There once stood a large horse chestnut tree on the corner of Fauquier and Charles Street in Fredericksburg. It was noted as one of the thirteen legendary Washington horse chestnut trees planted by George himself. By the 1930s, it was becoming clear that the tree needed some help, so the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) took up the cause to protect this historic tree.

The tree legend states that George, while visiting his mother in June 1788 in Fredericksburg, decided to plant thirteen horse chestnut trees from her house to his sister’s house, Kenmore, just a few blocks away. This provided a scenic path for his mother when she visited her daughter Betty. These trees commemorated the thirteen original states.

It is a great story. It is patriotic and nostalgic, showing George as a man of the earth with his love of trees, gardening, and horticulture. He planted these trees for a future America to remember the struggles to create this country and the precious nature of our land that we must protect.

But is it true? Did George plant that tree? What is the evidence?

The horse chestnut tree is a native of the Balkans region (Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, and Northern Macedonia). It made its way to Europe and England during the seventeenth century, noted as growing in South Lambeth, London, and being planted by Sir Christopher Wren at Hampton Court.

There is documented evidence of some horse chestnut trees crossing the Atlantic to Mr. John Bartram, one of America’s first botanists in the 1740s. In a letter from Peter Collinson, an English botanist, dated September 16, 1741, he wrote to Bartram, “I have sent some Horse-Chestnuts which are ripe earlier than usual; hope they will come fit for planting.”. Bartram acknowledged receiving them and stated that most were blue-molded, and only one germinated and grew. Over twenty years later, Bartram updated Callison on the success of the lone seedling, writing, “But what delights me is that our horse chestnut has flowered. I think it must excel in America.”

Bartram’s Gardens in Philadelphia was quite popular and visited by many founding fathers while working there. George visited the gardens twice in the summer of 1787 while in the town during the Constitutional Convention, noting, “Sunday, June 10, 1787, breakfasted at Mr. Powell’s and in company with him rid to see the Botanical Gardens of Mr. Bartram, which, though stored with many curious plants, shrubs, and trees, many of which are exotics, was not laid off with much taste, nor was it large.”

Why mention this? In some versions of the story, Washington got his horse chestnut trees from this garden, but there is no evidence that the legendary trees were obtained from this famous historic garden.

George only made two diary entries about horse chestnut trees on April 13, 1785, writing, “Received from Col. Henry Lee of Westmoreland 12 horse chestnut trees (small) and an equal number of tree boxes. They appeared to have been some time out of the ground. Planted 4 of the Chestnuts on my serpentine walk – two on the east end and the rest in the vineyard.” And again, on April 2, 1788, wrote, “Transplanted from a box in the garden, thirteen plants of the horse chestnut into shrubberies by the garden walls.”

The entry shows evidence of planting the famous Washington trees, right? No, because George was at Mount Vernon in April and didn’t leave for Fredericksburg to visit his mother until June 10, 1788.

But could he have had them sent down and have them planted before he came to see his mother? Yes, but the story says that George planted these trees with his own hand. Additionally, it would be odd for George to mention planting the trees while in residence at Mount Vernon and not say that they were in his mother’s garden in Fredericksburg. Washington was a diligent diarist but never mentioned planting thirteen horse chestnut trees in his mother’s garden.

Further, no known letters from George, Mary, or Betty mention any horse chestnut trees between Mary’s gardens and Betty’s Kenmore.

This was all the primary source evidence I could find relating to George and any horse chestnut trees. So, I looked further into the story to see what other evidence was being used to verify that this tree was indeed one of the thirteen Washington trees.

