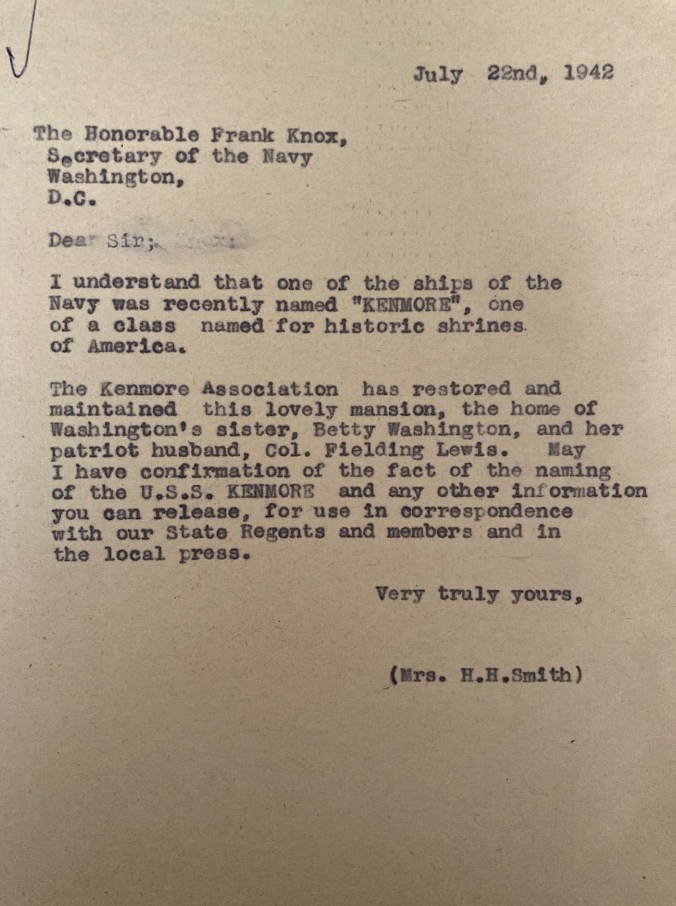

On July 22, 1942, Annie Fleming Smith wrote a letter. Smith was a prolific letter writer—her innumerable missives had helped raise the funds that saved Kenmore two decades earlier—so it is not surprising that she put pen to paper on that summer day. What is surprising is that the intended recipient of that letter was not a prospective donor, a fellow regent of the Kenmore Association, or a friend. Instead, she addressed her epistle to Frank Knox, the Secretary of the Navy. Smith wanted “confirmation of the fact of the naming of the U.S.S. KENMORE” after the home and “any other information you can release” about the ship.[1]

Although there is no record that Knox responded to Smith (there was, after all, a war on), the USS Kenmore was, in fact, named for the historic estate. The Naval History and Heritage Command ship-naming file on Kenmore I (AP-62) includes an April 13, 1942, memo to the Secretary of the Navy from the chief of the Bureau of Navigation and prepared by Louis Emil Denfeld, then assistant chief of the Bureau of Navigation, recommending that the President Madison be renamed Kenmore, in honor of the “[h]ome of Betty Washington at Fredericksburg, Virginia, sister of George Washington who married Col Fielding Lewis.”[2] The recommendation was approved on April 16 of that year, and the newly renamed vessel was “commissioned at Baltimore, Md., on 5 August 1942, Cmdr. Myron T. Richardson in command.”[3]

Smith had learned of the ship during a mid-1942 visit to the estate from Lt. Commander William VanC. Brandt (USNR) of the Kenmore, who later wrote to “Miss Annie” to thank her for her hospitality.[4] “All the Officers of the Kenmore,” Brandt told Smith, “were most interested in learning the history and record of the beautiful estate for which our ship is named.”[5] Brandt planned to have framed and displayed in the ship’s wardroom photographs of the property given to him by Smith; later, the vessel’s captain requested a picture of the house for his room.[6] For her part, Smith was “thrilled” to meet Brandt and “to know about your ship,” although she was skeptical enough of the origin of the transport’s new name to write Knox.[7]

