1751 to 1758. In the letter, George requests his first military appointment to the open adjutancy of the Northern Neck or other district. George’s half-brother Lawrence had been appointed Adjutant General of the colony in 1743. Due to his illness and eventual death, the adjutant was to be divided into smaller districts (i.e., Northern Neck).

Dinwiddie declined the appointment but assigned George to an envoy position that winter to confront the French, who had recently built a fort on what Dinwiddie considered British land. Additionally, George met with the Iroquois Confederacy to make peace and obtain intelligence about the French.

This amazing letter pinpoints the beginning of George Washington’s illustrious military career, which would eventually culminate in him becoming the first President of the new United States of America. The letter is in great condition after meticulous conservation work, which included repairs with Japanese tissue called tengucho and wheat starch paste called jin shofu. It was then cleaned and flattened, and the iron gall ink stabilized.

A transcript of the letter can be found on the National Archives website at Founders Online.

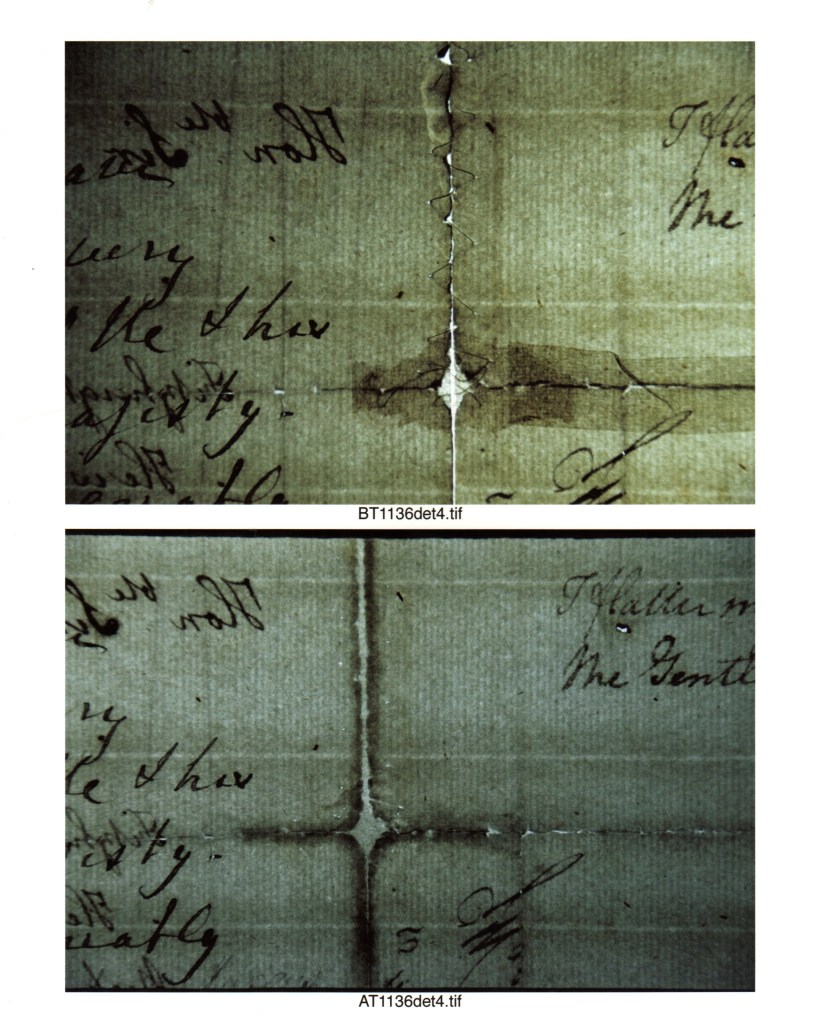

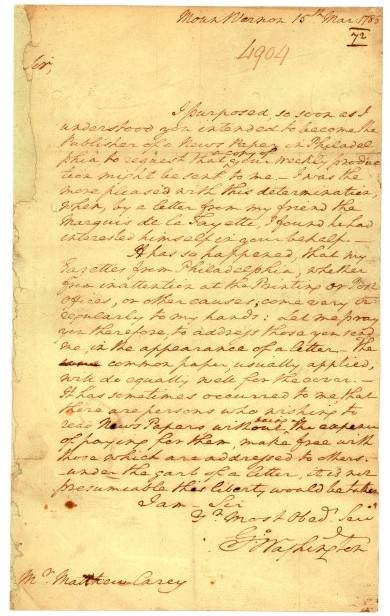

Next are two letters between George Washington and Irish-born publisher Matthew Carey. Matthew Carey moved to America in 1784 and settled in Philadelphia, where he established a publishing business and bookshop with $400 given to him by the Marquis de Lafayette. Carey’s first publication was The Pennsylvania Herald in 1785, followed by two of the first successful American magazines, The Columbian Magazine and The American Magazine in 1786 and 1787.

In George’s first letter to Carey in 1785, he requests a subscription to Carey’s newspaper but asks him to send the newspaper disguised as an ordinary letter because George has been having problems with the post office delivering his newspapers . George thinks his papers may not have been delivered because “persons who wishing to read News Papers without being of the expence [sic] of paying for them, make free with those which are addressed to others.”

The second letter between George and Matthew is dated June 25, 1788. The year before, Carey launched “The American Museum” magazine. It was a literary museum that reprinted significant historical documents on American history and original essays on politics, commerce, and culture. The magazine got a positive response, but Carey was finding it expensive to distribute the magazine across the country, so he asked George, one of his first subscribers, to write an endorsement for the magazine that would help attract new subscribers.[2]

Washington responded immediately, seizing the opportunity offered by Carey to express his belief that the free dissemination of information and ideas was vital to preserving American liberty. ‘I could heartily desire,’ Washington wrote, that ‘copies of the Museum and Magazines, as well as common Gazettes, might be spread through every city, town & village in America – I consider such easy vehicles of knowledge, more happily calculated that any other, to preserve the liberty, stimulate the industry and meliorate the morals of an enlightened and free People.”

Carey published Washington’s endorsement in the next issue of his magazine—his marks for the typesetter can be seen in the original Washington letter. The result was a flood of new subscriptions that allowed Carey to continue publishing The American Museum for another four years.

Transcripts of the letters can be found on the National Archives website at Founders Online.

These are just a few of the amazing documents in our collection, which we hope to bring you soon so that you can explore them yourself. Check back often, and we will keep you updated on our progress with our digitization project.

Heather Baldus

Collections Manager

Bibliography

Edd Applegate (August 17, 2012). The rise of Advertising in the United States: A History of Innovation to 1960. Scarecrow Press. p.25.