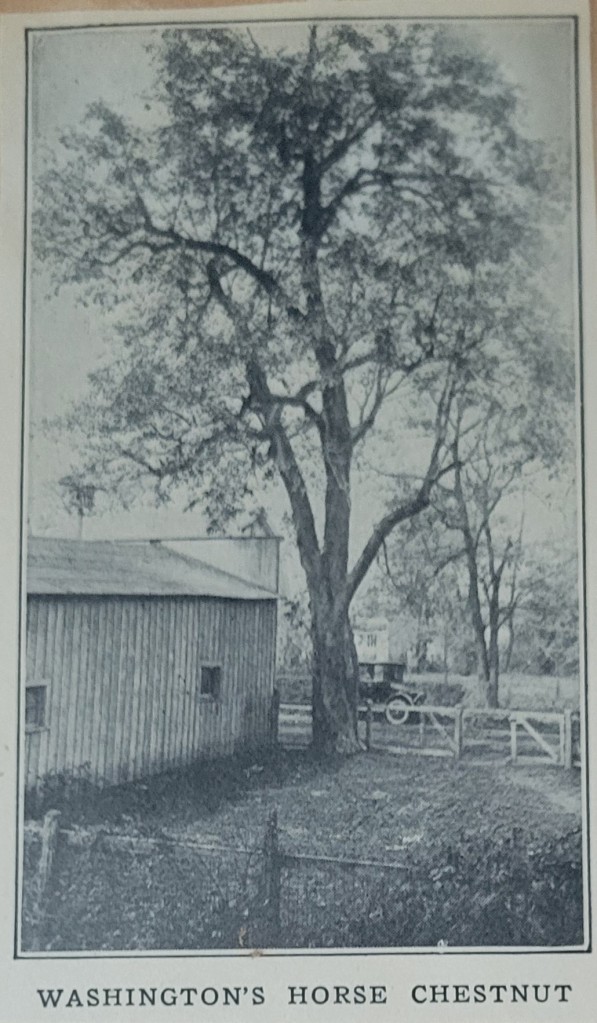

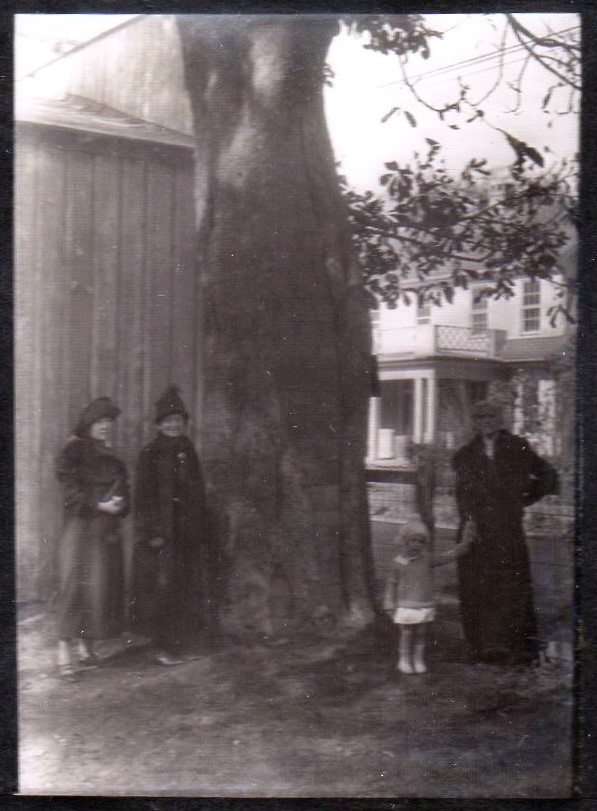

As I said in the beginning, by the 1930s, many, including the DAR, were trying hard to save this lone surviving chestnut tree. With their extensive reach, they got Fred H. Arnold, the Assistant Forester for the National Park Service, to do an age-determination test on the tree in May of 1934. Mr. Arnold noted some issues with the test, stating that the lower twelve feet of the tree was filled with concrete, so the coring sample had to be taken above this “repaired defect”. Even then, a complete coring sample could not be extracted due to decay in the interior of the main stem. Additionally, Mr. Arnold said that it was very difficult to count the annual rings due to their obscurity because the texture difference between the springwood and summerwood for the horse chestnut tree (genus Aesculus) is very slight. Taking into account all this, Mr. Arnold estimated the tree to be around 139 years old with as much as 10% in error, either plus or minus, which would put the date it was planted somewhere between 1781 and 1809, which means that the tree is indeed old and could have been planted during Washington’s time in Fredericksburg.