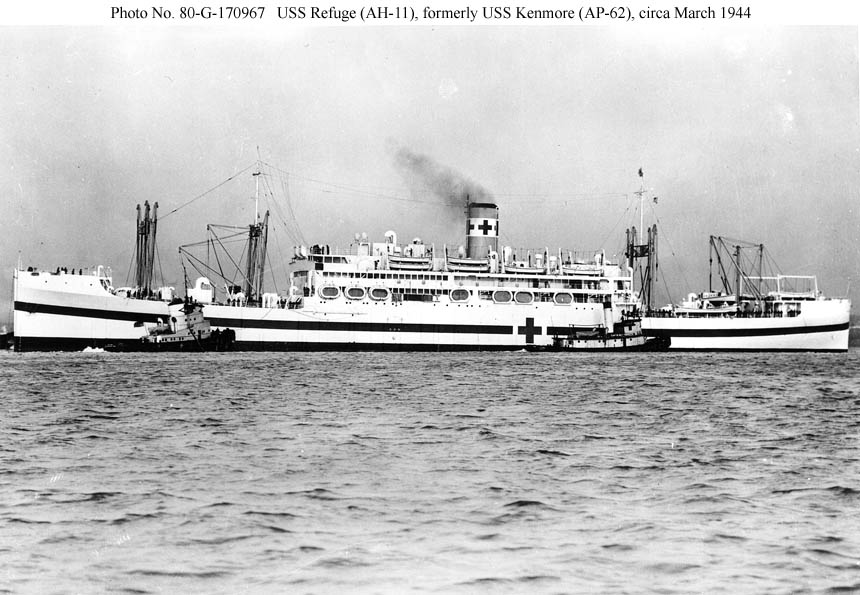

The Kenmore operated primarily in the Pacific until September 1943; she was then converted into a hospital ship and renamed Refuge.[8] The Navy must have liked the name Kenmore, as it was bestowed in October 1943 on another transport, originally called the James H. McClintock.[9] The Kenmore II also served in the Pacific Theater and, after “hostilities ended on 15 August 1945, [began] returning veterans to the U.S.”[10] She was decommissioned on February 1, 1946.[11]

The Kenmores were not the only vessels named for properties associated with George Washington and his family. The Wakefield (AP-21) borrowed its name from the Westmoreland County birthplace of the first president, today owned by the National Park Service.[12] There have been five Mount Vernons; the first was built in 1859 and chartered by the Navy two years later, before they bought it later that year.[13] The most recent vessel named after Washington’s residence and plantation was a dock landing ship commissioned in 1972 and decommissioned in 2003.[14] The possible birthplace of Mary Ball, George Washington’s mother, lent its name to the Epping Forest, a dock landing ship launched in 1943.[15]

The monikers of other ships are connected more tenuously to places tied to George Washington and his family. For example, a 1943 submarine chaser was rechristened the Abingdon in 1956.[16] The vessel’s new name came from the town of Abingdon, in Washington County, Virginia (named, yes, for George Washington).[17] According to the county’s official history, “myths claim that [the town] was named for Martha Washington’s ancestral home” in England.[18] While this may be a false etymology, were those who named the ship drawing on the tale when they chose to call the vessel Abingdon? Additionally, the many Arlingtons that have served the Navy over the years have each been named after Arlington County, which draws its appellation from Arlington House, built for George Washington Parke Custis, the step-grandson of his celebrated namesake.[19]

The Navy’s infatuation with the commander in chief of the Continental Army has, of course, also been expressed by naming ships directly after Washington and his family, not just their properties. While a complete inventory of such vessels is beyond the scope of this post, it is worth noting that four ships have been named the George Washington, including CVN-73, an active nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, while several others have sailed under just his surname.[20] Martha, George’s wife and the nation’s first first lady, has inspired the names of at least two Navy ships: the Lady Washington and the Martha Washington.[21] Civilian shipbuilders have also found inspiration in the Washington family: the SS Mary Ball was a liberty ship active during World War II.[22]

Who was responsible for naming these ships? As hinted at above, while final authority for ship names was (and still is) the responsibility of the Secretary of the Navy, during World War II, it was the Bureau of Navigation (renamed the Bureau of Personnel on May 21, 1942) that researched and recommend ship names based on the traditional naming conventions associated with each class of vessels.[23]

Typically, it was dock landing ships, or LSDs, that were named for “cities and places of historical interest of same name, or places of historical interest only.” [24] Epping Forest, Gunston Hall I (named for George Mason’s home), Ashland (for the boyhood home of Henry Clay), Carter Hall (after the Virginia estate), Oak Hill (for the home of President James Monroe), and Shadwell (for the birthplace of Thomas Jefferson) are all examples of LSDs whose names aligned with this convention.[25]

But the Kenmores, the Mount Vernon IV, and the Wakefield were not LSDs; they were transports, classified AP, and anyone seeking consistency in the Navy’s naming of troop transports during World War II is bound to be disappointed. Some vessels in the AP class were named after celestial bodies, others after Revolutionary War heroes, and others, as we have seen, after historic estates.