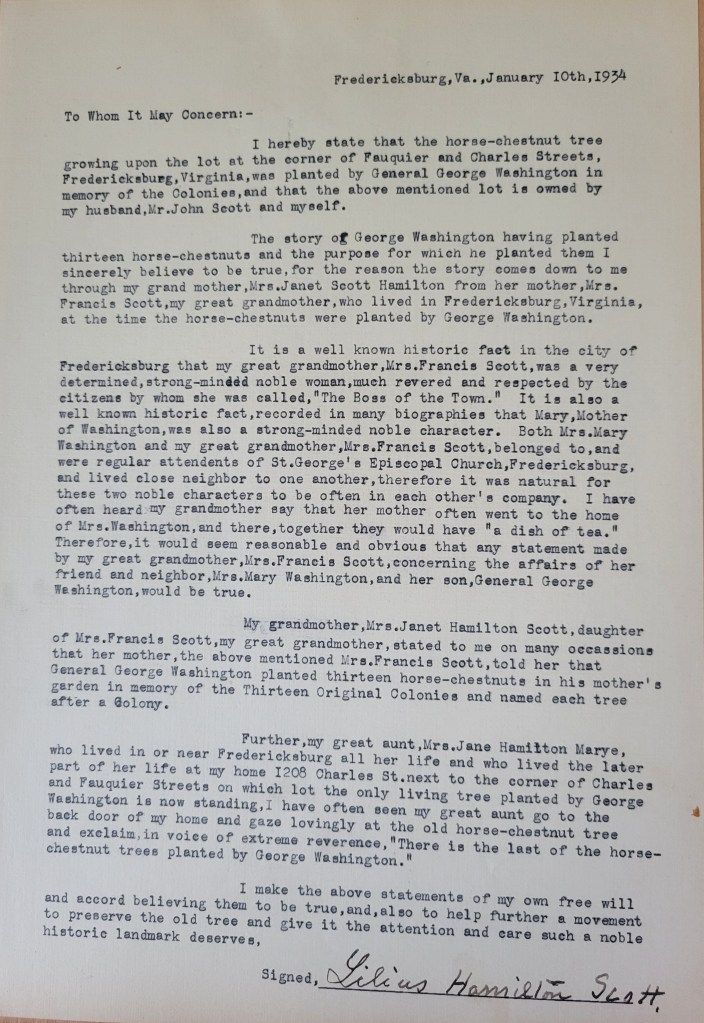

Lastly, local historian James Henry Heron collected local citizens’ recollections of the tree and the story. Mrs. Lilias Hamilton Scott, the wife of Mr. John Scott, who owned the lot on which the tree stands, wrote that her grandmother (Mrs. Janet Scott Hamilton) stated her great-grandmother (Mrs. Francis Scott) resided in Fredericksburg in 1788 and was Mary Washington’s neighbor and intimate friend. She said the trees were planted by Washington.

Mrs. Vivian Minor Fleming traces the story back to Miss Lou Carruthers, her sister Mrs. Davis, and their grandfather Rev. S.B. Wilson’s housekeeper, Mrs. Polly Skelton, who had previously been a housekeeper for Mary.