This lack of consistency is not surprising. After all, when Benjamin Stoddert named the Navy’s sixth ship, a frigate, he chose to call it the Chesapeake, despite President George Washington’s agreement with the recommendation that frigates be named after “principles or symbols found in the US Constitution.” Therefore, “the very first naming decision by the very first Secretary of the Navy resulted in the ‘corruption’ of the established naming convention.”[26] This tradition of flexibility regarding ship names has endured, and ship names continue to excite interest (and occasionally strong feelings) from many parties, including those who propose denominations for new vessels. If you are such a person, here’s an idea: how about another Kenmore, or maybe a Ferry Farm?

Adam Nubbe

Manager of School & Youth Programs

[1] Smith, Annie Fleming to Frank Knox, July 22, 1942. The George Washington Foundation.

[2] Naval History and Heritage Command, Kenmore I, ship-naming file, April 13, 1942.

[3] Ibid; Cressman, R. J. (2020, March 31). Kenmore I (AP-62). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/k/kenmore.html

[4] Brandt, William VanC. to Annie Fleming Smith, June 30, 1942. The George Washington Foundation.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid; Smith, Annie Fleming to William VanC. Brandt, July 10, 1942. The George Washington Foundation.

[7] Smith, Annie Fleming to William VanC. Brandt, July 10, 1942. The George Washington Foundation.

[8] Naval History and Heritage Command, Kenmore I, ship-naming file, April 13, 1942.

[9] Cressman, R. J. (2020, March 31). Kenmore II (AP-162). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/k/kenmore-ii–ap-162-.html

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Cressman, R. J. (2022, April 1). Wakefield (AP-21). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/w/wakefield.html

[13] Naval History and Heritage Command. (2015, August 11). Mount Vernon I (Gbt). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/m/mount-vernon-i.html

[14] Pike, J. (n.d.). LSD 39 Mount Vernon. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/navy/lsd-39.htm

[15] Naval History and Heritage Command. (2015, July 8). Epping Forest. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/e/epping-forest.html

[16] Mann, R. A., & Cressman, R. J. (2023, November 27). Abingdon (PC-1237). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/a/abingdon.html

[17] Ibid; Hagy, J. W. (2019, June 10). A Brief History of Washington County, Virginia. Washington County, Virginia. https://www.washcova.com/history/

[18] Ibid.

[19] Parsons, L., & Cressman, R. J. (2023, December 13). Arlington I (AP-174). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/a/arlington-i.html; Arlington, Virginia. (n.d.). History of Arlington. https://www.arlingtonva.us/Government/Topics/Welcome-Kit/History-of-Arlington; National Park Service. (2023, January 12). George Washington Parke Custis. https://www.nps.gov/arho/learn/historyculture/george-custis.htm

[20] Naval History and Heritage Command. (2020, May 5). Washington VIII (BB-56). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/w/washington-viii.html; US Navy. (n.d.). USS George Washington (CVN 73). https://www.airpac.navy.mil/Organization/USS-George-Washington-CVN-73/

[21] Naval History and Heritage Command. (2016, February 9). Martha Washington. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/m/martha-washington.html; Naval History and Heritage Command. (2015, July 28). Lady Washington. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/l/lady-washington.html

[22] Jobrack, J. (2020, September 10). True or False? Test Your Knowledge of Mary Washington. https://livesandlegaciesblog.org/2020/09/10/true-or-false-test-your-knowledge-of-mary-washington/.

[23] Calkins, W. F. (1958, July). Down to the sea in ships’–names. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1958/july/down-sea-ships-names; Naval History and Heritage Command. (2020, June 29). Denfeld, Louis Emil. Louis Emil Denfeld. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/research-guides/modern-biographical-files-ndl/modern-bios-d/denfeld-louis-emil.html

[24] Department of the Navy, A Report on Policies and Practices of the U.S. Navy for Naming the Vessels of the Navy (2012, November), 63. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA569699.pdf

[25] DANFS – Naval History and Heritage Command. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships — Index. (n.d.). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs.html

[26] Department of the Navy, A Report on Policies and Practices of the U.S. Navy for Naming the Vessels of the Navy (2012, November), 7. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA569699.pdf