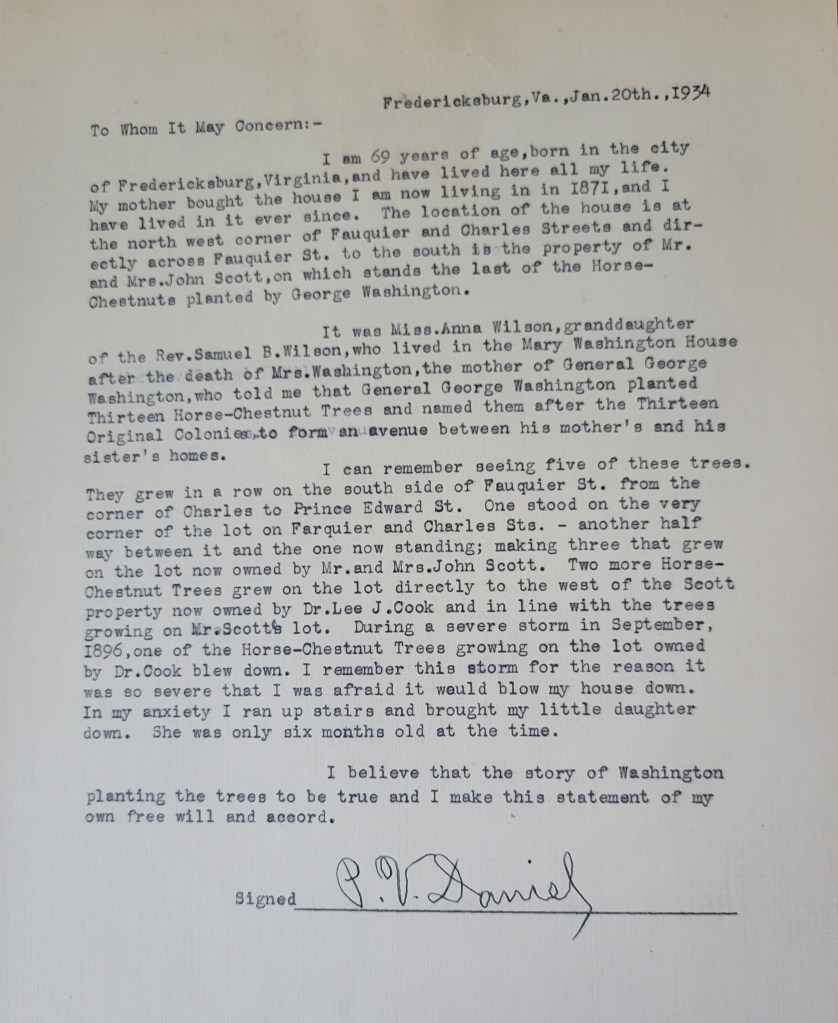

Mr. P.V. Daniel, who remembers five of the original thirteen trees, lived across the street from the remaining one for over sixty years and said Miss Anna Wilson, granddaughter of Rev. S.B. Wilson, told him the story.

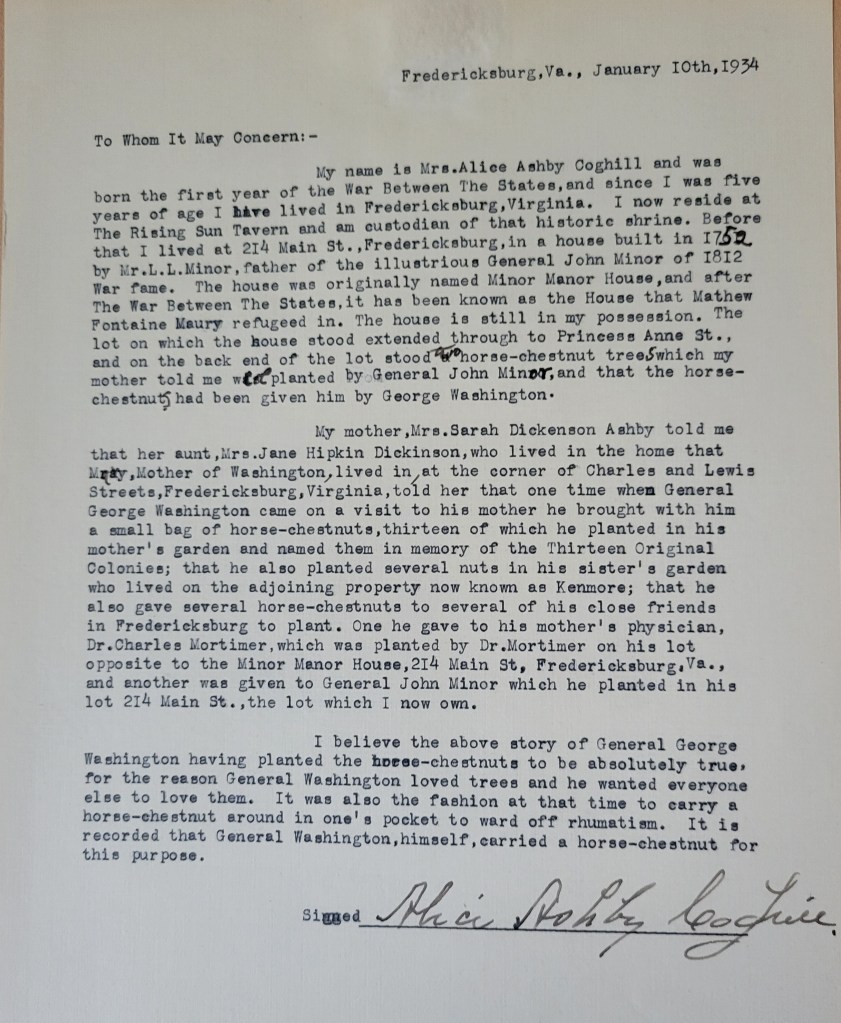

Mrs. Alice Ashby Coghill says her aunt, Mrs. James Hipkin Dickinson, who lived at Mary Washington House after Rev. S.B. Wilson said Washington planted the trees and passed out horse chestnuts to friends.

While I have no doubt these people are truthful in their recollections, they do not offer any definite evidence. They merely document that the legend was a well-known story but not that it was true.

Regardless, the much-loved old tree was rightfully given proper emergency care with a donation and service from Senator Martin L. Davey from Ohio and The Davey Tree Expert Company. The famous tree lived happily for over another half century before being taken down in 2004.

Whether this tree was planted by George along with twelve others will probably never be conclusively proven. Were the people wrong to save the tree all those years ago without better evidence? Absolutely not. They saved a beautiful 200-year-old horse chestnut tree with a legendary attachment to George Washington, but they also saved a bit of their own past, nostalgia, and pride in their own town’s history.

Heather Baldus

Collections Manager